South Africa butterfly hunters: A rare breed

The leader of the net-toting group is Mark Williams, who has traveled widely, fending off baboons and dodging hippos and snakes, in search of his obsession.

- Share via

Mark Williams was out with his butterfly net in his favorite South African mountain range when a flutter of gray-blue wings sailed by. They were almost as small and nondescript as the other gray-blue butterflies drifting past.

Almost.

Heart pounding and net flailing, he dashed after the bobbing sliver of color, hope fluttering like a wind-blown flag. He hooked in the tiny creature, its wingspan just over 11/2 inches. It was a Lotana blue, believed to be extinct. Nobody had seen one alive in decades.

"I ran it down and caught it with a huge … swipe, because they can move," Williams said of that moment five years ago. "I knew straight away I'd rediscovered the Lotana blue."

His search for the Lotana blue had taken eight years. Yet a lepidopterist's life — the childhood bedroom stuffed with bird's nests, pebbles and butterflies, the years of research, the wild goose chases — can be distilled into such wild, joyful moments.

Dashing through the scrub, net aloft, is a passion that has not changed much over the decades — except that like certain butterfly species, the South African lepidopterist population has dwindled to a few dozen fiercely competitive fanatics, most of them middle-aged men.

And the 63-year-old Williams, a man who has traveled hundreds of thousands of miles with his trusty net, confronting angry baboons, dodging bull hippos and narrowly avoiding snake bites, is one of their gods.

I'm being called the Butterfly Whisperer."— Mark Williams

"I'm being called the Butterfly Whisperer," Williams said with a smile, carefully moving the remains of rare and common species from one pinboard to another. "I'd love to go out with that title. Mark Williams, the Butterfly Whisperer," he said, rolling the words as if savoring wine.

When Williams first announced his 2009 find, fellow collectors found it hard to believe until he published photographs online. Since then, Williams, who earns a living as a veterinary pathologist, has netted two other species not seen in decades: the Juanita's hairtail last year, and the Waterberg copper in March.

The Waterberg copper was so intensely sought that the Lepidopterists' Society of Africa distributed "wanted" posters with pictures of the insect, and offered a reward of about $1,000.

Searching for the copper, Williams used Google Earth to pinpoint an isolated plateau in South Africa's Limpopo province at the same elevation as the butterfly's former habitat, but 25 miles east. He took a weekend off and forged along a bush track, trailed by his wife.

As soon as he saw the orange flutter of wings, he laughed, not so much at the joy of finding it, but at the irony that he, as the founder of the society, would be collecting the reward. He plans to invest it in future butterfly searches.

