- Share via

Melissa and Daryl McKinsey first heard about “Mexican Oxy” last year when their 19-year-old son Parker called in tears.

“I need to go to rehab,” he said.

Several months earlier, a friend had given Parker a baby-blue pill that was stamped on one side with the letter M.

It resembled a well-known brand of oxycodone, the prescription painkiller that sparked the American opioid epidemic.

But the pill was actually a far more powerful and more addictive opioid: fentanyl.

Within weeks, Parker was crushing and freebasing up to eight pills a day.

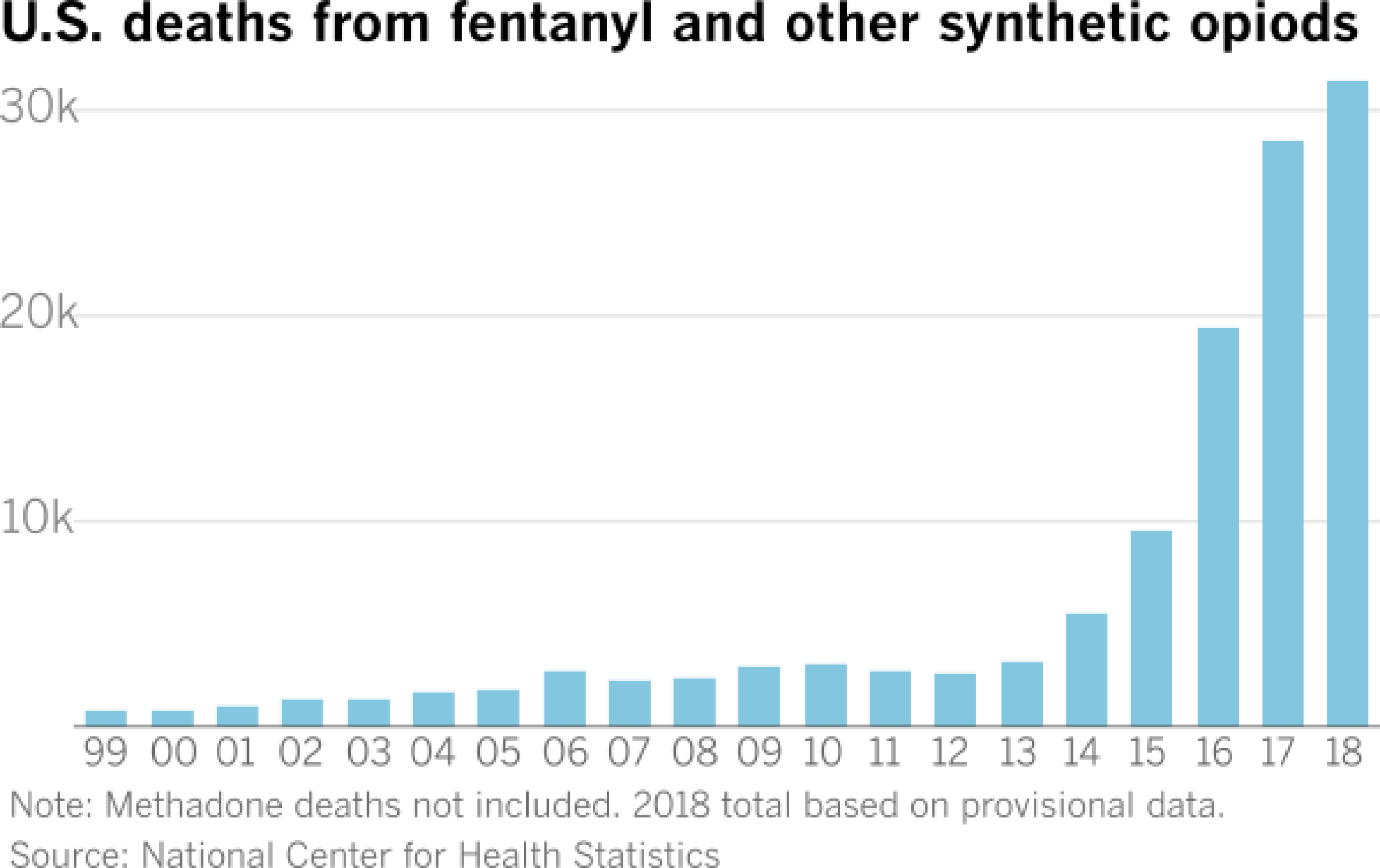

Developed decades ago as a painkiller of last resort, fentanyl has surpassed heroin and prescription pills to become the leading driver of the opioid crisis and is now the top cause of U.S. overdose deaths.

Last year, more than 31,000 people in the United States died after taking fentanyl or one of its close chemical relatives, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No other drug in modern history has killed more people in a year.

Fentanyl started appearing on U.S. streets in significant quantities in 2013, most of it produced in China and shipped in the mail.

Today, officials say the majority is smuggled from Mexico, where it is remaking the drug trade as traffickers embrace it over heroin, which is more difficult and expensive to produce.

