With Afghanistan decision, Obama abandons goal of ending wars he inherited

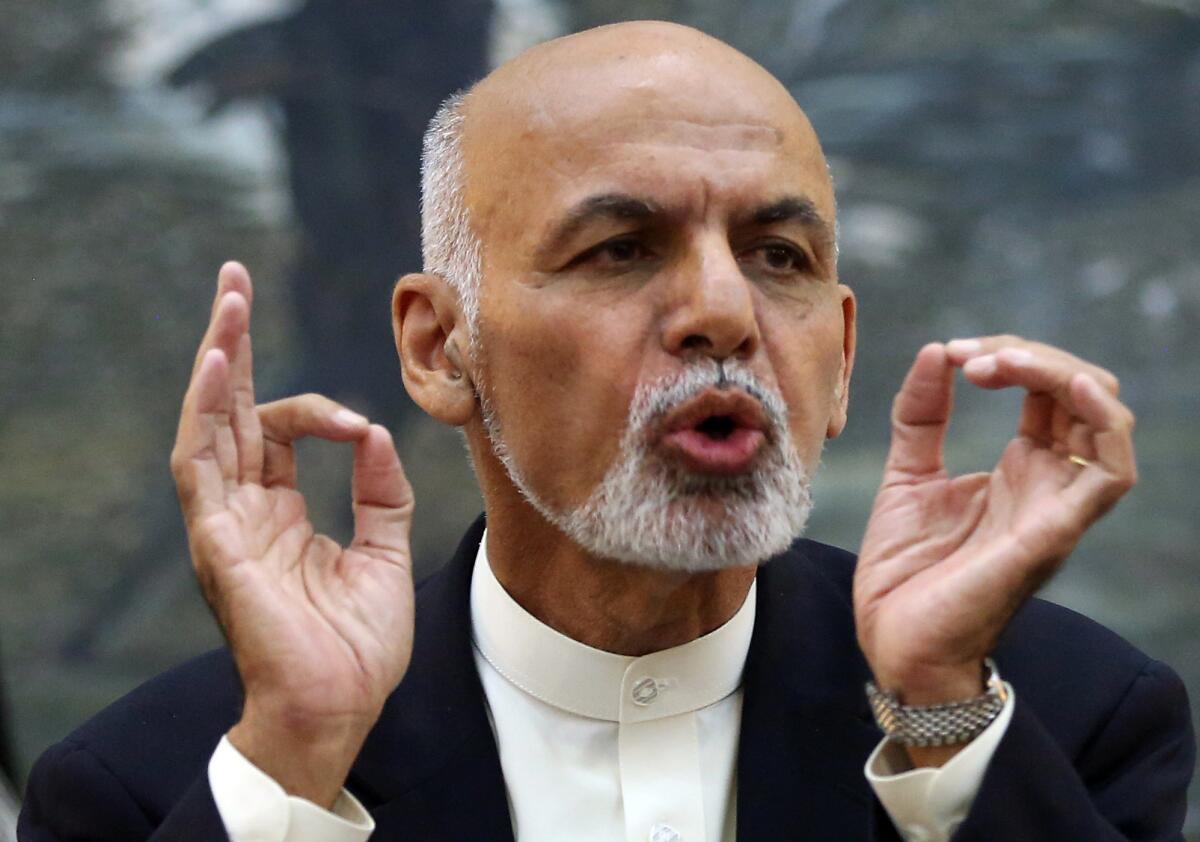

Afghan President Ashraf Ghani warned U.S. officials that a full-scale withdrawal of American troops from his country could severely undermine its security.

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — President Obama on Thursday set aside his last hope of completely withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan, sacrificing a long-desired goal in the interest of avoiding chaos in another former American war zone.

Confronted almost daily with the problems caused by the collapse of U.S.-trained security forces in Iraq, where he has been forced to send additional American troops and warplanes to combat Islamic State militants, Obama was unwilling to risk a similar scenario unfolding in Afghanistan, aides said.

But the decision to keep 9,800 U.S. troops in Afghanistan for most of the rest of his tenure, the number dropping to 5,500 in 2017, means giving up a moment that Obama had hoped to mark before he left office: the end of all but a U.S. Embassy presence in the locales of the two wars he had inherited from President George W. Bush.

After campaigning on a pledge to end the U.S. roles in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, he will hand both over to his successor.

