When it comes to raising a child disabled by Zika, Brazilian women often do it alone

- Share via

The day Josemary Gomes brought her newborn son Gilberto home to a tiny pink house on a sun-baked cobblestone street, she laid him on her bed and wept.

But there was no one to comfort the single mother. “I raised my head,” she said, “and carried on alone.”

Gomes is among a growing number of women in Brazil who are raising children damaged by the Zika virus on their own.

As many as a third of mothers are unmarried in this nation of 200 million, the hardest hit in an epidemic that has swept around the world. Studies suggest that the rate is highest in impoverished rural villages and crowded slums — the places most affected by the mosquito-borne virus that has been linked to at least 1,638 cases of birth defects across the country.

Even mothers who have a partner have found themselves suddenly abandoned as their relationships crumble under the emotional strain, economic burden and social stigma that come with raising a child who may require almost constant attention.

“We think it just becomes too hard for the men, at least from their point of view,” said Simone Jordao, who heads a treatment center for children with disabilities in northeastern Brazil, the epicenter of the Zika outbreak. “They may try at first, but then they drift away — or leave the family forever.”

Babies with microcephaly — an abnormally small skull, often accompanied by brain damage — tend to be more easily agitated than other infants and cry incessantly. Many develop severe cognitive and physical disabilities and need expensive therapies and monitoring by specialists.

Caring for these children is so difficult that staffers at the region’s hospitals worry that, without the help of a partner, some mothers might abandon them.

That has happened in a few cases in the northeastern state of Pernambuco, where the surge in microcephaly cases began last year, and in the coastal city of Rio de Janeiro, to the south. Orphanages commonly take in children with disabilities, and in some hard-hit cities, they are bracing for an increase in admissions.

The fear for children damaged by Zika is compounded by the poverty and youth of many of the parents, some of them teenagers.

Many of the families who come to Jordao’s center, in the Paraiba state capital of Joao Pessoa, are “in situations that are very precarious, either financially or socially,” she said. “We have many situations where the husband is in prison, for example…. These families need support.”

Gomes, 34, already was raising four boys on her own when she met Gilberto’s father.

She thought he would take care of them. But when she got pregnant, she said, he told her he was already married.

At least he sometimes sent money to help with expenses.

When the labor pains started, she caught a bus alone to the maternity hospital, about an hour away in the city of Campina Grande.

She was still recovering from the birth when a doctor came with questions. Had she been infected with Zika?

Yes, she said, when she was seven months pregnant.

The doctor told her that Gilberto’s head was unusually small for his body size: He had microcephaly.

She thought the doctor must be mistaken. Two ultrasound exams hadn’t revealed any problems during the pregnancy. When Gomes called to tell the father, she said, he refused to accept that the baby had a malformation.

“He said, ‘No. No way,’ ” she recalled. “I asked him, ‘Why? Do you have any prejudice?’ He said no.”

She didn’t believe him. People with disabilities are heavily stigmatized in Brazil, especially in the conservative and impoverished northeast, where some view the babies with microcephaly as beset by demons.

It was weeks before Gilberto’s father visited him, Gomes said. The money for expenses soon stopped arriving.

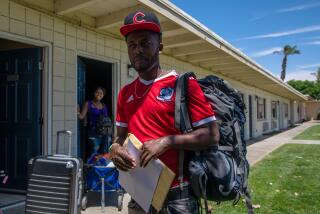

He occasionally stops by the house, usually to see Gomes’ 17-year-old son, Joao Victor, with whom he remains close. But when he saw a Times reporter and photographer there one afternoon, he rode away on his motorcycle. He could not be reached for comment.

Gomes has started calling herself a “warrior mom.”

Her days revolve around the 8-month-old boy, who is showing signs of developmental delays and has started having convulsions.

When Gilberto’s crying becomes too much to bear, his mother lifts him into a blue plastic tub set on the kitchen table.

“Are you hot, my love?” she asks, scooping water over his head. It’s the only way to soothe him.

