Threatened by the Taliban, some schools in Pakistan close -- others arm teachers and build walls

A Pakistani police officer stands guard as children make their way to school in Lahore, Pakistan, on Monday.

- Share via

reporting from Peshawar, Pakistan — In the aftermath of a deadly attack on a Pakistani university, many private schools across the country remain closed, and others have implemented heavy security to guard against the threat of further violence.

By Monday, at least 12 chains of private schools had not reopened institutions in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and other provinces that had been closed following the Jan. 20 raid by militants on a private university in Charsadda, in northwest Pakistan.

In the capital, Islamabad, which has been spared the worst of the militant attacks of recent years, parent Ilyas Khan said he received a text message late Sunday night saying the private school where his two children are enrolled would remain closed until further notice.

A Pakistani Elite Police Force member takes part in a drill to fight against militants at a school in Peshawar on Thursday.

Millions of parents have experienced the same uncertainty since four attackers stormed Bacha Khan University in Charsadda and killed 21 people, most of them students. Umar Mansoor, a commander of the outlawed Pakistani Taliban militant organization, claimed responsibility for the attack in a video message and warned it was the start of a fresh offensive.

Describing universities such as Bacha Khan — named for a pacifist leader of the resistance to British colonial rule — as bastions of secular education, Mansoor said his fighters would target law schools and other institutions that trained Pakistan’s military officers, politicians, judges and other officials. The Pakistani Taliban has been waging a long-running insurgency to replace the secular government in Islamabad with a system based on Islamic law.

This still image taken from a video released by a Pakistani Taliban faction on Jan. 22 shows its leader Umar Mansoor, center, delivering a statement from an undisclosed location.

“After consultation, we have decided to target schools, colleges and universities to eliminate the basis of this infidel system and establish supremacy and sovereignty of Allah in this country,” Mansoor said in a video message.

His message — coming a year after the Pakistani Taliban killed nearly 150 people, most of them children, at an army-run school — has exacerbated a security crisis in Pakistan’s education system.

As soft targets, schools have faced the brunt of rising militant violence here over the last decade. More people have died in attacks on schools in Pakistan than in any other country since the 1970s, according to the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database.

Public schools in some provinces were open Monday, but mostly private, English-language schools in Peshawar, 20 miles from Charsadda, informed parents Sunday night that they would remain closed indefinitely.

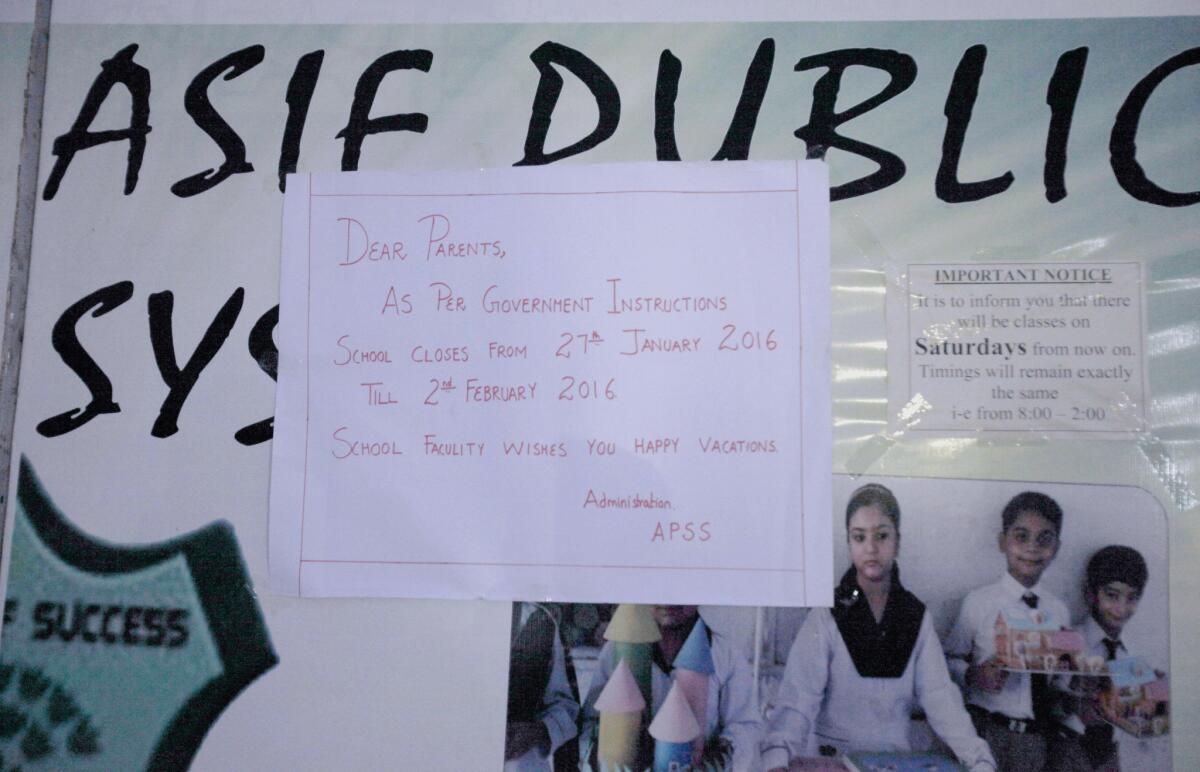

A notice about a school closing hangs on the main gate of a private facility in Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, which includes Peshawar and Charsadda, the provincial government has spent more than $76 million on security measures at 28,000 public schools, including building new boundary walls and reconstructing damaged buildings.

Pakistani authorities have ordered private schools to increase their security measures, noting that there aren’t enough military and police personnel to protect every campus. Pakistan’s home ministry said it was preparing new security guidelines; authorities in some provinces have already closed dozens of private schools for failing to upgrade security following the December 2014 attack at the army-run school.

Some provincial governments have issued licenses to teachers and security guards to carry light weapons. Guards wielding assault rifles have been deployed on top of some school buildings.

In Peshawar, armed police have been deployed at the entrance of the city’s main higher education institution, the University of Peshawar, which has more than 60,000 students. The campus has taken on the look of a military garrison, with watchtowers set up atop buildings, new closed-circuit television cameras, raised boundary walls and additional security personnel.

Pakistani activists from the Awami Workers Party shout slogans during a protest in Karachi on Jan. 22 after a militant attack on a university.

Khwaja Yawar Naseer, who owns a private school in Peshawar, said that following orders from officials, he “installed five CCTV cameras, four security guards, a watchtower on the top floor of the two-story building and raised the height of the boundary wall to 10 feet.”

But Naseer wondered if even those measures were sufficient given the increasingly brazen attacks launched by militants against even the most heavily fortified targets.

“When terrorists can enter the general headquarters of the Pakistani Army in Rawalpindi, attack the naval dockyard in Karachi and air force installations, then they can target any place at will,” Naseer said.

Students attend an assembly at a government primary school in Peshawar, Pakistan, on Jan. 21.

He blamed the government for creating fear and uncertainty among children and their parents.

“Terrorists wanted to close education institutions, so they have succeeded in their mission,” Naseer said. “The government should not create fear by closing schools and universities.”

Ali is a special correspondent. Staff writer Shashank Bengali contributed to this report from Mumbai, India.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.