Amid Mexico’s quake chaos and rumors, a website helps people get facts straight

- Share via

Reporting from Mexico City — In the hours after a 7.1 earthquake thrashed Mexico City on Sept. 19, half-truths and rumors were spreading rapidly. So, too, were urgent questions: Which intersections had become death traps, subject to falling rubble? Where was help needed?

A day later, the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods were flooded with volunteers, sacks of hastily prepared sandwiches and bottles of water. But more esoteric needs, like walkie-talkies, tetanus shots and harnesses, were harder to come by, and areas farther afield had yet to receive help.

For Antonio Martinez Velazquez, the founder of the online magazine Horizontal, it was immediately obvious that a tool was needed to organize volunteers, debunk myths and highlight real needs and dangers.

While Martinez and his colleagues noted that the government had released a map, they decided to embark on a distinct project: They created a map with carefully verified information and kept it continuously updated. Their map would be socially engineered, providing usable, rigorous information that would direct help where it was needed most. They called their effort Verificado19S, as in verified and related to the 19th of September.

A handful of volunteers quickly expanded to 400 on-the-ground fact-checkers, dispatched to the streets to confirm or debunk reports. The group began filling in a map with ever-changing data about trapped earthquake victims, required supplies, available shelters and more. By Monday, nearly 8 million unique users had visited their site, and more than 500 volunteers had contributed to the effort in their office.

And though this work was prompted by distrust of officialdom, the group is now collaborating with the government to merge different mapping endeavors to greatest effect.

Horizontal’s effort and its rapid success speaks to a generational shift since the 1985 earthquake. In the intervening 32 years, the term World Wide Web was coined and a cohort of tech-savvy chilangos, as Mexico City residents are called, learned to use social media to crowd-source information, whether to find the best place for vegan tacos or, since Sept. 19, how to best disseminate earthquake relief.

The effort reflects the Internet’s three virtues, as described in an early manifesto by online pioneers: “No one owns it, everyone can use it and anyone can improve it,” Martinez said. “Those principles are at the core of our generation, they are part of our social transactions and social forms of organization. That’s key in this network of Verificado19S.”

That facility with the Internet, both as a tool and as a concept, includes familiarity with one of its dangers: the spread of false information. And even if such untruths aren’t seeded with malicious intent, their impact can still be damaging.

“We wanted to concentrate information and try to avoid fake news,” said Sergio Silva, a member of the fact-checking team.

While Verificado19S can’t stop false rumors from starting, the volunteers monitor social media and review reports submitted by phone or through the website. When information is confirmed, they update the site and tweet bulletins with time stamps. In the process, they encourage the public to fact-check stories before passing them along.

On Sunday, at the site of a collapsed office building in Roma, actress Johanna Murillo assisted fact-checking efforts. As hundreds of volunteers, rescue workers, doctors, cooks, masseuses and others circulated, she kept the office updated on what supplies were needed and which were not. Murillo said that areas like that one, where victims were still trapped beneath rubble, were especially prone to the spread of rumors.

“Information changes every two minutes,” she said, “and it’s very important to maintain a sense of calm because people have conspiracy theories.”

A few minutes later, a volunteer came to chat with Murillo, retelling a story of a group of victims that had been rescued from the building.

A great story, but not one to disseminate. “It’s something people are saying, but we don’t know if it’s true,” Murillo said.

Alejandro Hope, a political analyst, said the will to believe optimistic stories is a natural instinct.

“People are wearing their hearts on their sleeve and they’re sensitive to both good and bad news. They want to believe there are people still alive under the rubble,” Hope said.

