For Mexico, Trump’s retreat on NAFTA is ‘like being drenched by a pail of cold water’

- Share via

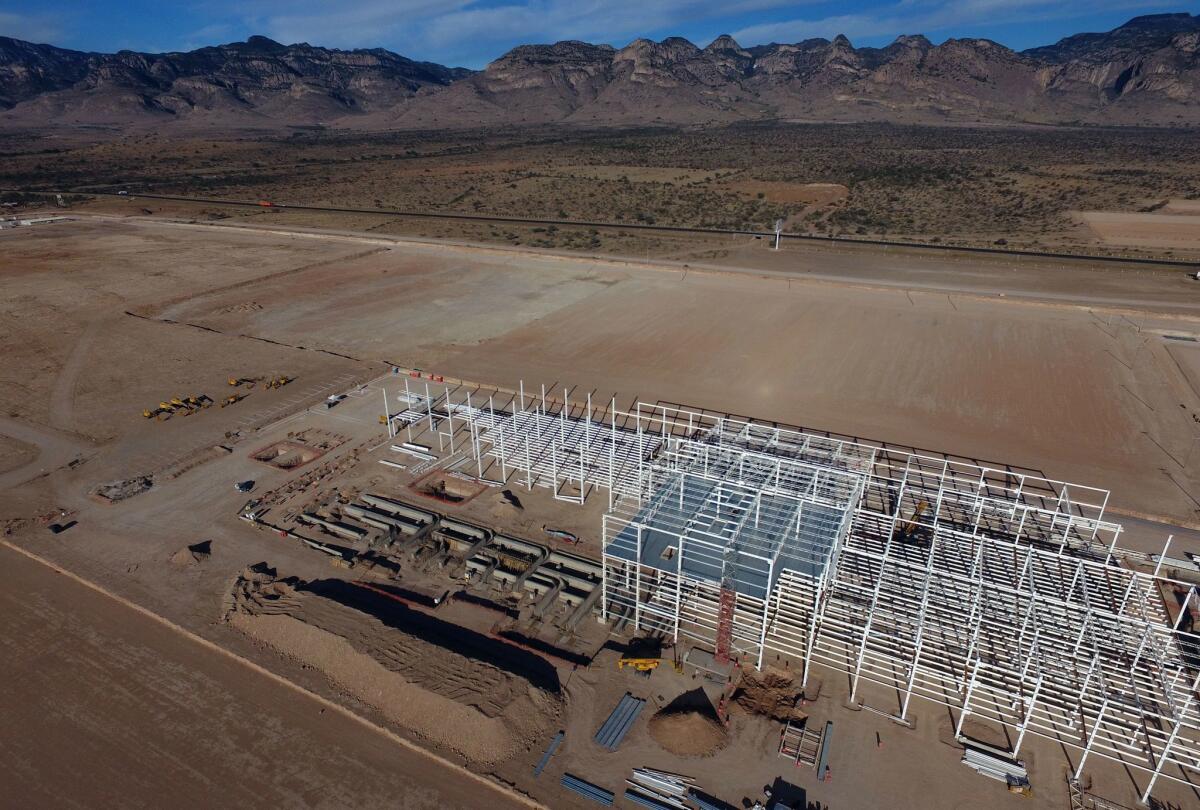

Reporting from Villa de Reyes, Mexico — All that’s left are some dirt tracks, a handful of trailers and a steel skeleton, ghostly remnants of what was once the next big thing in a desert boomtown.

The grand blueprint of a U.S. auto behemoth has given way to this: clearing up the mess, paying off the bills and getting out of town.

For Mexican officials and global automakers, the dispiriting scene — the site of Ford Motor Co.’s now-scrapped plans to build a $1.6-billion factory in central Mexico — stands as the harbinger of a clouded future. The good times of hefty profits based on cheap Mexican labor and tariff-free exports to the United States may be coming to a crashing halt.

Citing a $60-billion trade deficit with Mexico, President Trump has vowed to renegotiate deals and possibly slap a tax of 20% or more on goods imported from Mexico. That would threaten some two decades of steady growth in Mexican manufacturing exports to the United States, spurred by the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The nightmare scenario of an abrupt halt on trade, the region’s lifeblood, has yielded profound disquiet in board rooms from Detroit to Tokyo and here in Mexico. The country’s leaders have bet the house on duty-free exports, mostly to the United States, a strategy that critics in Mexico have long assailed as short-sighted.

Now, Ford’s retreat and the tough talk from Washington stands as a cautionary tale in a new and uncertain era.

“If Trump were here, I would tell him that Mexico is your best commercial partner and your principal ally in the American bloc,” said Gustavo Puente, secretary of economic development for the state of San Luis Potosi.

Many are assuming that Trump’s hard-line stance on tariffs is a tough-talk negotiating gambit. Their hope is that U.S.-Mexico trade talks eventually will lead to a revised trade regimen, probably tilting more in favor of U.S.-made content, but not what they view as a prohibitive new tariff structure that could also cost the jobs of thousands of U.S. workers dependent on the cross-border commerce.

