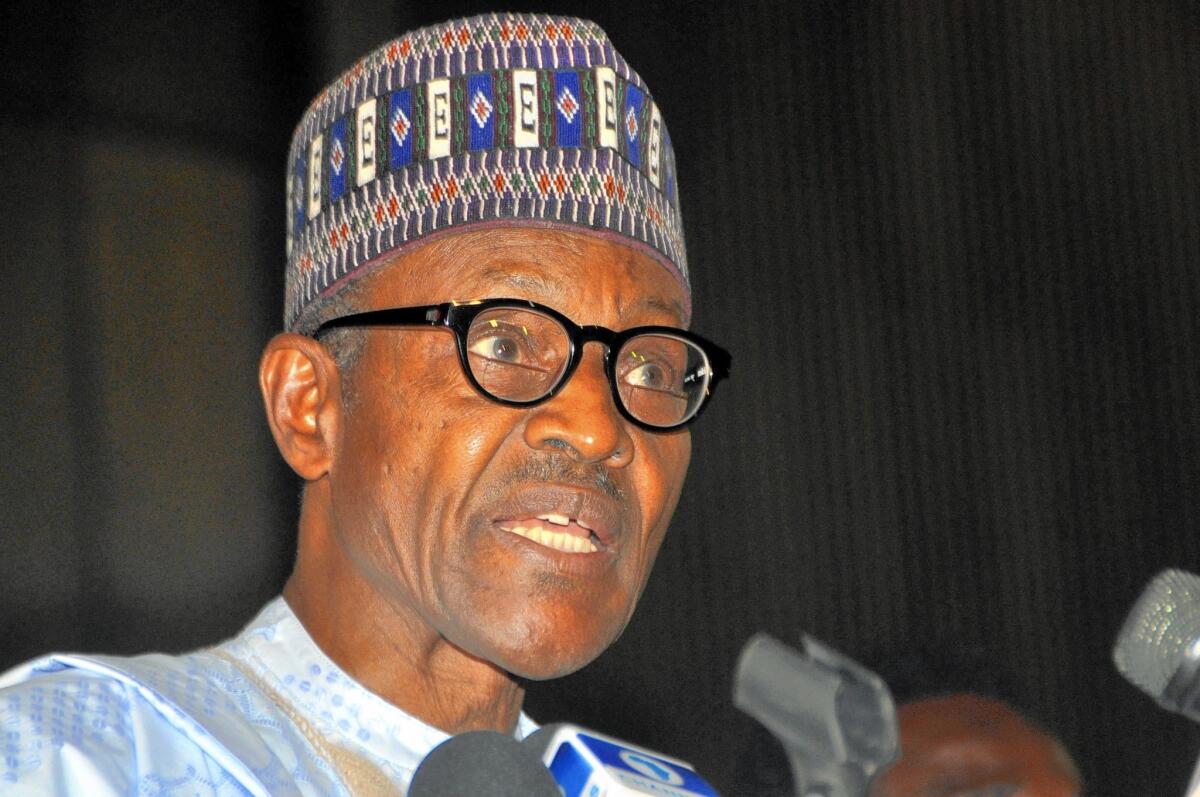

Nigeria president-elect’s stern side now an asset, not a liability

- Share via

Reporting from Kano, Nigeria — Muhammadu Buhari, a former military ruler who jailed journalists, critics and one of Nigeria’s most famous musicians, Fela Kuti, seems an unlikely figure to rise 30 years later as the country’s savior.

Dour, austere, introspective, and defeated in three previous attempts to be president, Buhari has promised Nigerians that he’s now a democrat who has come a long way since he was ousted as a military dictator in 1985.

But ironically, it is Buhari’s stern, forbidding side that many Nigerians now admire, after decades of corruption and five years in which the nation drifted under President Goodluck Jonathan’s affable but ineffectual rule.

Nigerians continued wild celebrations Wednesday. Many wore thick, old-fashioned Buhari-style glasses, painted themselves all over in the national colors of green and white, waved brooms and carried coffins to symbolize Jonathan’s political demise.

In 1983 Buhari ousted a democratically elected government, accusing it of corruption. He was soon overthrown himself after his controversial crackdown on critics, jailing of journalists and bans on strikes and demonstrations. The deeply unpopular charges against the beloved king of Afro Beat, Kuti, were politically motivated, Amnesty International said at the time.

Although there’s some alarm in parts of the south about his autocratic past, played up furiously by Jonathan’s campaign team, Buhari’s uncompromising stance on corruption and his promise to take a tough stand on the militant group Boko Haram still make him attractive to many.

Buhari hammered at those two themes Wednesday in his first televised address as president-elect.

“Boko Haram will soon know the strength of our collective will. We should spare no effort until we defeat terrorism,” he said. He also vowed to fight corruption, saying it undermined democracy and made some people unjustly rich. “Corruption will not be tolerated by this government.”

“A leader with his reputation for anticorruption will be a huge benefit to Nigeria,” Clement Nwankwo, an analyst with an Abuja-based think tank, the Policy and Legal Advocacy Center, said in an interview. “We hope he will be able to bring his own officials to account, and where there’s been obvious cases of corruption, he will be able to prosecute people who abused public trust in terms of their financial duties.”