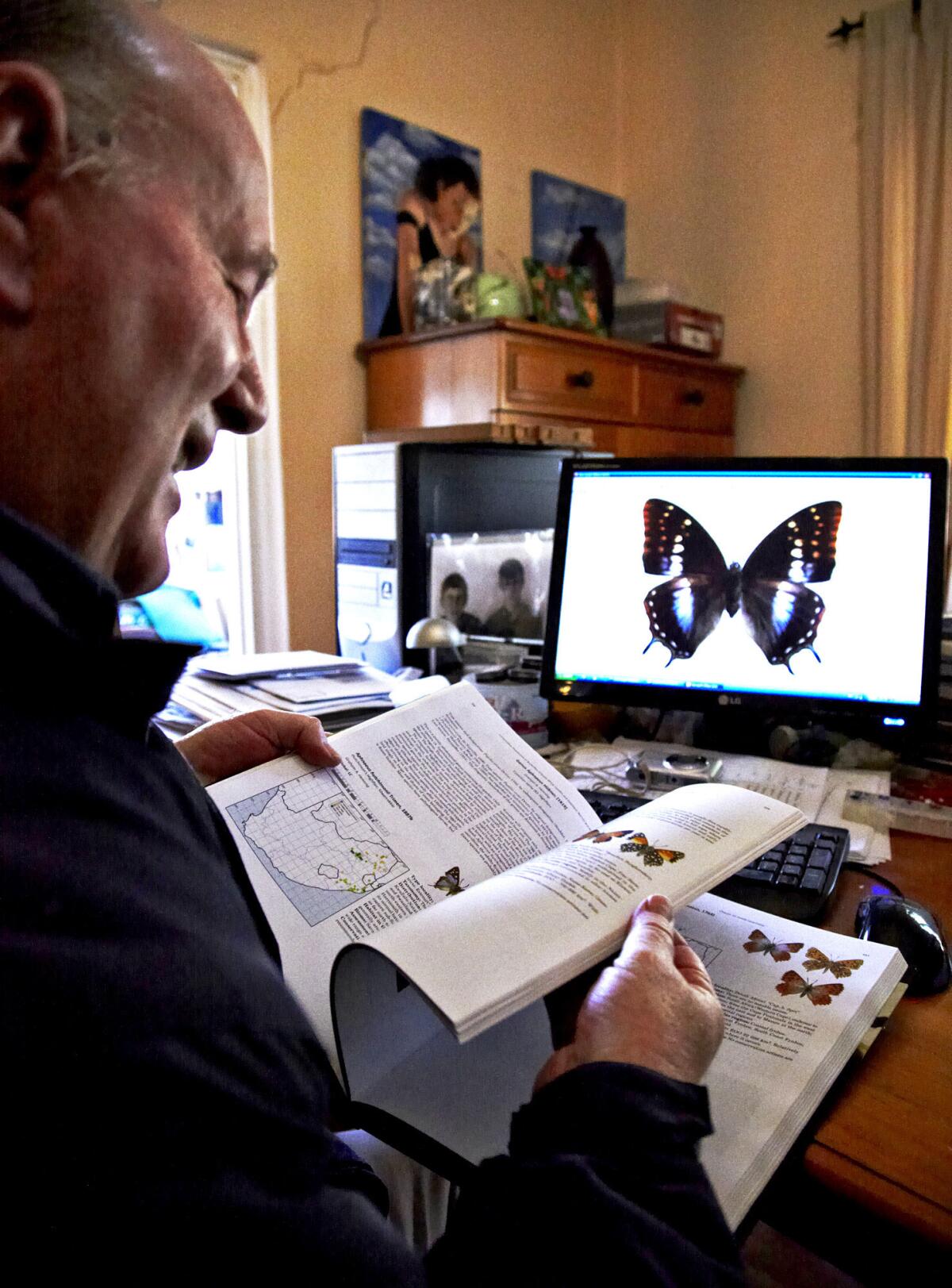

Although Williams is gregarious and talkative, he's happy staring at Google Earth on a computer screen, shifting locations, sifting for possible sites. He will spend hours looking up rainfall data for various locations (to help him get the timing of his expeditions right) and analyzing vegetation cover (to find the plants the caterpillars eat).

Mark Williams pages through a butterfly book he co-wrote searching for rare butterfly species. (Hannelie Coetzee / For The Times) More photos

Mostly, though, he has an edge because of the knowledge gained in more than half a century of tracking the insects in this land rich with butterfly species — about 650 of them.

Since Williams founded the Lepidopterists' Society in 1983, the hunt for endangered species has grown more urgent, with habitat loss and climate change threatening some species, particularly those that have retreated to the tops of mountains, looking for cooler air, and may soon run out of altitude if the highest peaks become too warm for them.

At the end of this year, Williams will launch a quest to rediscover the Bashee River buff — the holy grail for South African butterfly experts. If the buttery-winged creature still exists, it's most likely to be found on the densely forested banks of the Mbashe River, in the wilds of Eastern Cape province.

Williams likes to put himself in the shoes of collectors such as James Henry Bowker, a British colonel who in the 1860s was the first and last person to see the Bashee River buff, capturing three females, which he promptly pinned to a board and sent on to Cape Town.

Williams gets a faraway look in his eye at the thought of becoming the second person ever to lay eyes on the Bashee River buff, and perhaps the first to capture a male.

One of Bowker's specimens remains mounted in the South African Museum in Cape Town, the other two in British museums.

"It's 1 1/2 centuries it's been missing," Williams said. "We don't even know what the male looks like."

One problem with Williams' mission is that the buff might really be extinct.

"The cost of the trip is around 20,000 rand [$2,000] to go and look for a butterfly that I might not even find," he said.

