Crime wave, police complicity batter Mexico’s Jalisco state and trigger angry protests

- Share via

Reporting from Guadalajara, Mexico — A surge in gang killings, kidnappings and other crimes is gripping central Mexico’s Jalisco state and sparking street protests in a region famed for some of the country’s singular cultural emblems — from mariachi music to tequila to Mexican-style rodeo.

And, in a disturbing but familiar scenario in Mexico, corrupt lawmen in the service of criminal gangs appear to be complicit in the escalating violence.

Recent high-profile cases in Jalisco include the disappearance of three film students, the seizure of three Italian citizens and the kidnapping and execution of a pair of Mexican federal agents from an elite squad targeting organized crime.

Police have been implicated in two of the incidents, and prosecutors are investigating reports that police were behind the students’ disappearance — the case that sent multitudes of protesters into the streets here last week and unleashed a social media campaign from colleagues, relatives and others, including Oscar-winning director Guillermo del Toro, a native tapatío, as Guadalajara residents are known.

Armed men who identified themselves as police seized the three students on March 19 on a street in the Guadalajara suburb of Tonala and drove off with the young men in a pair of SUVs, according to witness accounts.

“We demand that authorities return my son and his two companions,” Sofia Avalos, mother of one of the students, Marco Avalos, 20, told reporters on March 22. “We demand that he and his two colleagues be returned alive. [We] want them back. We need them back. We love them.”

State authorities have launched a search for the vanished students — and also are seeking a fourth student who went missing the same day in a separate incident — but have not commented on possible police involvement in their seizures. Officials have offered an award of 1 million pesos — about $55,000 — for information on the whereabouts of the four students.

Lawmakers have hastened to provide reassurance to edgy Jalisco residents, while pointedly offering no guarantees that the wave of violence will end anytime soon.

“Difficult days are coming, I won’t lie to you,” Jalisco Gov. Aristoteles Sandoval warned citizens earlier this month, while vowing to send more police cruisers and uniformed officers to embattled police departments. “The situation is critical, and there is no indication that it is getting better.”

The governor spoke March 7, a day after six bodies were found in an abandoned vehicle parked not far from the center of Guadalajara, the state capital.

Violence has long formed a significant undercurrent of life in Jalisco, which stretches from the Mexican interior to the Pacific coast and is home to about 8 million people, mostly concentrated in the Guadalajara metropolitan zone. Jalisco, especially the coastal Puerto Vallarta area, also hosts a major tourist industry and permanent foreign population, including many U.S. retirees and vacation homeowners. The state is also a longtime source of immigrants to the United States.

Guadalajara was the base of the former cartel that notoriously kidnapped and killed undercover U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena in 1985. Under intense pressure from Washington at the time, Mexican authorities moved forcefully to break up the Guadalajara Cartel, which soon split into regional cartels that assumed drug-smuggling routes to the booming U.S. market.

But officials call the current violent upsurge the worst in recent memory.

“This is an epoch of horror,” Gov. Sandoval acknowledged. But, he declared, the criminals “cannot be stronger than us. They cannot intimidate us.”

There were 247 homicides recorded in Jalisco during the first two months of 2018, according to official figures. That’s a jump of almost 25% compared to the same period in 2017 — a year that set a new record for murders in the state and nationwide.

Human rights activists and others say disappearances also have surged to new highs in Jalisco, with more than 300 people reported missing already this year.

The state is now home turf to one of Mexico’s most brutal and fast-growing crime syndicates: the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, an offshoot of the Sinaloa Cartel once headed by Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, now jailed in New York after his extradition to the United States. New Generation is among a number of factions fighting for lucrative segments of El Chapo’s splintered criminal domain, resulting in periodic gangland slayings and shootouts.

A longtime trademark of Mexican mobs has been the practice of buying off or intimidating cops, prosecutors and judges. The gangs’ cash resources dwarf what officials can earn in public salaries.

“A lot of this is about economics,” said Darwin Franco, a journalist and academic in Guadalajara who has followed crime in the region. “Sometimes the local police have to cooperate [with cartels] because their bosses demand it.”

Also, thugs do not hesitate to kill police officers or anyone else infringing on their illicit trade.

Kidnappings and disappearances often serve as a “message” directed at rivals, authorities or the general public, Franco noted. Cops often do the dirty work. Throughout Mexico, police have been implicated in the disappearances of scores of people, many with no known link to criminal activity.

Police in the town of Tecalitlan in southern Jalisco have been accused in the Jan. 31 abduction of the three Italians, who, according to Italian relatives, were in Mexico selling imported electrical equipment. Officials say police handed the Italians over to a criminal organization, reportedly an affiliate of the New Generation band. The men have not been seen since. Their disappearance has led to street protests in their hometown of Naples, Italy. The motive for their abduction remains unclear.

