The world’s smallest porpoise has caused a big battle in Baja California

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society is fighting the eradication of the world’s most endangered sea mammal, the vaquita. (Video by Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

- Share via

Reporting from San Felipe, Mexico — The small porpoise that swims off the coast of Baja California may be the loneliest creature in the sea.

Two decades ago, 600 vaquita marina splashed in these turquoise waves.

Today, fewer than 30 remain, the only ones left on Earth.

The vaquita — whose chubby frame, wide grin and black-ringed eyes have earned it the nickname “panda of the sea” — is veering dangerously close to extinction because of the appetites of a growing middle class 8,000 miles away.

Hundreds of vaquita have died in recent years after becoming entangled in nets set for the totoaba, a large white fish whose swim bladder can fetch thousands of dollars on the black market in China, where it is believed to have medicinal properties.

The prospect that the vaquita could disappear in a matter of months has inspired a controversial conservation campaign, with the Mexican government banning all fishing nets from a large swath of the Sea of Cortez, the narrow gulf separating Baja California from mainland Mexico.

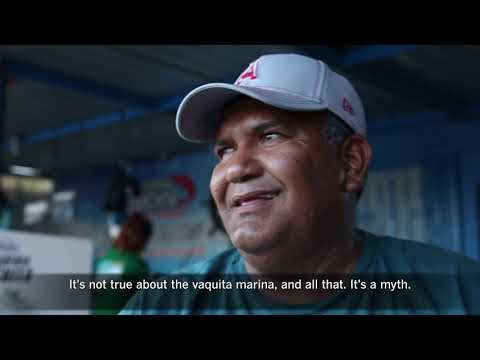

The government has paid tens of millions of dollars to help local fishermen who have found their profession suddenly outlawed. But the money has failed to quell rising anger in the port town of San Felipe and other beach communities strung along Baja California’s east coast. They see eco-activists who have descended on the area as foreign interlopers who care more about a handful of sea creatures than they do about the livelihoods of local Mexicans.

“Why are they coming from other countries and telling us what to do?” asked David Flores, who runs a small fish market along a dirt road here.

The vaquita is the world’s smallest porpoise, with the smallest geographical range of any marine mammal: Its entire habitat is a third of the size of Los Angeles County.

Yet it has become an international cause celebre.

Hollywood celebrities have tweeted about it, international conservation groups have launched campaigns and the U.S. Navy has offered to lend its trained dolphins this fall to help capture the remaining porpoises so they can be transferred to a special holding facility.

Because vaquitas take up to six years to reach sexual maturity, and then give birth only every other year, there has even been talk of trying to clone them.

But despite all the efforts, several dead porpoises have washed ashore in recent months.

The problem, authorities say, is that the illegal totoaba trade is more lucrative than cocaine trafficking. Mexican fisherman have been exporting totoaba bladders to China for decades, but in recent years, thanks to China’s booming economy, demand has soared.

In 2013, an American man was caught smuggling 27 totoaba swim bladders across the Mexican border. At his house in Calexico, authorities found 214 more — worth an estimated $3.6 million.

In late 2015, a ship carrying about a dozen hardcore ocean activists sailed into San Felipe’s sleepy harbor.

The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society had come to try to enforce the net ban that had been instituted by the Mexican government, but which was not being well enforced. Every day since, a team of vigilante volunteers from around the world has hauled up and destroyed nets illegally set by Mexican fishermen.

The activists are sometimes asked why they don’t devote their resources to bigger ecological issues. They say they view the vaquita as a small but powerful symbol.

“If we’re not able to save a small porpoise that is not needed by anyone, how are we going to be able to save all the other unknown endangered animals?” asked Raffaella Tolicetti, 30, the manager of a second Sea Shepherd vessel, the Sam Simon, which last year joined the first ship in patrolling the area the Mexican government declared a vaquita refuge.

Since the 1970s, the Sea Shepherd organization has carried out dozens of campaigns to help save marine life from human destruction around the world. It is most famous for its aggressive anti-whaling crusades off Antarctica, where its tactics, including ramming whaling ships, were documented by a reality television show called “Whale Wars.”

Dubbed “eco-terrorists” by the Japanese government and considered too radical by Greenpeace, the Sea Shepherd activists embrace an attitude and aesthetic that could be called “pirate-punk.” The group’s official uniform is a black shirt T-shirt emblazoned with a Jolly Roger pirate skull — crossed with a shepherd’s crook and a trident.

Tolicetti, who has spent most of the last eight years living on Sea Shepherd boats around the world, was joined on the Mexico campaign by her husband and a diverse volunteer crew that included an Australian speech pathologist, a New Jersey engineering student, and a young French architect who said she came to Mexico because she was sick of office life and staring at her computer screen.