Williams has read Bowker's letters about the buff, which is said to flutter around the tops of trees. He has gone back to Google Earth for any clues on habitat.

But when asked for details, Williams clams up. If he ever finds the creature, he says, then he will share such information. South African lepidopterists might be a tiny community, but competition can be cutthroat.

Williams stopped collecting most butterflies some years ago and instead began collecting eggs to hatch caterpillars. But when he finds a particularly rare one, he does capture and "set" it — a euphemism for pinning it to a board — to verify its identity.

Some of the butterflies captured by Mark Williams are on display in his office. He started collecting at 5 and says he was an avid lepidopterist by 7. (Hannelie Coetzee / For The Times) More photos

The act of killing a near-extinct species may surprise outsiders, but lepidopterists insist that taking a few specimens of rare species is essential, because mere sightings are not accepted as scientific evidence, given the complications of identifying the insects accurately.

"No knowledgeable lepidopterist would find it ironic. In fact, they would mostly likely be flabbergasted if voucher specimens were not collected," Williams said. "Five pairs of rhinoceroses, breeding remorselessly, would not reach a total population of a hundred in 10 years. Five pairs of African monarchs would reach about 36 million in six months. Laypersons don't understand this, unfortunately."

A friend and fellow member of the lepidopterists' society, Jeremy Dobson, said the scientific value of identifying and keeping track of rare and endangered butterflies outweighs the damage of capturing and setting small numbers of them.

Dobson, a soft-spoken, gentlemanly Englishman, is awed by Williams and other South African lepidopterists, and seems ready to pinch himself at the honor of being a member of such a society.

There are gentlemen's rules about sharing information in butterfly science, broken by one South African collector who, Williams said, was so possessive about lepidopterology that he regarded the insects almost as his own property.

Williams said he shunned the community, they shunned him, and "he died a lonely man."

At some point in his childhood, Williams' bedroom metamorphosed from a clutter of messy kid's curios into the beginnings of a serious butterfly collection. He started collecting at 5 and says he was an avid lepidopterist by 7.

He doesn't really know why he was attracted by butterflies.

"I'm a very curious guy," is all he will say.

As a schoolboy in the mid-1960s, Williams, accompanied by two friends, stumbled into a bush camp to find an old Chevy beside a tent and the well-known South African lepidopterist David Swanepoel, who had gorgeous azure butterflies pinned on a board.

Williams managed to annoy the old man, who had been collecting since the early 1900s, and who offered to show the boys where to find the creature. Though tantalized, Williams said he'd find it himself and watched in disgust as his two camping companions trotted after Swanepoel, "like obedient puppies."

"He called me a hard head and a little bliksem — a little rascal, or literally a lightning strike — and said I'd never find them. It took me three days. I worked my butt off.

He's had a couple of close encounters with leopards and deadly black mambas.

"And I came back and held it up and I said, 'I found it.' He leaned over conspiratorially. He said: 'Those other two will give up butterflies. But you will do this for the rest of your life.'"

In years of bushwhacking, he's grown used to sprinting across rocky ledges, looking both down (to avoid a broken ankle) and up (to avoid losing a butterfly). He's had a couple of close encounters with leopards ("You just run at them with a butterfly net") and deadly black mambas ("You just back off. You're in his territory").

Once, he scrambled up a tree in his red underpants when two bull hippos starting fighting just outside his tent. But his scariest moment came one morning at dawn when, as a long-haired young man in his 20s, he disturbed a baboon colony and was charged by four huge males.

"I stuck my net up over my head and stood on tiptoes. I bared my teeth. I gave a thunderous, inhuman screech which stopped them all in their tracks 15 meters away."

Then there was the angry farmer armed with a shotgun, who grabbed him for trespassing and took him to the police (but later gave him coffee and cookies in his kitchen as Williams showed him his specimens).

Williams conceded that the Bashee River buff search could prove fruitless. But if he finds it?

Well, that would leave him with one last great quest, for a species seen and collected just twice in the 1870s. The wily old butterfly hunter David Swanepoel went looking for it. But even he couldn't find the Morant's blue.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.