Fela Kuti built his music around a distrust of Nigeria’s elites. Now they’re the audience for the musical about his life

- Share via

Reporting from LAGOS, Nigeria — It’s a humid Thursday evening at one of the most exclusive hotels in Lagos, and police are everywhere. They check drinks at every entrance, supervise metal detectors and patrol the lobby in bulletproof vests while hundreds of wealthy Lagosians and expats sip overpriced cocktails and munch on fancified street food.

Security is always tight at private events in this city of 22 million, but the cops’ presence feels especially strange because the guests who paid $15 to $160 to be at the Eko Hotel are there to see a bare-bones version of a Broadway show celebrating the life and music of a singer who built his reputation on his fervent hatred of the Nigerian elite and the police who protect them.

“Them dey break, yes, them dey steal, yes, them dey loot, yes,” Fela Kuti sang about the police and military, before he died of AIDS in 1997. “Them dey rape, yes, them dey burn, yes, them dey burn.”

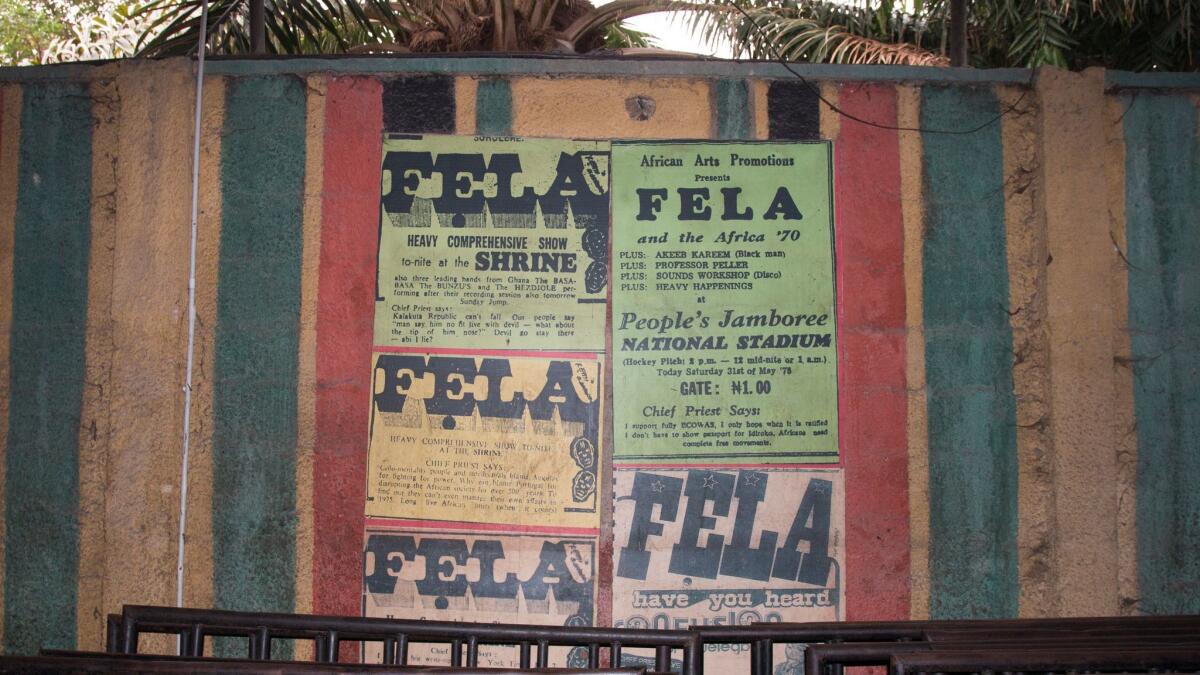

Across town, Kuti’s son, Femi, was preparing for his weekly public rehearsal at his family’s legendary concert hall, the Shrine, where entrance is free most nights of the week, cold beers are $1.50, and a joint doesn’t cost much more.

The contradiction of these two coinciding events underscores some of the inherent challenges of reproducing a Broadway show in the city where it’s set. That’s especially true in Lagos, the West African megacity defined by its vast income inequality, a theme central to much of Fela Kuti’s music.