On one recent evening, as the sun dipped below the craggy mountain range that lines the sea’s western shore, Tolicetti gazed at the waters while another activist tracked several just-launched boats on an infrared screen.

With a storm moving in, the crew had anchored for the night. But usually when the activists believe they have identified a totoaba fishing boat, they speed toward it and launch camera-equipped drones to try to record illegal acts. They post videos online and share evidence with the Mexican Navy. Angry fishermen sometimes try to knock drones from the sky with bottles or other objects.

While some countries have sought to stop Sea Shepherd activism, this time the group has the blessings of the Mexican government — a sign, in part, of the government’s inability to stop the poachers on its own. Naval ships frequently sidle up to the Sea Shepherd vessels and offer to help recover the nets Tolicetti calls “indiscriminate killing machines.”

So far, the group has recovered and recycled hundreds of illegal nets, which also trap dolphins, whales and other wildlife.

“When you pull a net out of the ocean, it feels like the ocean is breathing again,” Tolicetti said.

But in the coastal communities of Baja, many residents don’t understand why their government has allowed in a group of activists they feel are out to ruin their way of life.

A few months ago, hundreds of fishermen in San Felipe called for the activists’ ouster in dramatic fashion: they painted “Sea Shepherd” on the side of an old boat and burned it, drawing cheers.

A leader of the protest, Sunshine Antonio Rodriguez Peña, was recently ordered to stay away from the captain of the Sam Simon after the captain filed a restraining order against him.

Juan Pablo Mesa, 21, understands his community’s anger. His grandfather was a fisherman, his father was a fisherman, and Mesa started fishing shrimp when he was 12. Before the net ban, he and his crew would catch 400 to 700 pounds of shrimp per voyage and he’d earn up to $3,000 a month.

In 2015, President Enrique Peña Nieto traveled to San Felipe and announced a sweeping plan: the government was widely expanding the vaquita reserve first created in 1993 and providing aid to help fishermen develop vaquita-friendly traps, nets and trawls.

Since 2015, Mesa has been paid a stipend of $430 a month by the government to stay out of the water. He complained that the government’s plan to develop new fishing techniques is taking too long.

On a recent afternoon, Mesa was working a construction project at a small campground on the beach in San Felipe, whose cheap hotels and pharmacies offering discount Viagra and other drugs without a prescription helps draw a small but steady stream of American tourists.

Mesa and his friends used to spend days at sea on fishing excursions, exercising together on deck to pass time and breathing in the ocean air as they slept. Now they are marooned on land, he said, and are getting fat. Because of the net ban, fish costs more at the market, so more locals are eating hamburgers instead.

“It’s a completely different type of life,” he said. “I miss it.”

In a reflection of Mexicans’ mistrust of their leaders, he and others suggest the government may be using the vaquita as an excuse to clear the waters so oil exploration can begin. After all, Mesa has never seen a vaquita in real life.

“We think it’s a lie, a pretext to get oil,” he said.

Or maybe the vaquita exists, he said, but is dying for other reasons. He blames Americans, who take so much water from the Colorado River that it no longer flows into the gulf, increasing the salinity of the Sea of Cortez. He said he understands why many totoaba fishermen haven’t stopped. “They’re just trying to survive,” he said.

And the environmentalists are determined to thwart them. On a recent morning, the Sam Simon was cutting careful patterns in the water, dragging behind it two large hooks designed to snag nets, when suddenly, a line went taut.

Caroline Scholl-Poensgen, 20, a lanky environmental studies student from Germany, hopped into a smaller boat with Giacomo Giorgi, 34, an Italian punk rocker, and sped out to where the hook had snagged a net.

“Oof, it smells like totoaba,” Giorgi said, covering his nose with his shirt. His camouflage shorts revealed legs covered with tattoos, including the word “animal” inked on his right calf and the word “liberation” inked on his left.

Sure enough, as they started pulling up the net, they found the decomposing body of a large white fish the size of a small child. Its stomach had been slashed open, the swim bladder extracted. Its organs were floating outside its body.

An activist assigned to the media team documented the dead fish with his camera before Scholl-Poensgen freed it, its flesh falling off in chunks.

As she threw it into the sea, black birds circled to eat it.

They wouldn’t spot any vaquitas, but she and Giorgi would find 11 more totoaba bodies that day.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

Twitter: @katelinthicum

ALSO

200 cows take over downtown San Diego. ‘What could possibly go wrong?’

Someone left 15 hedgehogs to die in beach trash can, San Diego authorities say

Where is the lost fishing boat Tammy? Two wreck hunters think they know

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.