Rwanda’s leader is concerned about perceived U.S. ambiguity about victims of the 1994 genocide

- Share via

KIGALI, Rwanda — Rwandan President Paul Kagame said Monday he was concerned by what he saw as a U.S. failure to characterize the 1994 massacres as a genocide against the country’s minority Tutsis.

Kagame told reporters that the issue was an “element of discussion” in talks with former U.S. President Clinton, who led the American delegation to a ceremony Sunday commemorating the 30th anniversary of the genocide in which Hutu extremists slaughtered about 800,000 people, most of them Tutsis, in a government-orchestrated campaign.

Many Rwandans criticized U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken for failing to specify that the genocide targeted the Tutsis when he wrote late Sunday: “We mourn the many thousands of Tutsis, Hutus, Twas, and others whose lives were lost during 100 days of unspeakable violence.”

Responding to a journalist’s question about Blinken’s post on the social platform X, Kagame said he believed he had reached an agreement with U.S. authorities a decade ago for them not to voice any criticism on the genocide anniversary.

“Give us that day,” he said, adding that criticism over “everything we are thought not to have at all” is unwanted on the genocide anniversary.

Rwandan authorities insist any ambiguity on who the genocide victims were is an attempt to distort history and disrespects the memory of the victims.

U.S. officials did not comment on Monday. President Biden issued a statement Sunday, saying, “We will never forget the horrors of those 100 days, the pain and loss suffered by the people of Rwanda, or the shared humanity that connects us all, which hate can never overcome.”

Rwandan President Paul Kagame has blamed the inaction of the international community for allowing the 1994 genocide to happen.

“In the 100 days that followed, more than 800,000 women, men, and children were murdered. Most were ethnic Tutsis; some were Hutus and Twa people. It was a methodical mass extermination, turning neighbor against neighbor, and decades later, its repercussions are still felt across Rwanda and around the world,” Biden wrote.

“We honor the victims who died senselessly and the survivors who courageously rebuilt their lives. And we commend all Rwandans who have contributed to reconciliation and justice efforts, striving to help their nation bind its wounds, heal its trauma, and build a foundation of peace and unity. Those efforts continue to this day.”

The question of how to memorialize the genocide stems from allegations that the Rwandan Patriotic Front — the rebel group that stopped the massacres and has ruled Rwanda unchallenged since 1994 — carried out its own revenge killings during and after the genocide.

Kagame has previously said that his forces showed restraint. He said in a speech Sunday that Rwandans are disgusted by what he described as the hypocrisy of Western nations that failed to stop the genocide.

The genocide was ignited when a plane carrying then-President Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down over Kigali on April 6, 1994. The Tutsis were blamed for downing the plane and killing the president, and became targets in massacres led by Hutu extremists that lasted over 100 days. Some moderate Hutus who tried to protect members of the Tutsi minority were also killed.

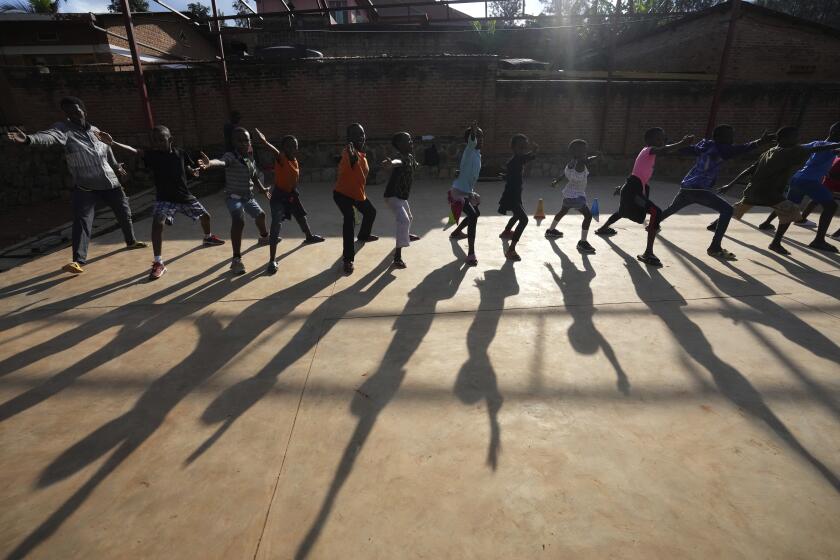

As part of weeklong commemorations, flags flew at half-staff and public places across Rwanda were told to keep entertainment quiet.

Mass graves are still being found in Rwanda, 30 years after the genocide in which extremist Hutus killed an estimated 800,000 Tutsis in the Central African country.

Rwandan authorities also face questions over how to present commemoration activities in a way that acknowledges the efforts of some Hutus to protect their Tutsi neighbors.

“You see, those who are denying the genocide are saying, ’Ah, to commemorate? It’s a big serious barrier to unity. We have to move forward, to forget about commemoration,’” said Naphtal Ahishakiye, executive secretary of a prominent group of genocide survivors in Kigali. “Those are wrong. They have genocide ideology. They don’t want to remember what happened.”

The government has long blamed the international community for ignoring warnings about the killings, and some Western leaders have expressed regret.

French President Emmanuel Macron said last week that France and its allies could have stopped the genocide but lacked the will to do so. Macron’s declaration came three years after he acknowledged the “overwhelming responsibility” of France — Rwanda’s closest European ally in 1994 — for failing to stop Rwanda’s slide into the slaughter.

Although Kagame is a U.S. ally and has friendly relations with many Western leaders, he is under growing pressure over Rwanda’s military involvement in eastern Congo, where tensions have flared recently as the two countries’ leaders accuse one another of supporting armed groups. In February, the U.S. urged Rwanda to withdrawal its troops and missile systems from eastern Congo, for the first time describing the M23 as a Rwanda-backed rebel group.

Twenty-five years ago, Tasian Nkundiye murdered his neighbor with a machete.

U.N. experts have said they had “solid evidence” that members of Rwanda’s armed forces were conducting operations there in support of M23, whose rebellion has caused the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people in Congo’s North Kivu’s province.

Kagame said Monday that the M23 are fighting for the rights of Congolese Tutsis, with at least 100,000 of them now seeking shelter in Rwanda after fleeing attacks in eastern Congo.

Rwandan authorities say they want to deter rebels, including Hutu extremists responsible for the genocide, who fled to eastern Congo.

Rwanda’s ethnic composition remains largely unchanged since 1994, with a Hutu majority. The Tutsis account for 14% and the Twa just 1% of Rwanda’s 14 million people.

Kagame’s Tutsi-dominated government has outlawed any form of organization along ethnic lines, as part of efforts to build a uniform Rwandan identity. National ID cards no longer identify citizens by ethnic group, and authorities imposed a tough penal code to prosecute those suspected of denying the genocide or the “ideology” behind it.

But some observers say the law has been used to silence critics who question the government’s policies, including how to build lasting unity and reconciliation.

Muhumuza and SSuuna write for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.