In China, press censorship protests continue

- Share via

GUANGZHOU, China — Like wedding guests separated across the aisle, the protesters assembled on either side of a gated driveway at the headquarters of the embattled Southern Weekly newspaper. To the right, several dozen supporters of the newspaper staff waved banners calling for an end to censorship of the Chinese press.

“Freedom!” they chanted.

“Democracy!”

“Constitutional rights!”

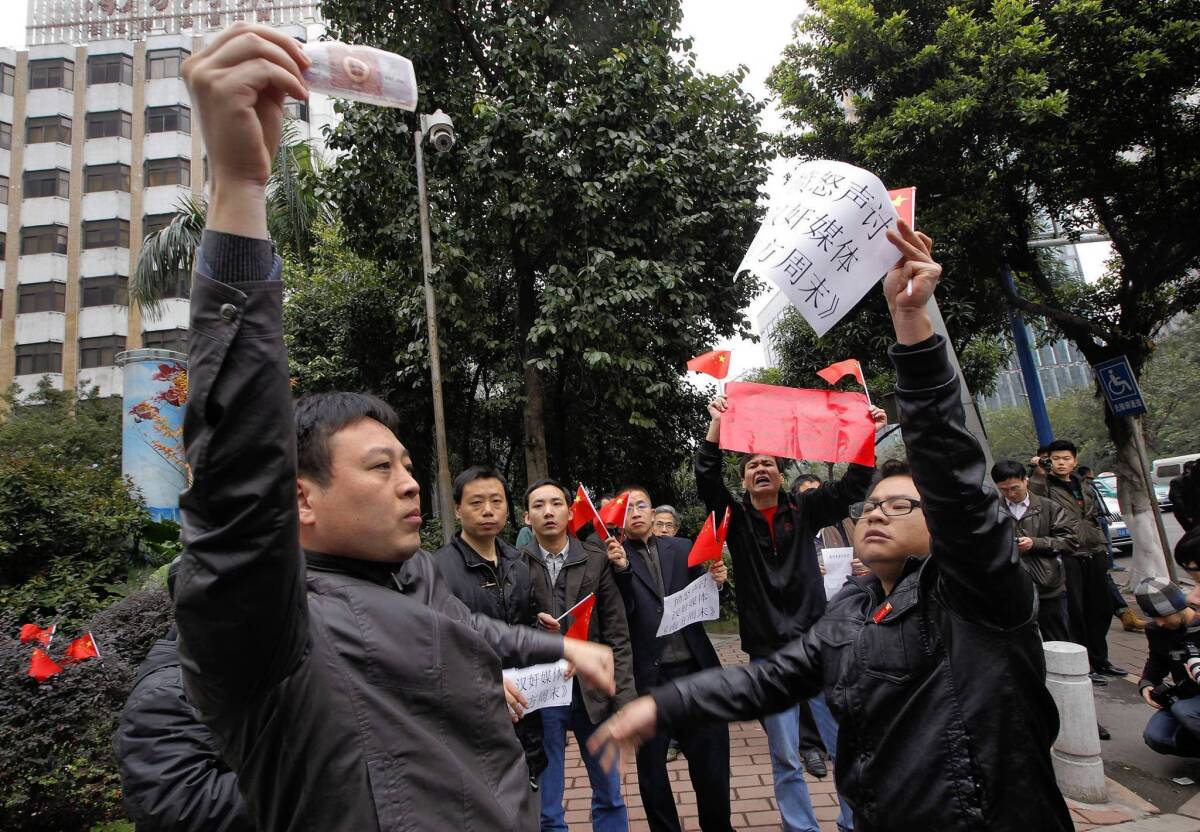

To the left, beneath fluttering red Chinese flags and hoisted portraits of Mao Tse-tung, a battalion of mostly older men shouted into a microphone, trying to drown out their ideological rivals.

“Long live Chairman Mao!” they chanted.

“We love China!”

“Patriotism!”

Across the divide, the dueling protesters have been engaging in a spirited debate over the Communist Party’s grip on the media. The spat erupted over the weekend in the southern city of Guangzhou when journalists threatened to strike over a front-page New Year’s editorial that was rewritten by propaganda officials. Although a strike was averted by a last-minute deal Wednesday, the raucous public protests continued outside the newspaper headquarters.

The protests were inspired by rising expectations after the 18th Communist Party congress in November, when the new leadership was installed. Xi Jinping, the new party secretary who will become president in March, has hinted at plans to uphold constitutionally guaranteed rights and fight corruption within the party. What role the media will play in that fight is at the heart of the debate.