In a White House appearance Thursday, Obama insisted that he was “not disappointed” in the decision, saying he was “absolutely confident” that he was making the right move.

“As your commander in chief,” he said, “I believe this mission is vital to our national security interests in preventing terrorist attacks against our citizens and our nation.”

He emphasized that America’s combat mission in Afghanistan is over, saying that the remaining troops will stick to pursuing potential terrorists and aiding and advising the Afghans. But he acknowledged that American troops are still likely to die in the country, albeit far fewer than during the worst of the fighting — 25 have been killed so far this year, he said — and that in key areas the security situation remains very fragile.

Instead of bringing two wars to a complete close, Obama’s legacy will be a foreign policy doctrine that he hopes will reduce the chance of new ones: his insistence that the U.S. will get involved only in military missions that serve a clear, narrowly defined national interest.

His critics disparage that as undue reluctance to use force, saying that Obama has conveyed a message of weakness to potential adversaries that serves to make the world more dangerous.

Obama’s objectives were clearer and more absolute when he ran for office in 2008, saying he would be the president to lead America out of war.

But as his tenure moves toward its final year, White House officials had increasingly begun to acknowledge that goal would not be achieved.

“It’s hard to be bold at the end of a presidency,” said Jon Alterman, a Middle East specialist with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “When they campaign, candidates want to be clear, and they want to be different. But after almost seven years in office, presidents know how rarely things turn out the way they planned.”

As in Iraq, the situation in Afghanistan had deteriorated by the time Obama inherited it, making the conflict difficult to end, said Gordon Adams, professor emeritus of International Relations at American University. And there’s no evidence that keeping a large U.S. military presence in either country would have brought stability, Adams said.

“But, domestically, presidents get blamed, so, like Bush before him, Obama’s legacy will be tainted by the ‘failure’ to ‘win’ or ‘end,’ these conflicts,” Adams said.

Obama was aware of that as he launched a months-long review of troop needs in Afghanistan, advisors say.

Personally, the president had a lot vested in a full withdrawal. But as U.S. commanders provided weekly reports on the readiness of Afghan forces to secure the country, Obama kept “an open mind,” one advisor said, speaking anonymously to describe the deliberations. Over time, he began to reach the conclusion that fully drawing down would not be possible.

Meanwhile, the security situation in Afghanistan worsened. Late last month, the Taliban captured Kunduz, in northern Afghanistan, the first major city they had controlled since the U.S.-led invasion in 2001. Although government forces have since recaptured the city, the fighting displayed the weakness of the Afghan security forces, despite billions of dollars of U.S. aid and training.

Last week, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter traveled to Brussels to brief NATO allies, and this week, Obama made the final decision.

As the news became public, some critics objected that Obama had not listened enough to the concerns of military commanders. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, hailed the decision to extend the military mission. But he also said he was concerned that the number of troops will not be sufficient.

“The bottom line is that 5,500 troops will only be adequate to conduct either the counter-terrorism or the train-and-advise mission, but not both,” McCain said. “Our military commanders have said that both are critical to prevent Afghanistan from spiraling into chaos.”

In a news conference at the Pentagon, Carter said that the president’s decision enables the U.S. military to “finish what we started.”

“Whatever it takes to protect our country and make sure that Afghanistan doesn’t again become a platform from which terrorism arises, I am confident we will take appropriate action,” Carter said. “I’m confident that future presidents would do the same.”

In Afghanistan, however, though the government controls most major population centers, significant rural parts of the country are controlled by the Taliban and other extremist groups, including the Haqqani network and some militias that have declared loyalty to Islamic State, also known as ISIS. Those groups have significant freedom to move around the countryside.

That presents a stalemate, said Christopher Harmer, a military analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, a nonpartisan public policy group in Washington.

“I don’t look at any of these developments as a legacy, so much as the continuation of a war that the American public should understand will be multi-generational,” Harmer said.

“It took the U.S. 40 years to win the Cold War. The war against radical terrorist organizations like the Taliban and ISIS will take at least that long.”

For more on the U.S. military, follow @WJHenn. For more on the White House, follow @CParsons

MORE ON THE U.S. AND AFGHANISTAN

Pentagon to make ‘condolence payments’ to families of victims in Kunduz attack

Obama apologizes to Doctors Without Borders for Afghan hospital bombing

The night the hospital in Kunduz became a U.S. military target

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.