While heroin is made from poppy plants that grow only in specific climates and take months to cultivate, fentanyl and other so-called synthetics are cooked from chemicals in makeshift laboratories in a matter of hours.

U.S. border agents have been intercepting increasing amounts of fentanyl. In January, they reported their largest seizure ever: 254 pounds of powder and pills hidden in a truck carrying cucumbers into Nogales, Ariz.

Parker McKinsey grew up 200 miles north of there, in the idyllic Phoenix suburb of Buckeye. American flags and wind chimes hang from porches, and traffic is so light that residents sometimes drive golf carts on the streets.

His parents raised him and his younger brother Bryan to believe in two things: God and baseball. Best friends, the boys were blond and blue-eyed and were both standout high school players, competing each summer in the nation’s top club leagues.

Parker, who had a rebellious spirit and had struggled with school, was devastated when he failed to attract interest from college teams. After graduating in the spring of 2017, he fell into a depression, and slipped from smoking marijuana into stronger drugs.

It was Bryan who urged his parents to heed his older brother’s plea for help.

“He could die,” Bryan warned.

The McKinseys dug into their savings to enroll Parker in a $20,000-a-month rehab facility.

The morning they dropped him off, his mother, an elementary school principal, thought to herself: “This is the worst day of my life.”

That day, however, was still to come. The culprit, again, would be a blue pill stamped with the letter M.

::

Fentanyl has also had a profound effect in Mexico, where it has upended the drug economy, creating new opportunities for some traffickers and producers, while putting others out of business.

Ruperto Pacheco Vega wasn’t yet born in the early 1970s when strangers showed up in the hills of southern Mexico bearing gifts of poppy seeds. They showed locals how to raise the plants and how to extract the gum that oozed from their bulbs.

Three times a year, during the harvest, the strangers returned to buy the gum, which they eventually turned into heroin.

Pacheco was 8 years old when he began helping his father cultivate poppies on their hillside farm in the state of Guerrero. It was one of the few ways to make a living there.

He said poppy prices held steady for many years — until 2011, when they began to surge.

He didn’t know it, but the U.S. opioid epidemic was entering a new phase.

For years, American doctors had been overprescribing oxycodone and similar painkillers. But increased regulation had made those pills harder to get legally, so addicts turned to heroin.

In Guerrero, the going price for opium reached a peak of $600 a pound. Opium production in 2017 outstripped legal agricultural output in the state by about $132 million, according to the international policy think tank Noria Research.

By that year, poppy fields in Mexico covered 109,000 acres, more than triple the total six years earlier.

Pacheco, now himself a father, remembers that golden period happily. After a lifetime of subsisting on tortillas and beans, he could finally afford to buy his family beef.

He and other poppy farmers faced eradication campaigns by the Mexican government and had to navigate periodic turf battles between cartels, but the money kept flowing.

Then two years ago, prices plummeted. Today a pound of opium goes for less than $100.

Four of Pacheco’s five children have migrated to the U.S. in search of work. There is not enough money to pay his youngest son’s $40 high school tuition or to buy candles for the altar to the Virgin of Guadalupe they keep in the corner of their house.

In May, 43-year-old Pacheco harvested opium gum on his family’s plot of land for the final time. He replaced his pale pink poppy plants with corn.

A local heroin laboratory now sits abandoned.

When Pacheco asks the opium buyers what happened, they all say the same thing: “The synthetics collapsed everything.”

::

On a ranch in northern Mexico, a 23-year-old dons a hazmat suit, fires up a camping stove and begins cooking a gurgling cauldron of chemicals.

The key ingredient, smuggled from Asia, is a molecule called 4-anilino-N-phenethyl-4-piperidine.

He takes care not to let the mixture touch his skin. He’s seen other fentanyl cooks get high from the drug while preparing it, and has heard of others who have overdosed and died.

The cook, who spoke on the condition on anonymity, was a cattle rancher before he learned how to make fentanyl on the Internet.

“You earn more,” he said. “It is less work and less investment and more profit.”

He and his business partners, two other cooks in their 20s, work outside the city of Culiacan with the permission of the Sinaloa drug cartel.

In two years in the business, he said, he has acquired six vehicles. He recently opened a car wash as a means to launder money.

The original fentanyl cook was a Belgian chemist and pharmaceutical developer named Paul Janssen, who was looking for a painkiller more powerful than morphine when he synthesized fentanyl for the first time in 1960.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved fentanyl eight years later to anesthetize patients during surgery. It was later developed into a skin patch for terminal cancer patients and others who had become tolerant to other strong opiates.

Years later, as opioid addiction rates soared in the U.S., chemists in China and elsewhere began making the drug illegally and selling it to Americans over the dark web.

U.S. drug dealers started sprinkling it into heroin and even cocaine to make their products more potent — in 2016, 11% of heroin samples analyzed by the Drug Enforcement Administration contained fentanyl or related substances, and that figure is believed to have significantly grown.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Overdoses skyrocketed. Fentanyl deaths exceeded heroin deaths for the first time in 2016. Last year, there were twice as many.