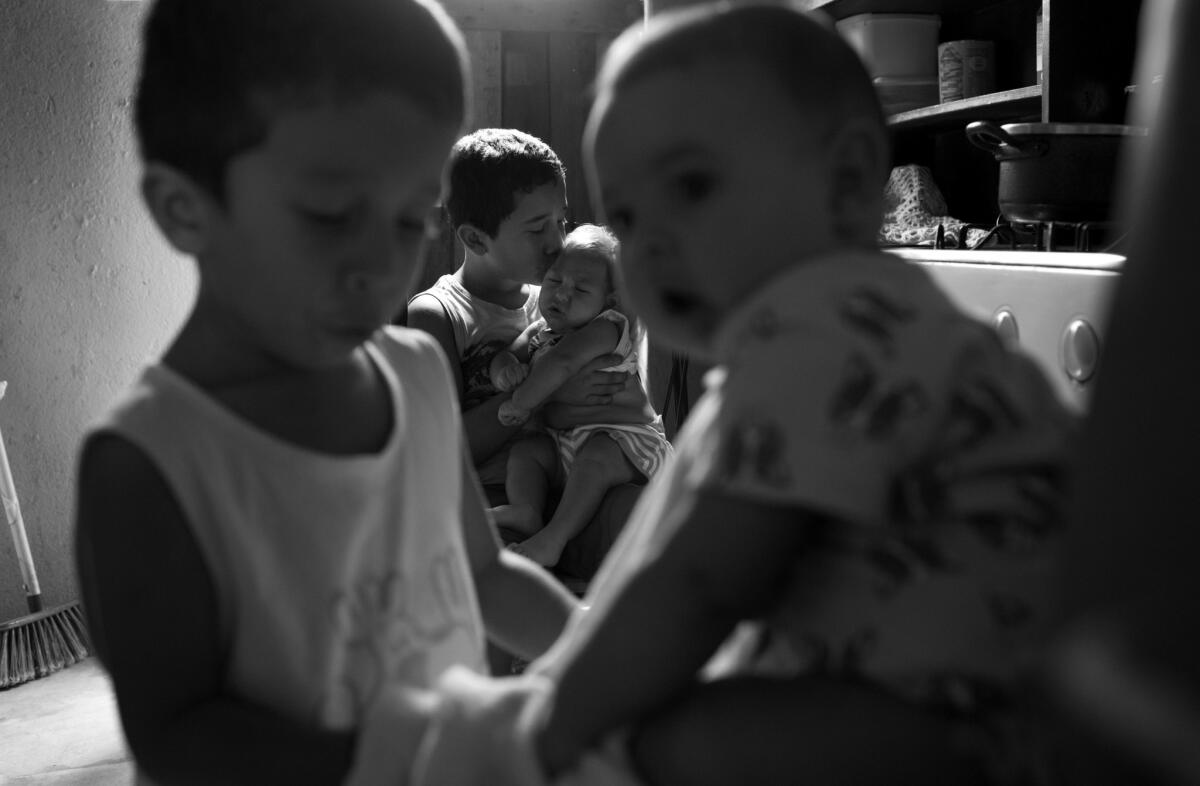

When it’s time to start cooking rice and beans for lunch, Gomes hands Gilberto to his 9-year-old half-brother, Marcos. He has to be held or he starts crying again.

Medical appointments seem to rule her life.

Gomes sets her phone to wake her up at 3:45 a.m. most days. She dresses and feeds Gilberto in the dark, lays food out on the kitchen table for his brothers and hurries out the door to catch the free municipal car that brings patients to Pedro I Municipal Hospital in Campina Grande.

“I’m always late,” she lamented.

At the hospital, parents are encouraged to take part in the children’s physical therapy sessions. Gomes and Gilberto are surrounded by mothers and babies with microcephaly. Fathers hardly ever show up.

Jacqueline Loureiro, a psychologist there who runs support groups for the mothers, estimated that of the more than 40 women she counsels, 3 out of 4 don’t receive the emotional and financial support they need from a partner — even if they are living with the father.

“This society is still very macho, so the father might be there but not be involved at all,” she said. Nor is he likely to help with cooking and cleaning at home, though he might contribute financially.

Before Gilberto was born, Gomes cooked and cleaned at a restaurant. Now her only income is from a government program that pays a monthly stipend to poor families. She gets about $130 a month.

Her home is so small she must share a bed with three of her children. There is no air conditioning or running water. Mosquitoes that breed in the backyard water tank torment the family at night.

“Sometimes I think about getting out of here,” she said.

But the rent is cheap, less than $40 a month.

The hospital has encouraged her to apply for an additional benefit available to parents of children with disabilities. But the application process is cumbersome, and she must first correct an error on one of the boys’ birth certificates.

When she runs out of money, she picks up diapers and baby lotion from a storage room at the hospital, which has received a flood of donations since the Zika crisis began.

She used to be ashamed to ask for help. Now, she says, she’ll ask anyone.

“I am Gilberto’s father now,” she said. “I am mother and father at the same time.”

Special correspondent Vincent Bevins in Sao Paulo contributed to this report.

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

Twitter: @alexzavis

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.