Alabama plans to carry out first nitrogen gas execution. How will it work and what are the risks?

- Share via

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Alabama is preparing to use a new method of execution: nitrogen gas.

Kenneth Eugene Smith, who survived the state’s previous attempt to put him to death by lethal injection in 2022, is scheduled to be put to death Thursday by nitrogen hypoxia. If carried out, it would the first new method of execution since lethal injection was introduced in 1982.

The state maintains that nitrogen gas will cause unconsciousness quickly, but critics have likened the never-used method of execution to human experimentation.

What is nitrogen hypoxia?

Nitrogen hypoxia execution would cause death by forcing the inmate to breathe pure nitrogen, depriving him or her of the oxygen needed to maintain bodily functions.

Has it ever been used?

No state has used nitrogen hypoxia to carry out a death sentence. In 2018, Alabama became the third state — along with Oklahoma and Mississippi — to authorize the use of nitrogen gas to execute prisoners.

Some states are looking for new ways to execute inmates because the drugs used in lethal injections, the most common execution method in the United States, are increasingly difficult to find.

How is it supposed to work?

Nitrogen, a colorless, odorless gas, makes up 78% of the air inhaled by humans and is harmless when breathed with proper levels of oxygen.

The theory behind nitrogen hypoxia is that changing the composition of the air to 100% nitrogen will cause an inmate to lose consciousness and then die from lack of oxygen.

Much of what is recorded in medical journals about death from nitrogen exposure comes from industrial accidents — where nitrogen leaks or mix-ups have killed workers — and suicide attempts.

What does the state plan to do?

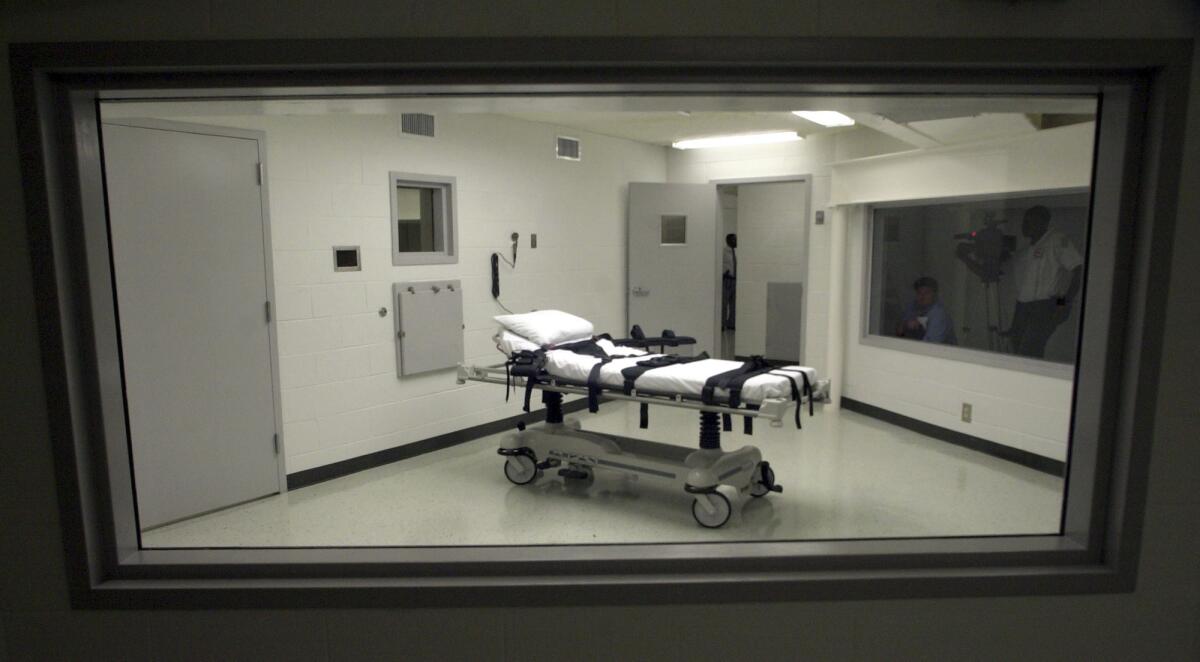

After Smith is strapped to the gurney in the execution chamber, the state said in a court filing that it will place a “Type-C full facepiece supplied air respirator” — a type of mask typically used in industrial settings to deliver life-preserving oxygen — over Smith’s face.

The warden will then read the death warrant and ask Smith if he has any last words before activating “the nitrogen hypoxia system” from another room. The nitrogen gas will be administered for at least 15 minutes or “five minutes following a flatline indication on the EKG, whichever is longer,” according to the state protocol.

The state heavily redacted sections of the protocol related to the storage and testing of the gas system.

The Alabama attorney general’s office told a federal judge that the nitrogen gas will “cause unconsciousness within seconds, and cause death within minutes.”

What are the criticisms?

Smith’s attorneys say the state is seeking to make him the “test subject” for a novel execution method.

They have argued that the mask the state plans to use is not airtight and oxygen seeping in could subject him to a prolonged execution, possibly leaving him in a vegetative state instead of killing him. A doctor testified on behalf of Smith that the low-oxygen environment could cause nausea, leaving Smith to choke to death on his own vomit.

Experts appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council earlier this month cautioned that, in their view, the execution method would violate the prohibition on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment.

The American Veterinary Medical Assn. wrote in 2020 euthanasia guidelines that nitrogen hypoxia can be an acceptable method of euthanasia under certain conditions for pigs but not for other mammals because it creates an “anoxic environment that is distressing for some species.”

Is this the same as a gas chamber?

Not exactly. Some states previously used hydrogen cyanide gas, a lethal gas, for executions. The last prisoner to be executed in a U.S. gas chamber was Walter LaGrand, the second of two German brothers sentenced to death for killing a bank manager in 1982 in southern Arizona. It took LaGrand 18 minutes to die in 1999.

Who is the inmate?

Smith was one of two men convicted of the 1988 murder-for-hire of a preacher’s wife. Prosecutors said Smith and the other man were each paid $1,000 to kill Elizabeth Sennett on behalf of her husband, who was deeply in debt and wanted to collect insurance money.

Alabama attempted to execute Smith in 2022 by lethal injection. He was strapped to the gurney in the execution chamber being prepared for lethal injection, but the state called off the lethal injection when execution team members had difficulty connecting the second of two required intravenous lines to Smith’s veins. Smith was strapped to the gurney for nearly four hours, according to his lawyers, as he waited to see if the execution would go forward.

Are there legal challenges?

The question of whether the execution can proceed will end up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments Friday in Smith’s request to block the execution. After the court rules, either side could appeal.

Smith has argued that the state’s proposed procedures violate the ban on cruel and unusual punishment. He has also argued that Alabama violated his due process rights by scheduling the execution when he has pending appeals and that the face mask will interfere with is ability to pray.

In a separate case, Smith is arguing it would violate the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment for the state to make a second attempt to execute him after he already survived one execution attempt. Lawyers for Smith on Friday asked the U.S. Supreme Court to stay the execution to consider that question.

What is potentially at stake?

Lethal injection is the most commonly used execution method in the United States, but death penalty states have struggled at times to obtain the needed drugs or encountered other problems in connecting intravenous lines.

If the Alabama execution goes forward, other states may seek to start to using nitrogen gas.

If the execution is blocked by the court or botched, it could halt or slow the pursuit of nitrogen gas as an alternative execution method.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.