Ukraine has largely weathered Russia’s power grid attacks — but is bracing for more

- Share via

KYIV REGION, Ukraine — In a blustery, knife-edge wind on the banks of the Dnipro River, a burly Ukrainian army major — who aptly goes by the military call sign Bison — guffawed at the notion that cold and tedium presented a hardship for air defense crews guarding against incoming Russian drones and missiles.

“Twenty-four hours of sitting in the snow and waiting — that beats an hour under shelling anytime!” said the 35-year-old officer, who oversees a battery of vehicle-mounted Stinger missiles about 25 miles outside the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

With the war’s southern and eastern front lines largely frozen during winter months, matching the frigid weather, Ukrainian forces have turned much of their focus to protecting civilian infrastructure in densely populated urban areas.

Since October, stepped-up Russian airborne attacks on Kyiv and other cities have smashed apartment blocks and hospitals, bus stops and power substations across the country, seriously disrupting the electricity supply in Kyiv and elsewhere.

But Bison and the seven air defense crews he commands are feeling optimistic. Nearly a year into the fighting, the Russian attempt to smash the national power grid, depriving Ukrainians of light and heat in the dark winter months, appears to have largely failed.

In Kyiv, a city of 3 million people, the wail of air-raid sirens still sounds several times most days whenever a missile-armed fighter jet takes off from a base in Russia or Belarus. There was an alert during Monday’s surprise visit by President Biden as he and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky strolled outside a downtown landmark monastery.

A widely used cellphone app voiced by “Star Wars” actor Mark Hamill provides the all-clear when an alert is lifted, with Hamill intoning in his Luke Skywalker voice: “May the Force be with you.”

President Biden delivered a forceful speech Tuesday in Poland ahead of the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Whole swaths of Kyiv were plunged into darkness earlier in the winter, but now, the lights are back on. Cafes and coffeehouses are warm and welcoming. Some previously darkened monuments are again spotlighted against the chilly sky, and streetlights turned off to save power are being put into service again.

Remote workers who for months haunted metro stations and flocked to “invincibility points” offering hot tea and power chargers rarely have to resort these days to finding an alternative workspace equipped with lights and electricity.

“Before, they’d come every day — there was a line to get a place on the couches,” said Valentina, a 59-year-old employee at a big-box chain store called Epicenter, with several branches around Kyiv.

During the worst of the wintertime outages, she said, people showed up with work laptops and other devices, plopping themselves onto comfy armchairs in the furniture display, plugging in power strips and giving their restive children the run of the kids’ furniture section.

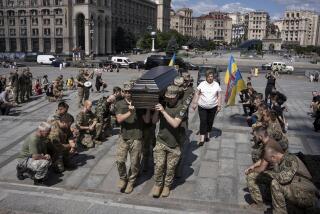

Los Angeles Times photographers document the battle in Ukraine after Russian forces invaded nearly a year ago.

But that wartime twist on remote work tailed off in January as the frequency of missile attacks dropped and repair crews, often working around the clock, managed to counter much of the destruction wrought by missiles and drones.

An infusion of foreign-donated generators and transformers has helped as well, and the government has announced that two previously deactivated nuclear power stations are feeding into the national grid once again, easing the strain.

As winter first set in, the threat of Ukraine going dark appeared dire. In October, when Russia embarked on the first of at least 14 withering wave-style airborne attacks, self-exploding drones struck a symbolic blow, hitting the headquarters of the national power company, Ukrenergo. Its chief, Volodymyr Kudrytskyi, watched an explosion wreck the top two floors of the building.

Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko even warned that if the city’s power grid collapsed and water and sewage consequently failed, the capital might have to be evacuated.

Now, for the most part, only towns and villages closest to the front lines suffer from a continuing lack of electricity — and even in such places, beleaguered residents are apt to point out that the relatively mild winter is nearly over, and they’ve managed.

But peril still awaits. The capital and the air defense crews guarding it are bracing themselves for the prospect of an onslaught coinciding with Friday’s anniversary of the invasion’s start — particularly because an attempted Russian offensive in Ukraine’s east appears to be faltering.

Western military analysts say Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently hoped for some significant battlefield victory to trumpet before the anniversary, such as seizing the contested town of Bakhmut. That has not happened, despite a horrific casualty count as waves of Russian troops, some of them prisoners recruited by the mercenary Wagner Group, are mowed down in attacks on Ukrainian positions. Ukrainian forces have also suffered heavy losses in the fighting around Bakhmut.

The longest battle of the war in Ukraine has turned Bakhmut into a ghost city fought over by Ukrainian troops and by Russian forces eager for a win.

Out on Kyiv’s air defense perimeter, the shoot-down rate of Russian missiles and drones is high, although the Stinger operators are keenly aware that even a few getting through the net can have bloody and destructive consequences.

U.S. military aid, including a $500-million package announced by Biden this week, contains a substantial share devoted to air defense. Military analysts credit Ukraine with a nimble strategy of keeping such defenses dispersed and mobile.

As an icy sleet began to fall, a two-man missile crew on a Stinger dual-launch vehicle outside Kyiv showed the forest redoubt where they shelter between trips to launch sites out in the open when a Russian attack is in progress.

Russia routinely fires dozens of missiles and drones almost simultaneously, seeking to overwhelm Ukrainian defenses. The two-man crew from Ukraine’s 1129th Antiaircraft Missile Regiment demonstrated how they scramble to fit the Stingers into place on the vehicle’s tripod and expertly adjust the scopes — and, after firing, just as rapidly move to break down their gear so they can head back to cover.

War wounds and traumatic captivity, cherry liqueur and air-raid alerts: Weathering the year-old Russian invasion

During an actual assault, that adrenaline-charged interlude tends to feel both long and short.

“I don’t even really have anxiety anymore. I kind of got used to it,” said the crew’s 25-year-old “shooter,” a private whose name was withheld in accordance with Ukrainian military policy. “It was harder at first.”

Asked what it’s like to miss a target, he sighed deeply. Success, on the other hand, feels like a personal triumph, making him think of friends and family under attack in Kyiv at that moment.

“I feel like when I hit the target, I’ve saved someone’s life,” he said. “I’m defending my country.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.