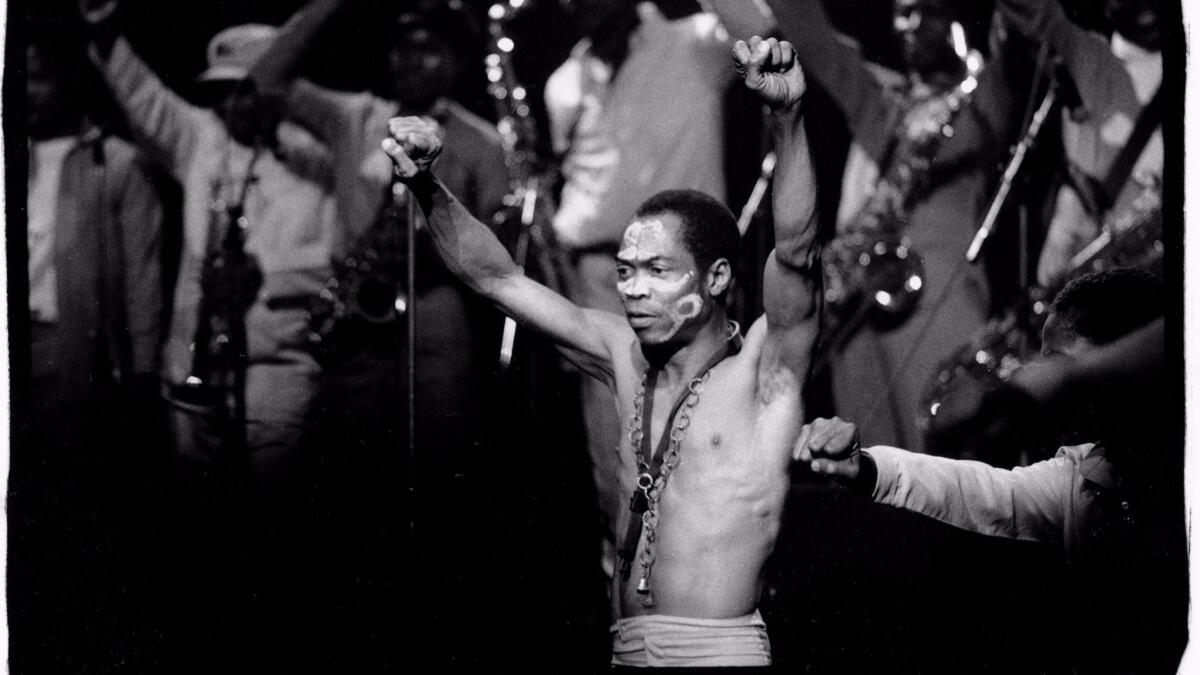

Kuti was known worldwide as the king of Afrobeat. He produced about 50 albums of politically conscious music that enraged the Nigerian government and defended universal struggles of the working class, earning himself comparisons to Bob Marley.

The musical “Fela!” premiered off-Broadway in New York in 2008 and moved to Broadway the following year. Since its debut, more than a million people have seen the production across the United States and England, and it has racked up three Tony Awards. The show chronicles Kuti’s difficult life, features his original music and offers audiences a lens into his rise to fame, which led to his violent encounters with police and soldiers who targeted him for his political lyrics.

When you present this play in New York or in London, it’s a story. In Lagos, it’s history.

— Rikki Stein, Kuti’s longtime manager and friend

When Kuti’s son, Femi, a famous musician in his own right, first heard about the show celebrating his father, he claimed he would only watch it in New York if the producers promised it would later come to Nigeria. “When I finally saw it, I cried like a baby,” Kuti said. “I wasn’t ready. They took my mind back.”

And the production team kept its side of the promise, bringing “Fela!” home for the first time in 2011 and the second time last month. But there’s a discord between the somewhat glamorous story of Fela’s ascent and the way a musical celebrating him had to be packaged when it was brought to his hometown.

“When you present this play in New York or in London, it’s a story,” said Rikki Stein, Kuti’s longtime manager and friend, who served as executive producer for “Fela!” “In Lagos, it’s history.”

To Nigerians, Kuti was much more than a singer. He was one of the country’s first musicians who tried to use his fame as a force for good. His lyrics criticized the Nigerian government for corruption and human rights abuses, and Kuti paid the price: He was arrested about 200 times, and his mother died from injuries she sustained during a military raid on their home. At one point, soldiers assigned to stop his performances burned down the original Shrine.

