Once banned, the facial tattoo reappears as a cultural asset and political weapon in Taiwan

- Share via

Reporting from Xincheng Township, Taiwan — As a child, Kimi Sibal got his first lesson on the significance and the stigma of the facial tattoo when he asked his grandmother about the strange markings on her face.

Facial tattoos had been banned in Taiwan by Japanese colonists decades earlier and his grandmother hushed him, worried that if the wrong person saw the black vertical lines across her forehead she might be beaten or tossed in prison.

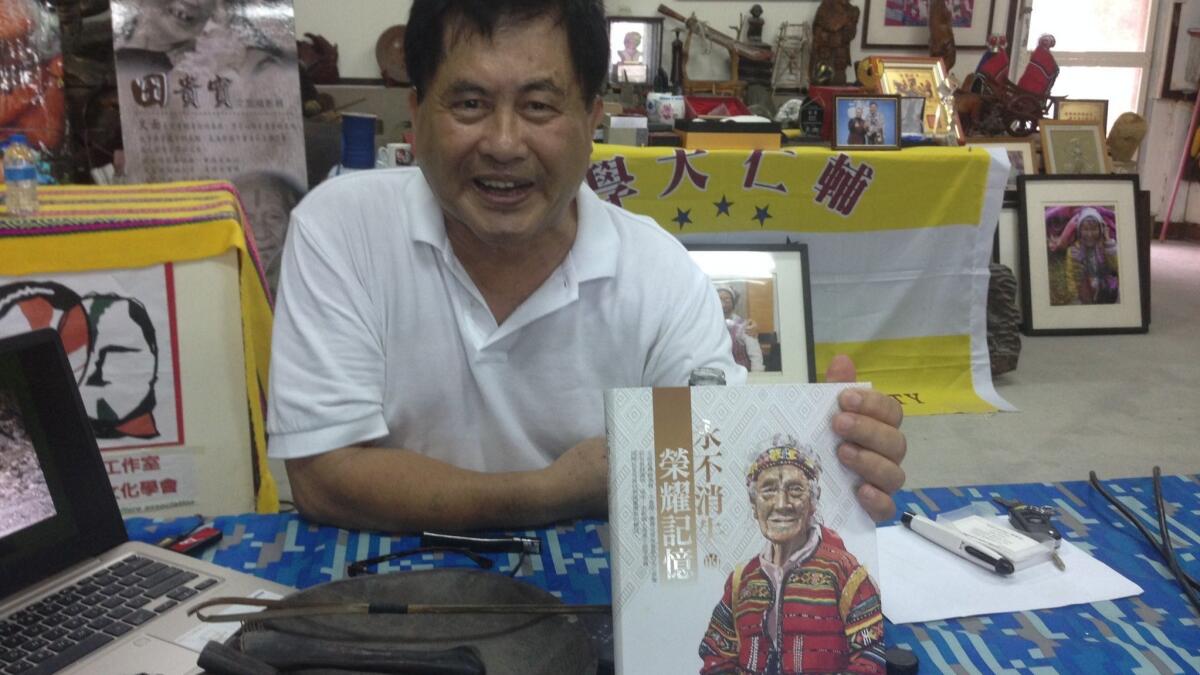

Although the long-ago colonists saw the tattoos as a form of mutilation, Sibal and others came to recognize them as vivid reminders of Taiwan’s aboriginal culture, something to preserve — if only in photographs. Now, as part of a larger movement to save the customs, languages and artifacts of Taiwan’s past, Sibal has collected hundreds of photographs of older Taiwanese who bear the tattoos.

“I really just want everyone to understand our culture, why we had tattoos, Sibal said. “And I don’t want them to think we’re savages.”

Preservation suddenly matters in Taiwan as residents here try to reach into their past to distinguish themselves from China, a political rival that cites ethnic bonds as a reason to unify the island and the massive country. Polls show Taiwanese strongly favor autonomy from China.

Sibal, 66, is an indigenous Taiwanese man who lives in the island’s steep mountains that his Truku tribe has always called home. The Truku people and those in at least two other tribes on the island of Taiwan once tattooed their faces, withstanding pain so intense they couldn’t open their mouths for days, to prove themselves worthy hunters or weavers who deserved to join other tribe members in the afterlife. Those not tattooed risked being expelled from the villages.