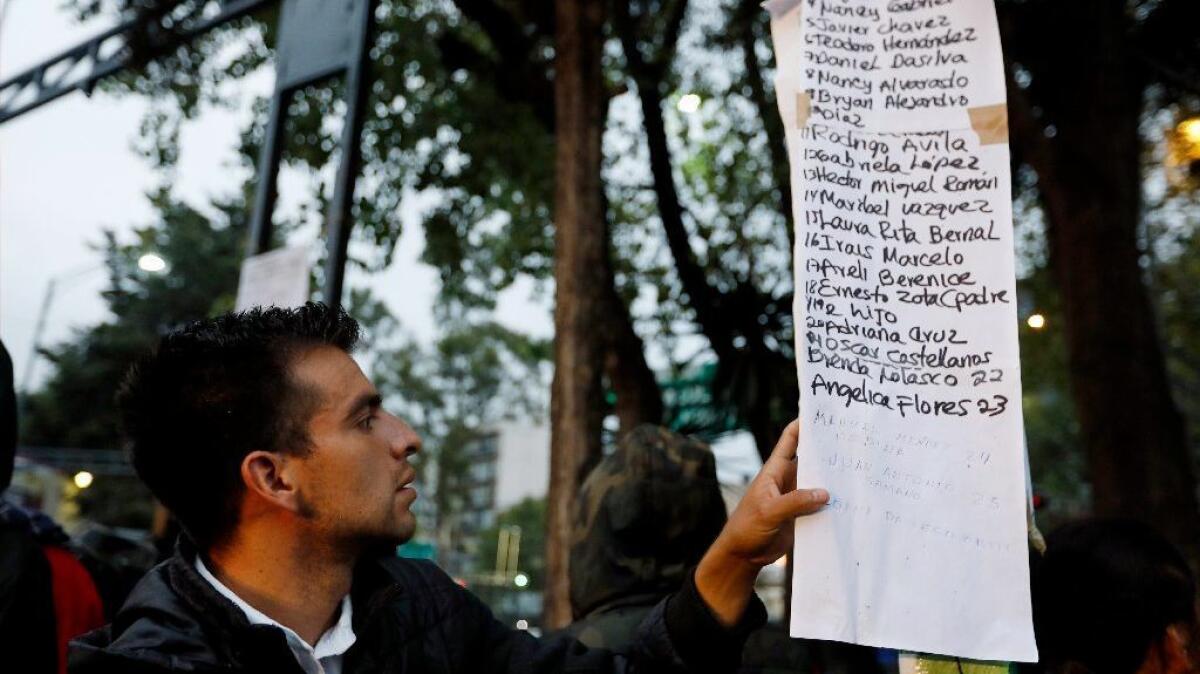

Across the city, rumors have percolated since the quake. On social media, a rumor quickly caught fire that an aftershock would devastate the city, even as scientists insist it’s impossible to predict earthquakes well in advance. In the Xochimilco area, a health worker held a hand-written sign up to passing cars, letting locals know that talk of a hepatitis outbreak was groundless. A nationwide audience was pinned to their television sets mid-week as rescuers searched for “Frida Sofia,” a girl supposedly trapped in a collapsed school. It turned out she never existed.

Analysts said these inventions, both big and small, can occur in a crisis anywhere, but are more prone to germinate in Mexico than in other theaters of catastrophe. Here, locals have a well-founded skepticism in official information and are more likely to value word from a neighbor, friend or shop owner.

“You can see we’re in a very deep crisis of trust between people and the government,” said Rodolfo Soriano Nunez, a public policy analyst. Nunez said that disturbingly, that distrust is justified. In Oaxaca, for example, rumors have spread that aid is not reaching the places it’s most needed and deliveries are sometimes stolen by government entities. Nunez didn’t doubt this was true. “I know the public officials there, and they are rats or cockroaches,” he said.

When official information lacks credibility, even places labeled as safe leave people feeling anxious.

On Saturday, Erika Hernandez, a janitorial worker in Roma, looked skeptically at the office building where she works.

“They say this building isn’t damaged, but it scares me to go in,” Hernandez said. “But you have to go to work.”

Hernandez said the story about Frida Sofia, which had captivated her attention as it had millions across the nation, only added to her overall sense of uncertainty.

“You don’t know what to believe or not,” she said.

To Martinez, the Frida Sofia episode was the prime example of the government’s failure at transparency. To allow only one TV network, Televisa, into the restricted area around the school, and then fail to make a correction when they continued to reference the nonexistent girl’s plight for hour after hour, would not have occurred if they were committed to the open passage of information.

“It’s a problem that it distracts people from what really is happening,” Martinez said.

On Tuesday, a week after the earthquake, much had changed. Information was getting out, some damaged sites were being reached for the first time, and fewer supplies were duplicated in densely populated areas.

Another key factor had shifted: Verificado19S was now working in collaboration with the government’s digital effort. The groups joined forces to create a master map, including everything from death tolls to photos of damaged buildings, and had also received assistance from Google.

Martinez said the new alliance wouldn’t fundamentally change his perspective on institutional corruption and disorder, but he knew a bright spot when he saw it.

“People have to continue to be skeptical of the government, because we know from our investigative journalism that they’re not trustworthy, but that should not cancel out the possibility of collaboration.”

Up to now, he said, the people had clearly trusted his group more than officials. Still, he added, “for the next step, it’s evident that collaboration is necessary.”

It would be a long road ahead.

ALSO

Saudi Arabia says ban on women driving to end next year

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.