“To close this off now is to shoot yourself in the foot,” Puente said in an interview at the cavernous convention center in the state capital of San Luis Potosi, just north of the abandoned Ford plant in Villa de Reyes. “ You’re hurting yourself.”

Ford insists that slumping demand for compact cars — not a hostile Twitter barrage from the then-president elect — was behind its decision in early January to cancel plans to open the plant here, which was to produce Focus compacts.

Still, Ford’s decision to walk away “was like being drenched by a pail of cold water,” said Gabriel Solis Avalos, mayor of Villa de Reyes, where the 700-acre Ford plant was to be built, employing almost 3,000 workers, not including new jobs for suppliers.

“Everything was agreed upon,” lamented Solis, a construction entrepreneur in Villa de Reyes, a once-sleepy ranching and farming community, now home to a number of massive, post-modern industrial parks. “But we aren’t going to cry about it. We have to move on.”

Last week’s U.S.-Mexico war of words centered on Trump’s insistence that Mexico pay for his “beautiful” wall along the border. But that nasty row was a sideshow for the managerial class in Mexico’s north-central highlands, a mesquite and cactus-spiked expanse transformed into an industrial powerhouse. Here, trade is the big-ticket item on the U.S.-Mexico agenda.

Billboards in English blaring “Land Available” rise from empty lots on the grounds of sprawling industrial zones. One sign implores: “Join Success.” Yet cattle still forage among the endless stands of nopal and maguey.

Yellow company mini-buses disgorge legions of workers in the morning and pick them up in the afternoon. Construction crews hasten to finish factories that resemble airline hangers and complete new overpasses, bristling with rods of rebar, to accommodate the ever-increasing truck traffic rumbling down the roads. Ford may be gone, but General Motors is here and both BMW and Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. are building immense new factories, Trump or no Trump.

Highway 57, which passes by sundry factory complexes en route to the northern industrial hub of Monterrey, has been dubbed the “NAFTA Highway,” after the landmark trade pact that went into effect Jan. 1, 1994, and prompted Mexico to abandon its protectionist trade policies.

Almost a quarter-century later, the results are easy to see in San Luis Potosi and the nearby auto-manufacturing region known as the Bajio, an industrial juggernaut with efficient road and rail links to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Though U.S. firms dominate here, this is a multinational affair. Sizable numbers of Japanese, German, South Korean, French and Italian factories are part of the mix, many producing parts for U.S.-bound autos.

Free-trade backers say export-linked job creation in Mexico has a positive effect on immigration. Many Mexicans no longer have to contemplate sneaking across the U.S.-Mexico border.

“It seems a bit contradictory to want to stop illegal immigration but also be against something that creates jobs for people in Mexico so they don’t feel forced to leave,” said Manuel Lozano Nieto, secretary of labor for the state of San Luis Potosi.

He spoke from his office in the city’s Tangamanga Plaza, where the upper-floor windows offer a glimpse of another side of globalization: a cluster of international chain stores, including Wal-Mart, Costco, Sam’s Club, Best Buy and Home Depot.

That NAFTA has generated employment and some measure of prosperity in Mexico is beyond doubt. Many Mexican workers have moved up the economic ladder thanks to international investment.

Throughout Mexico’s export-oriented industrial zones, new housing developments line the highways of dusty towns-turned-industrial-hubs that churn out cars, refrigerators, air conditioners and other products for the U.S. market.

But not everyone in Mexico is on board with the cross-border strategy embraced by the nation’s economic and political elite. Free trade is as controversial in Mexico as in the United States, perhaps more so.

Critics say NAFTA has fallen short of its promises to lift the Mexican economy, which still suffers from sluggish growth, stagnant wages, rampant inequality and a huge informal sector.

“Free trade made a lot of money for foreign companies and rich Mexicans, but it hasn’t really helped the working classes,” said David Rios, an independent union leader who was among labor activists in the central plaza of San Luis Potosi on a recent evening protesting the layoffs of state workers. “It’s fine with us if Trump gets rid of it.”

The nearby plants have brought new spending power to Villa de Reyes. But residents said that wages for unskilled workers in the factories hardly allow for a middle-class lifestyle.

“Someone is making a lot of money here, but it’s not us,” said Roman Benoso, 24, who was found on a recent afternoon walking beneath a searing sun through the expansive confines of the World Trade Center industrial park.

Benoso, who hopes to finish high school and study to be an engineer, was headed to a German auto-parts company to receive his severance pay. He quit after more than a year on the assembly line to take a better-paying post at a U.S. car assembler. His weekly salary rose from the equivalent of about $50 to $65 —hardly enough, he said, to marry and start a family on his own.

Benoso, who has an uncle in Oklahoma, said he had contemplated heading to the United States to work illegally, following the well-worn path of many compatriots from the region. Ultimately, he decided otherwise.

“With all that’s going on in the north with Trump, I think I’d rather stay here in Mexico,” Benoso said as he made his way through manicured streets lined with box-like factories and a United Nations-style mix of flags fluttering on each side of the road. “I really don’t want to get mixed up in all that.”

Cecilia Sanchez of the Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

ALSO

Mexican drug lord Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman has a new home: The Guantanamo of New York

Families divided by Trump’s refugee order worry about the future

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.