Fentanyl is 50 times stronger than heroin, and ingesting just a few grains — as little as a quarter of a milligram — can be deadly.

Public health experts denounced fentanyl as the third wave of the opioid crisis — after prescription pills and heroin — but Congress and the Obama administration were slow to act.

Meanwhile, Mexican drug traffickers came to understand the magnitude of the business opportunity and started importing fentanyl and the chemicals to make it themselves.

Officials say fentanyl can be up to 20 times more profitable than heroin.

It costs $32,000 to produce one kilogram of fentanyl, according to a task force of U.S. law enforcement agencies known as the Fentanyl Working Group. That 2.2 pounds can be used to manufacture one million pills with a street value of $20 million.

Fentanyl has another advantage for Mexican drug traffickers.

The narcotics trade in Mexico has become increasingly decentralized, in large part due to a decade-long strategy by the Mexican government to combat drug trafficking by capturing or killing cartel capos.

For smaller, leaner criminal operations, fentanyl is a perfect match. It’s much easier to buy precursor chemicals from smugglers than it is to control wide swaths of poppy-growing territory.

“It’s a very low barrier of entry,” said Steven Dudley, an expert on Latin American crime.

The days of the the Mexican cartel as “a monolithic vertically structured criminal group” are ending, he said.

“That model is a relic of the past,” Dudley said. “And the synthetic drug market may accelerate its demise.”

::

Inside an air-conditioned mall in an upscale neighborhood in Culiacan, a 43-year-old drug trafficker was finishing off a cup of ice cream.

The trafficker, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said he too is part of an independent cell that works with the authorization of the Sinaloa cartel.

Keeping his business small was a choice he made after seeing law enforcement target powerful leaders, such as former Sinaloa chief Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman.

“I’d rather be a small fish,” he said. “Because the authorities only go after the big ones.”

Dressed in flip-flops and a polo shirt, he said he got into the business 15 years ago, following in the footsteps of his father, a marijuana smuggler.

At first, the trafficker only moved pot too, but as U.S. states began legalizing marijuana, reducing demand from Mexico, he expanded to methampetamine and then heroin.

Over the last two years, demand from the U.S. dealers that he supplies has changed.

They used to ask for shipments that were 90% heroin and 10% fentanyl. Now it’s the other way around.

“It’s not that the customers are asking for it,” he said of fentanyl. “The dealers are. It’s more productive for them. They can make more money.”

Though fentanyl has been good for business, he said it weighs on his conscience. When drugs are cooked in independent laboratories, errors can occur, and word has trickled back from his network of U.S. dealers that certain batches were bad, and probably caused deaths.

“The truth is, I’m the least proud of sending that drug,” he said of fentanyl. “But if I don’t send it, I’ll be out of business.”

At least with marijuana, he said, “I knew it wasn’t going to kill anybody.”

He dreams of saving enough money to move his family to the countryside, of starting an organic egg farm and leaving the drug business behind.

Typically he traffics fentanyl powder, but he sometimes smuggles fentanyl pressed into pills.

Last spring, he sent a large shipment up to the Arizona border. They were blue, and stamped on one side with the letter M.

::

Bryan Dale McKinsey, a pitcher for the Verrado High School baseball team, took a pill he believed was oxycodone and never woke up. The medical examiner’s report found the pill contained fentanyl and ruled his death an accidental overdose.

Melissa and Daryl McKinsey, preoccupied with helping Parker get clean, didn’t think they had to worry about their younger son Bryan.

He was the even-tempered child. The tattoo his parents let him get on his right forearm on his 17th birthday — a cross with a baseball in the middle — attested to his passions.

He had been a varsity pitcher since his freshman year and had attracted the interest of dozens of colleges. In early 2018, he flew out to St. Louis University for an official visit, and he told his mother he planned to commit to go there.

While his brother was still in rehab, Bryan was playing the best baseball of his life. At a game on May 3, he threw a fastball with the bases loaded in the final inning, clinching his team a spot in the state semifinals.

Five days later, he went into his parents’ room, like he did every evening, and kissed his mom good night.

The next morning, Melissa rose at dawn and went to work. Daryl, a delivery truck driver, was still out on an overnight shift.

Daryl didn’t think much of it when one of Bryan’s friends called, saying Bryan hadn’t texted her to say good morning like he did every day. Daryl drove home and opened the door to Bryan’s room, expecting to find him still asleep.

The lights were off, the television was on and Bryan was sitting up in bed wearing a baseball hat. Daryl touched his cheek. It was cold.

In Bryan’s pocket, police found several blue pills stamped on one side with the letter M. A toxicology report listed fentanyl as the cause of death.

His parents don’t know where he got the pills or why he took one. He didn’t have chronic pain, and he was well aware of his brother’s struggle with the drug.

“He could die,” Bryan had warned them.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.