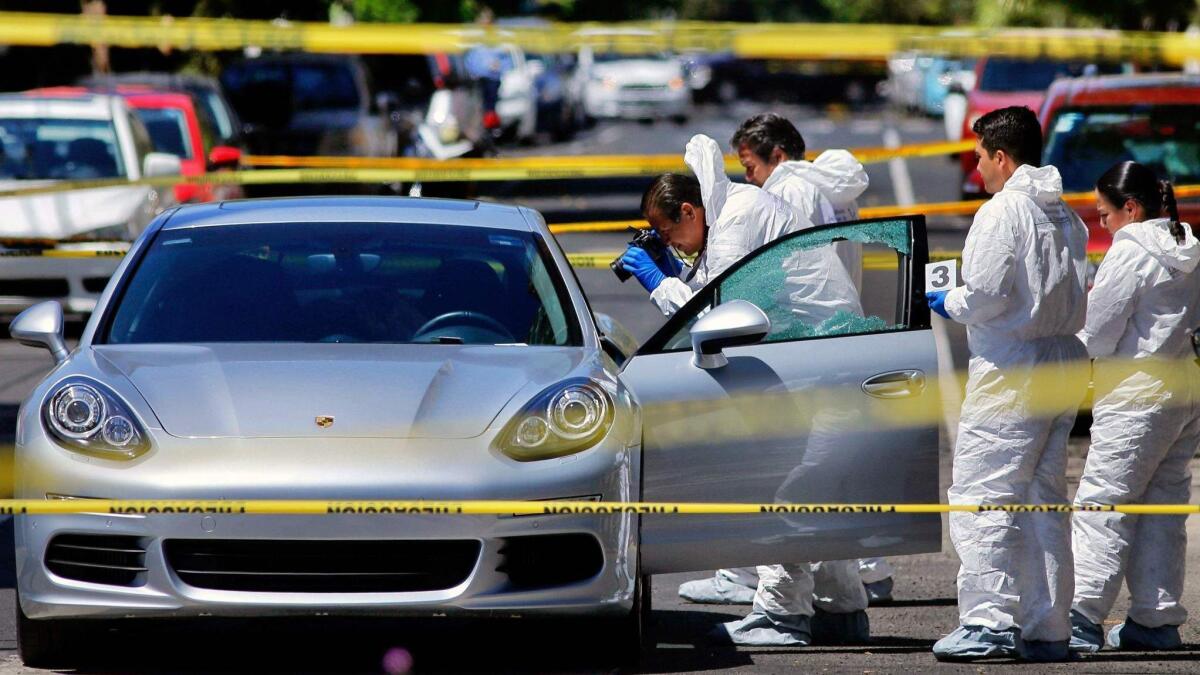

In Puerto Vallarta, two top municipal police commanders were among more than a dozen suspects arrested this month in the kidnapping and slaying of the two federal agents from an elite squad targeting organized crime. Their slayings were clearly meant as warning from the New Generation cartel to authorities, observers say.

The remains of the agents turned up in the neighboring Pacific Coast state of Nayarit days after the two captive agents appeared in a chilling, jihadist-style internet video making a clearly coerced anti-police declaration against an Islamic State-like backdrop of masked gunmen toting assault rifles.

Things have gotten so out of hand in the sprawling Guadalajara suburb of San Pedro Tlaquepaque, home to some 700,000, that state and federal authorities assumed security duties this month, while more than 800 police officers were subjected to security checks. Most were later reinstated, but authorities say about 75 remained under investigation and off the streets.

The security takeover came after seven patrons were gunned down in a seafood restaurant in San Pedro Tlaquepaque in an apparent gangland hit, part of an uptick in killings and other crime in the district.

The escalating violence in Jalisco comes against a panorama of rising crime nationwide that is a contentious issue in the ongoing presidential election campaign.

Last year, Mexico recorded more than 25,000 homicides, an almost 25% jump from 2016 and the highest annual number since officials began tracking such data two decades ago.

In Mexico, cleaning up police corruption is a perennial political campaign promise, inevitably unfulfilled.

The government’s inability to rein in criminality has been a knock against the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto and his ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party. While Peña Nieto cannot seek reelection, polls show the ruling party standard-bearer running well behind in presidential elections scheduled for July 1.

Despite the widespread disquiet about violence and the protest marches, a semblance of normality somehow still prevails in Guadalajara and the vicinity. The daily TV images of slain victims dumped on streets or elsewhere have failed to dim the vibrant outdoor life here and elsewhere in Mexico.

In San Pedro Tlaquepaque, mariachi bands offer their services while tourists meander through the colonial-era streets, prowling handicraft outlets and taking breaks for margaritas, birria (roasted goat meat) and other Jalisco fare.

Red banners mark the reopening of the seafood joint known as Don Cangrejo (“Sir Crab”), where seven people were gunned down in February. But no patrons were present on a recent afternoon at Don Cangrejo, despite signs offering free beer and discount shrimp by the kilo.

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.