Supreme Court Justices Barrett and Sotomayor, ideological opposites, unite to promote civility

- Share via

WASHINGTON — With the Supreme Court’s approval hovering near record lows, two justices have teamed up to promote the art of disagreeing without being nasty about it.

In joint appearances less than three weeks apart, Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Sonia Sotomayor, ideological opposites, said the need for civil debate has never been greater than it is in these polarized times. And they said the Supreme Court, where voices don’t get raised in anger, can be a model for the rest of the country.

“I don’t think any of us has a ‘my way or the highway’ attitude,” said Barrett, who is promoting compromise from a position of strength as part of the high court’s super-majority of conservative justices. She spoke Tuesday at a conference of civics educators in Washington.

Sotomayor, speaking at a meeting of the nation’s governors in late February, said the justices’ pens can be sharp but also deft in writing opinions. “There are so many, many things that you can do to bring the temperature down and to have you functioning together as a group to getting something done that has a benefit in the law,” she said.

Confidence in the Supreme Court sank to its lowest point in at least 50 years in 2022, after the Dobbs decision that overturned the right to abortion.

Oddly enough, Barrett used strikingly similar language to criticize Sotomayor and the other two liberal justices less than two weeks ago.

The nine justices unanimously rejected state efforts to kick Republican former President Trump off 2024 ballots over his efforts to undo his election loss to Democrat Joe Biden four years ago. But the three liberals criticized the court for going too far.

“We cannot join an opinion that decides momentous and difficult issues unnecessarily, and we, therefore, concur only in the judgment,” Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson, Elena Kagan and Sotomayor wrote in a joint opinion.

Barrett basically agreed with them. But she didn’t like the tone.

“In my judgment, this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency. The Court has settled a politically charged issue in the volatile season of a Presidential election,” Barrett wrote. “Particularly in this circumstance, writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.”

Congress could impose ethics rules on the Supreme Court without violating the Constitution, but enforcing them is another matter.

Barrett is rarely in dissent on a court that, relatively soon after she joined, overturned abortion rights, curbed Biden administration environmental efforts, broadened religious rights, expanded gun rights and ended affirmative action in college admissions.

At 52, Barrett is the youngest member of the court. She was appointed by Trump, joining the court a little more than a month after the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Barrett’s election year confirmation by a Republican-controlled Senate infuriated Democrats. Barrett was Trump’s third high-court appointee. Four years earlier, Senate Republicans blocked President Obama’s Supreme Court nomination of Merrick Garland, now President Biden’s attorney general, explaining that the vacancy should await the outcome of the 2016 election, eventually won by Trump.

Sotomayor, 69, has been on the court since 2009, appointed by Obama. She has written tough dissents from the decisions on affirmative action and abortion, jointly with the other liberal justices in the latter. During arguments in the abortion case, Sotomayor bitterly criticized her conservative colleagues. “Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts? I don’t see how it is possible,” she said nearly seven months before the court overturned Roe.

Confidence in the court fell to its lowest level in 50 years following the abortion decision in June 2022, and polling done just before the court began its new term in October found little change.

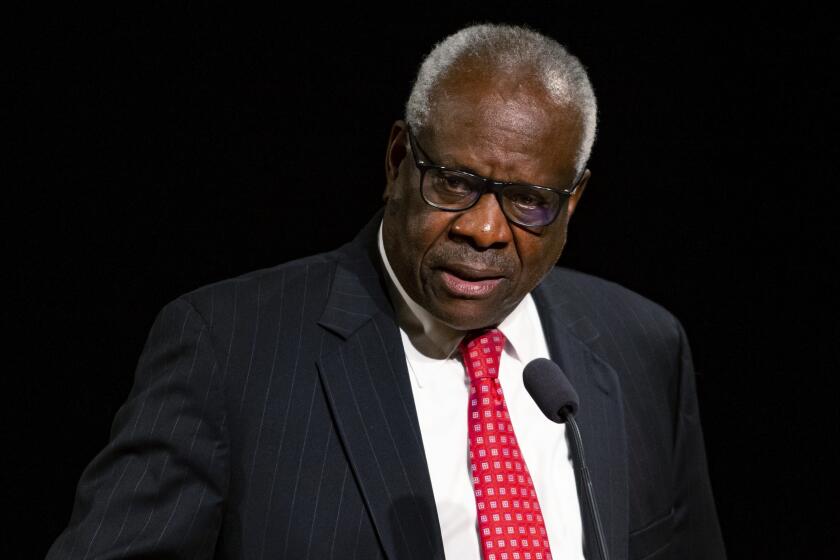

Chief Justice Roberts says the ethics rules depend on the justices using ‘good judgment.’ Thomas is testing that theory.

The justices’ appearances hark back to the traveling road show conservative Antonin Scalia and liberal Stephen G. Breyer put on 15 or so years ago. But Breyer and Scalia cheerfully debated their different approaches to the law. Barrett and Sotomayor acknowledge they see things differently but instead focus on their determination to disagree civilly. Sotomayor serves on the governing board of iCivics, an education nonprofit started by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

“We do not interrupt one another, and we never raise voices,” Barrett said at the civics conference, describing the justices’ private meetings at which they talk about the cases they’ve just heard.

Justices speaking publicly about the court’s collegiality is nothing new. But something unusual happened after the abortion decision. Some justices engaged in a public back-and-forth over the court’s legitimacy, the very topic Sotomayor raised in the courtroom.

Kagan began the exchange by saying that the court risks losing its legitimacy if it is perceived as political. She returned to the theme last summer at a Portland, Ore., appearance in which she emphasized “the importance of courts looking like they’re doing law, rather than willy-nilly imposing their own preferences as the composition of the court changes.”

Justice Clarence Thomas’ luxury travels put pressure on the court to adopt new ethics rules. But the new code looks like the existing one for federal judges.

Kagan’s comments followed a term in which the conservatives were united in the affirmative action decision and in scrapping Biden’s $400-billion plan to cancel or reduce federal student debt loans and issuing a major ruling that affects gay rights.

But there were other major cases in which conservative and liberal justices joined to reject aggressive legal arguments from the right, including on Native American rights, immigration and elections.

The court that was partially remade by Trump will undoubtedly remain an issue this election year. Major decisions await on abortion, guns, the power of federal regulators and whether Trump can be prosecuted on charges he interfered with the 2020 election.

Most of those rulings will come down in June, as the justices race to finish their work and feelings sometimes get rubbed raw, even without any shouting.

Sherman and Whitehurst write for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.