None of that slowed Kuti down. He even tried to run for president. “He proclaimed that his first act upon being elected would be to enroll the entire population in the police force,” Stein wrote in Kuti’s obituary. “Then, he said, ‘Before a policeman could slap you, he would have to think twice because you’re a policeman, too.’” (Unsurprisingly, Nigerian officials barred him from participating in the election.)

Even two decades after his death, Kuti’s music is played and replayed across the country, and his lyrics remain ever relevant to Nigerians’ daily lives.

Lagos is the most populous city in Africa, and Nigeria’s massive oil industry has created a visible wealth gap here. Decades-old waterfront slums now sit in the shadows of high-rise condominiums, and there’s so much demand for luxury apartments that developers are building man-made islands to create more space to accommodate them. The cost of living in the city’s most expensive areas is comparable to Los Angeles or New York.

In the poorer areas, deep in the heart of mainland Lagos, where Kuti’s son Femi lives, electricity will go out for weeks at a time. And an unemployment crisis has prompted so many Nigerians to leave the country that they accounted for 10% of all migrants and refugees who crossed the Mediterranean during 2016, according to the United Nations.

Despite Nigeria’s class struggle, time has changed Kuti’s legacy here, allowing the very people he criticized to come to appreciate his music and his movement. “Fela! The Concert” ran for four nights in Lagos in April, and while it may have been marketed to a higher-income bracket, its goal was to continue to share and celebrate Kuti’s life and impact in Nigeria.

Kuti earned his fame while the country was ruled by a military dictatorship. It has since transitioned to a fledgling democracy, and while corruption and abuse of power remain rampant, Kuti’s international recognition and the passage of time have softened his reputation. Once seen solely as a maker of protest music, now he is embraced with pride by mainstream Nigerian culture.

In the latest rendition of the musical, the producers dropped much of the original storyline to create a stripped-down show of Kuti’s most famous hits. The downsizing was largely a logistical decision, Stein said. When the musical cast visited Lagos in 2011, it took 40 tons of equipment, five trucks and 94 people just to unload and install the set. Despite the adjustments, the most recent show didn’t disappoint: It was complete with a 10-piece Afrobeat band, a troupe of dancers, and of course, Kuti himself, played by American actor Sahr Ngaujah.

On opening night, Kuti’s fans flooded excitedly into an air-conditioned concert hall at the hotel, and those in the front rows were soon on their feet. Many of the attendees who dished out for tickets are not regulars at the Shrine, where Femi Kuti still plays twice a week. Still, the younger Kuti understands his father’s reach, and has become more open to remembrances that honor him in different settings.

“Everyone loved him because his touched everyone’s pain,” Kuti said of his father. “Plumber, carpenter, driver, house help — everybody understood him.”

Ola Abidakun, a local government official who paid $75 for his seats to the show at the Eko Hotel was drawn to it in part because it wasn’t a Nigerian production. “When I heard it was performed by non-Nigerians, non-Africans, even, I thought, ‘That’s amazing,’” he said. “‘I just have to see it.’”

Abidakun’s comments run contrary to what Femi described as the most common criticism his father’s friends and fans have expressed over the original show. When talk first emerged about the American interpretation of Kuti’s stories, many people believed it should have been produced and cast by Nigerians. But Femi came to disagree with that sentiment, and now sees the benefits of showcasing it with an international hook. The level of dramatic and musical training needed to make the show work couldn’t have happened without the support available on Broadway, he said.

In 2011, at Femi’s request, the “Fela!” cast performed one show for a jam-packed crowd at the Shrine, and tickets were only a few bucks a pop. But the sheer cost of moving a massive performance abroad means that just to break even, the tickets can’t always be so affordable. After that opening night, the show moved to the Eko Hotel, where it also lived for the entirety of its return to Lagos last month. On that first night at the hotel in April, the audience called for encore after encore.

“Fela’s life deserves to be global,” Femi said. “He deserves for everyone to understand Nigeria and the political climate, what was happening in his mind and what his struggles were.”

ALSO

With 20 million people facing starvation, Trump’s foreign aid cuts strike fear

O’Grady is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.