One lesson of the Guangzhou protests is that the overarching conflict about the role of the press in a communist society is not likely to be resolved any time soon.

“You can’t fight corruption without freedom of the press,” said a 46-year-old activist, Xiao Qingshan, who demonstrated from a wheelchair (necessitated by a work injury) that was festooned with pro-democracy slogans. “We’re tired of being lied to. We want the same kind of freedoms as in the West.”

Protesters poked fingers in each other’s chests. They pushed. They shoved. Police who had planted themselves in the middle of the driveway broke up a few incipient fights but otherwise did not intervene.

A 73-year-old retired engineer wearing a Mao pin on his leather jacket hectored a university student who had dared to walk across the divide to debate.

“You young people don’t understand what’s going on. Who does this newspaper belong to? It belongs to the Communist Party,” lectured the older man, who would not give his name. “These journalists are civil servants who are supposed to obey orders, not behave like traitors following the United States.”

Indeed, despite a shift toward commercialization, newspaper ownership in China remains deeply lodged with the state. In order to operate, all of China’s more than 2,000 newspapers require a Communist Party or government organ to sponsor a publishing license. Inside each newsroom is a Communist Party secretary who makes sure the stories are politically correct.

The restrictive environment makes the journalism at the muckraking Southern Weekly and its sister paper, the Southern Metropolis Daily, all the more remarkable.

The publications belong to the Nanfang Media Group, which is owned by the government of Guangdong, China’s richest and most liberal province.

For several years, the Southern Weekly and the Southern Metropolis Daily were able to deliver stories that challenged authority and exposed unchecked power.

That was possible because the newspapers’ stewards had long belonged to liberal factions of the party, shielding it from interference, said Cheng Yizhong, who helped launch the Southern Metropolis Daily in 1997.

In May, the government installed a new party secretary at Nanfang, the first not to have originated from within the company. The appointment, along with the arrival of Guangdong’s new propaganda chief, Tuo Zhen, coincided with a decline in sensitive reporting, analysts say.

Journalists say 1,034 stories at the paper were censored in 2012. The propaganda department deleted an entire eight-page feature, involving work by seven journalists, profiling victims of the deadly July floods in Beijing.

“The anger at the Southern Weekly has been accumulating because of the barbaric way propaganda officials have been dealing with them for a long time,” said Cheng, who now works for a magazine in Hong Kong. “It reached a tipping point, and they lashed out.”

However, he added, “Realistically, I’m not very optimistic. The overall situation in China is that there’s still very strong opposition to reform and they’re trying everything they can to stop progress.”

Under the deal reached Wednesday, which reportedly was negotiated at high levels of the Communist Party, journalists will not be punished for their rebellion and censorship is to return to the milder levels to which they had been accustomed.

“They’re fighting for the status quo, which is hard to comprehend from a Western context,” said Jeremy Goldkorn, the Beijing-based editor of Danwei.com, which follows the media in China.

On the sidewalk outside the Southern Weekly, there was an atmosphere of a debating club.

“So what kind of freedom are you looking for?” a middle-aged man demanded of a young woman wearing a blue miniskirt and fake fur stole.

“Freedom to eat clean food. To have safe milk, safe pork, vegetables,” shot back the woman, Liang Xiaoran, referring to tainted-food scandals, some of which were exposed by the Southern Weekly.

Many people appeared to be genuinely conflicted.

“China is such a vast country with so many people and provinces. We are not like Taiwan or Hong Kong. If we don’t control things with a centralized system, it could fall apart,” ventured Chen Bin, a party member in his 30s who shyly approached some journalists on the sidelines of the protest. “But still we need our basic freedoms. Everyone has the right to speak out.” He applauded the Southern Weekly’s coverage of the underprivileged, citing exposes about forced labor in brick factories.

Most of the banner-wielding demonstrators were students and activists, with many passersby saying that they were there to lend support but were afraid to openly demonstrate.

A 45-year-old financial executive in a cashmere coat said she had not participated in a protest since 1989, when pro-democracy demonstrations at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square spread around the country.

“I had to be here to give my support. I love Southern Weekly,” said the woman, who gave only her English name, Tina. “My whole family reads it. My father reads every single issue and marks it up with a highlighter.”

Demick reported from Guangzhou and Pierson from Beijing. Nicole Liu of The Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.