India’s Modi is not known for leading by collaboration. After lackluster election result, he may have to adapt

- Share via

NEW DELHI — Since coming to power a decade ago, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been known for aggressive and often snap decisions that he has found easy to execute thanks to the majority he enjoyed in India’s lower house of parliament.

In 2016, he yanked more than 80% of bank notes from circulation in an effort to curb tax evasion that devastated citizens who lost money. In 2019, his government pushed through a controversial law that stripped the special status of Muslim-majority Kashmir, a disputed territory, with hardly any debate in parliament. In 2020, Modi brought in contentious agriculture reforms — though he was forced to drop those about a year later after mass protests from farmers.

In his expected next term as prime minister — when he will need a coalition to govern after election results announced Wednesday showed that his Hindu nationalist party fell short of a majority — Modi may have to adapt to a leadership style with which he has little experience.

“Negotiating and forming a coalition, working with coalition partners, grappling with the trade-offs that come with coalition politics — none of this fits in well with Modi’s brand of assertive and go-it-alonepolitics,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute.

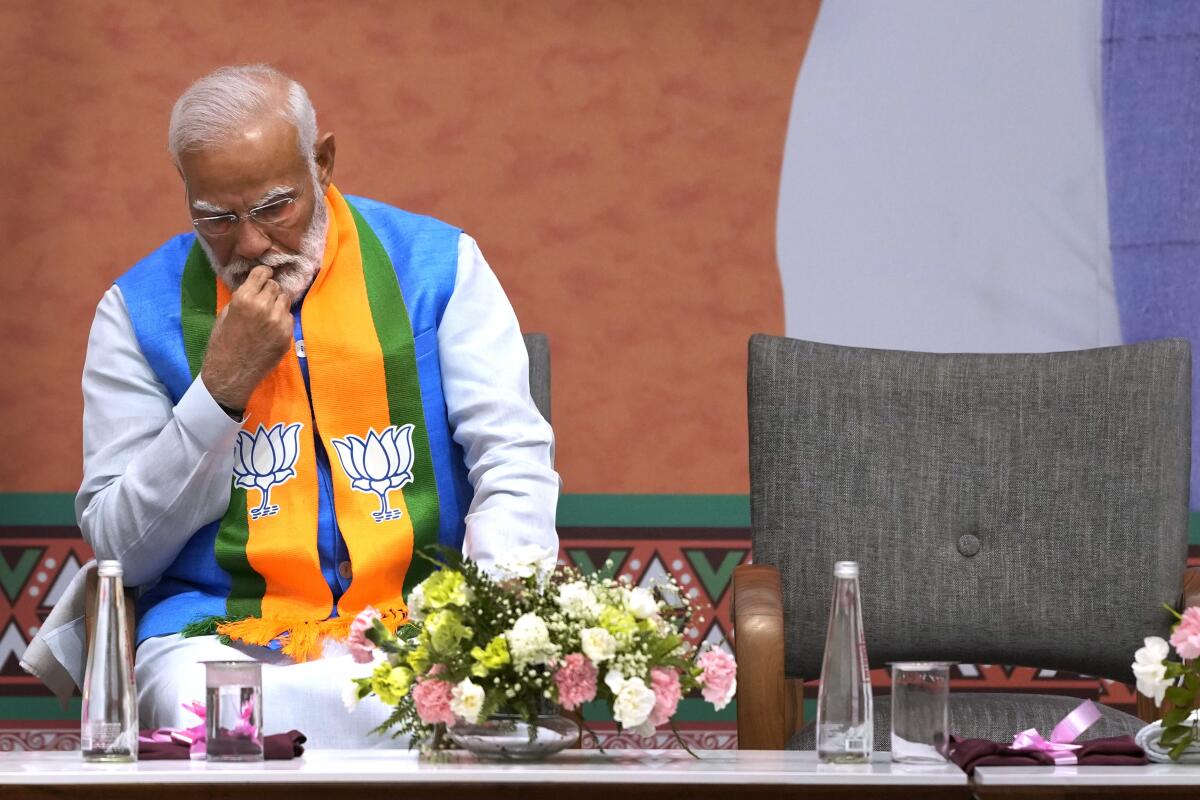

Prime Minister Narendra Modi claimed victory for his alliance in India’s general election, despite a lackluster performance from his own party.

The election results upended expectations of a stronger showing for Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. The party ended up winning 240 seats — short of the 272 needed to form the government on its own.

But the coalition to which the party belongs, the National Democratic Alliance, secured a majority in the 543-seat lower house that should allow Modi to retain power in the world’s most populous nation.

“India cuts Modi down,” read one newspaper headline Wednesday, referring to the 642 million voters and the opposing INDIA alliance, which clawed seats away from the BJP.

This is a major setback for Modi, who has not needed his coalition partners to govern since becoming prime minister in 2014. It has left him in the most vulnerable position of his 23-year career.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government is implementing a citizenship law that excludes migrants who are Muslim.

“These results show that the Modi wave has receded, revealing a level of electoral vulnerability that many could not have foreseen,” Kugelman said.

India has a history of messy coalition governments — but Modi, who has enjoyed astronomical popularity, offered a respite, leading his BJP to landslide victories in the last two elections. His supporters credit him with transforming the country into an emerging global power, with a robust economy that’s No. 5 in the world.

That economy, however, is in some trouble — and fixing it will require partners. Modi’s opponents focused on vulnerabilities — such as unemployment, inflation and inequality — despite the brisk growth, but his campaign offered few clues to how he might address those issues.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, one of India’s most beloved and polarizing political leaders, has advanced the cause of Hindu nationalism.

“Modi hardly addressed the question of unemployment — they skirted around it,” said Yamini Aiyar, a public policy scholar.

It’s not just that Modi will have to adapt to relying on a coalition. The election has also left him diminished after he spent a decade building a persona of absolute invincibility, said Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

At the heart of his governance style has been his penchant for control, critics say, adding that Modi has increasingly centralized power.

But to stay in power, Modi will have to do whatever he can to maintain a stable coalition, meaning he will probably have to govern in a way that is more collaborative because the smaller regional parties in his alliance could make or break his government.

The BJP’s lackluster performance is “undoubtedly a slap in the face,” Vaishnav said.

Modi confidently predicted at his first election rally, in February, that the party would secure at least 370 seats — 130 more than it did.

The gap between the high expectations for the BJP and its actual performance has left the victors looking like losers and the defeated feeling victorious.

However, Vaishnav said, “we shouldn’t lose sight that the BJP is still in the driver’s seat.”

To be sure, Modi’s most consequential Hindu nationalist policies and actions are locked in — including a controversial citizenship law and the Hindu temple he had built atop a razed mosque. His critics say his actions have bred intolerance and stoked tensions against the country’s Muslim community — and left India’s democracy faltering, with dissent silenced and the media under pressure.

Now, his agenda could face fiercer challenges, especially from a once deflated but resurgent opposition.

The INDIA alliance, led by the Congress party, will probably have more power to apply pressure and push back, especially in parliament, where its numbers will grow.

“Modi is Modi. But I would say that with the attitude with which he ran the country until now, he will definitely face some problems now,” said Anand Mohan Singh, 45, a businessman in New Delhi. “Some changes will be visible.”

Pathi writes for the Associated Press. AP video journalist Shonal Ganguly contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.