Compared with the intricate designs of the modern-day tattoo, the artwork of the facial tattoos in Taiwan was simple, though impossible to miss — a black stripe across the forehead to indicate an achievement or a profession, a thicker band extending from the mouth to each ear, a sign of beauty,

Government officials believe there are now only two people left on the island who have the original facial tattoos. Through the years, though, Sibal has photographed about 300 people with the markings and collected around 100 stories to go with the images. Portraits of elderly tattooed women cover every wall of his home-based exhibition hall, where he lectures to tourists and students.

It’s vital work, says Tony Coolidge, an American national who is half indigenous and runs the Taiwan-based advocacy group Atayal Organization, which works to preserve indigenous culture.

“That’s something that’s unique for all of Taiwan,” he said. “It’s iconic. You can say the indigenous culture is all the Taiwanese have to set themselves apart from the Chinese culture.”

Most Taiwanese trace their lineage to China, and Beijing cites that heritage as part of its claim that China and Taiwan, ruled separately since the 1940s, belong under one flag. The relationship between the two has so grown so fractious that China has even asked international airlines to stop referring to Taiwan as a country.

Indigenous people have populated Taiwan for about 3,500 years, but they now number just half a million people, or 2% of Taiwan’s population. Still, interest in the island’s past has grown.

Taiwan’s central government has allocated money since 2012 to preserve native languages and aboriginal culture. The budget was tripled this year to about $20 million, and last year, parliament ordered the government to establish a foundation to develop writing systems and dictionaries for indigenous languages.

The effort is focused on saving nine languages that are disappearing, said Luo Mei-chin, a specialist in the government’s Council of Indigenous Peoples’ education and culture office. While elders still use the old languages, their children generally speak Chinese, especially those who move from tribal villages to the cities.

The government is now paying instructors to teach the languages to their students in one-on-one or two-on-one sessions.

Striped and multicolored ceremonial clothing, dances, and wood carvings of totem-like shapes have returned to public view over the last decade, and there are now 29 small-scale museums in Taiwan that display indigenous artifacts such a tools and early-day canoes. Tourism has helped fuel interest in the items.

The surge in preserving Taiwan’s past has helped restore the lost pride of the facial tattoo.

The tattoos date back more than 1,000 years, but the Japanese banned them during their colonization of Taiwan from 1895 to 1945, people in China viewed them as the markings of a criminal. In dynastic China, ex-convicts would be given facial tattoos to brand them for life. And even modern-day Taiwanese have long associated the tattoos with the island’s organized crime gangs.

But the government council now recognizes the tattoos as “artifacts,” said Luo Mei-chin. Recently, Taiwan’s culture minister praised the two remaining people with facial tattoos “for maintaining the unique cultural tradition,” according to the ministry’s website.

One of those is 95-year-old Ke Ju-lan, who recalled the social pressure to get tattooed when she turned 15. “If you don’t get a tattoo, people can’t tell whether you’re from the Atayal tribe or a plains person,” said Ke, an Atayal tribe member in the northwestern county of Miaoli.

Before the ban, indigenous people would get face tattoos as early as 5. Women would display a striped black line from a soot-based solution etched into the skin from their ears to their mouths as a sign of beauty.

“I did not look forward to the day because I was young at the time,” said Ke, whose tattoo is on her forehead and cheeks. “It was so painful that my whole face was swollen. I was supposed to get tattooed twice, but the man who tattooed me left and the Japanese confiscated the tools.”

Sibal began to photograph the tattoos when he was a young father, usually squeezing in photo shoots after long hours at the factory where he worked and using his own money for equipment and film. Sometimes, he said, he would get resistance when he went to neighboring villages, asking to take picture of the tattoos.

“They’d even sic their dogs on me,” he said. To get access and photo opportunities, he would bribe neighboring villagers with fruit, money and alcohol.

A collection of his photographs along with the stories of many of those who were tattooed was published last year.

“You need to remember your traditions and not let people scold you,” said Sibal. “That’s the essence.”

Jennings is a special correspondent

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.