He said there was lingering anxiety about Buhari’s autocratic past, but Nigeria’s vibrant civil society, its vocal Twitterati and human rights organizations would protest if Buhari tried arresting critics.

“Given his record, people will be very watchful, monitoring closely his powers,” Nwankwo said. “Civil society is a lot stronger than it was then. This is not military rule. This is civilian constitutional rule. This is democracy.”

Buhari is in good health for a 72-year-old, goes for a daily run and neither drinks nor smokes. He is an old-fashioned leader who hews to tradition. In a series of photos with his wife and family designed to soften his image, he nonetheless looked stiff, formal and uncomfortable.

But the reason he personified hope for many Nigerians, said Patrick Smith, editor of the authoritative journal Africa Confidential, was that his ascetic, strict persona stood in stark contrast to Jonathan’s.

The administration of Jonathan, the first president from the southeast, was all about favors and contracts for the “home boys” from his region, Smith said.

“I think this is one of the more promising aspects to [Buhari’s] government. He’s more than anything a nationalist. I don’t think he’s going to say all the contracts are going to Katsina,” said Smith, referring to Buhari’s home state. “He’s not going to let these people run all over him.”

Buhari inherits a colossal mess: a violent insurgency that shows no sign of going away soon; a shell of an army, with a deeply corrupt officer corps and demoralized, poorly trained foot soldiers; an economy concentrated on oil and gas, with agriculture and manufacturing in decline.

Infrastructure has been neglected for years, and many households get sporadic electricity and buy water from carts in the street. Most serious of all, the price of oil, which accounts for 80% of government revenue, has been halved.

Buhari, who will take office at the end of May, has set up policy task forces to tackle the problems swiftly and is likely to launch a purge of corrupt military officials, Smith said.

The incoming government will expose the dire state of government finances, blame the previous government and impose tough medicine, Smith predicted. A key long-term plan, which Nigerians have grappled with unsuccessfully for decades, involves diversifying the economy to reduce dependence on gas and oil.

“He’s got this massive block vote in the north and he’s going to use that political capital to push through a lot of change. He’s going to push the whole ascetic leader aspect. It’s going to be about ethics in government, honesty in public service, both the political and civil services, the financial industry and particularly the oil and gas sector,” Smith said “It’s going to be a question of how much those moral values play in modern Nigeria.”

As with all new leaders, however, there’ll be pragmatism about who gets targeted. Powerful figures in his party, accused of corruption, are likely to be unscathed.

J. Peter Pham, director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center, said the collapse in government revenue would curb Buhari’s ability to invest in needed infrastructure and economic development.

“He has to live up to the very high expectations of Nigerians who believe in the change he promised and represented. People are going to be impatient. They will expect returns immediately,” Pham said.

Buhari previously had run for president under two political parties. He pulled off victory this time when opposition parties united in 2013, formed an alliance of the country’s populous north and large parts of the southwest, for the first time creating a party strong enough to oust an incumbent government in place since military rule ended in 1999.

Buhari won support in both the north and southwest, but the charged election rhetoric was divisive in a country delicately balanced between a mainly Muslim north and predominantly Christian south.

Jonathan’s strongest showing was in predominantly Christian areas, but it was not nearly enough. His organizers failed to get the vote out in his southern and southeastern strongholds, whereas Buhari inspired a massive turnout in the north. The final tally showed Buhari winning 55% to Jonathan’s 45% nationally.

Nigeria’s historic democratic transfer of power is a powerful symbol on a continent where it’s more common for presidents to change constitutional limits to extend their terms in office. Few African nations have seen democratic transfers, including Zambia, Malawi, Ghana, Senegal and Liberia. Last year, Burkinabe President Blaise Compaore was forced from office by riots after he tried to extend his term.

But Nigeria, a sprawling, seemingly chaotic nation of 170 million, fraught with sectarian tension and dogged by a history of violent, disputed polls, didn’t appear to be the prime candidate to emerge as Africa’s leading democratic light.

Already Africa’s most populous country by far, it has surpassed South Africa as the sub-Sahara’s largest economy. Now Nigeria has burnished its democratic credentials as well, passing the most important test: a peaceful transfer from one government to another, a trial South African democracy never faced because the governing party of the late Nelson Mandela hasn’t faced a strong challenge.

“Nigeria is Africa’s largest democracy and it’s also a country where the existing government has been very entrenched and powerful. To have an incumbent government voted out sends a very positive signal across the continent, that people can vote out a government they they’re dissatisfied with,” said Nwankwo, the analyst.

“I think it will be more difficult for long-serving African leaders to tamper with their terms, and to seek to entrench themselves in power beyond their constitutional limits,” he said.

Pham said Nigeria’s democratic transfer would have positive consequences across the continent. “It will be harder for smaller countries … to argue that this can’t be done in Africa,” he said.

“It takes the wind out of the naysayers who argue why they can’t do this, when Nigeria, which has far greater challenges, could do it.”

Times staff writer Carol J. Williams in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.