Islamic State has offered to trade hostages for imprisoned ‘superstar’

- Share via

For months, Islamic State militants have engaged in a high-stakes game of deadly extortion, threatening to behead American captives they are holding in the Middle East unless their demands are met, including an end to U.S. airstrikes targeting their strongholds in Iraq.

But the price tag for the hostages’ freedom has also included another prize: a diminutive, 90-pound Pakistani neuroscientist who studied at MIT before launching into a two-decade relationship with some of the best-known terrorists in the world.

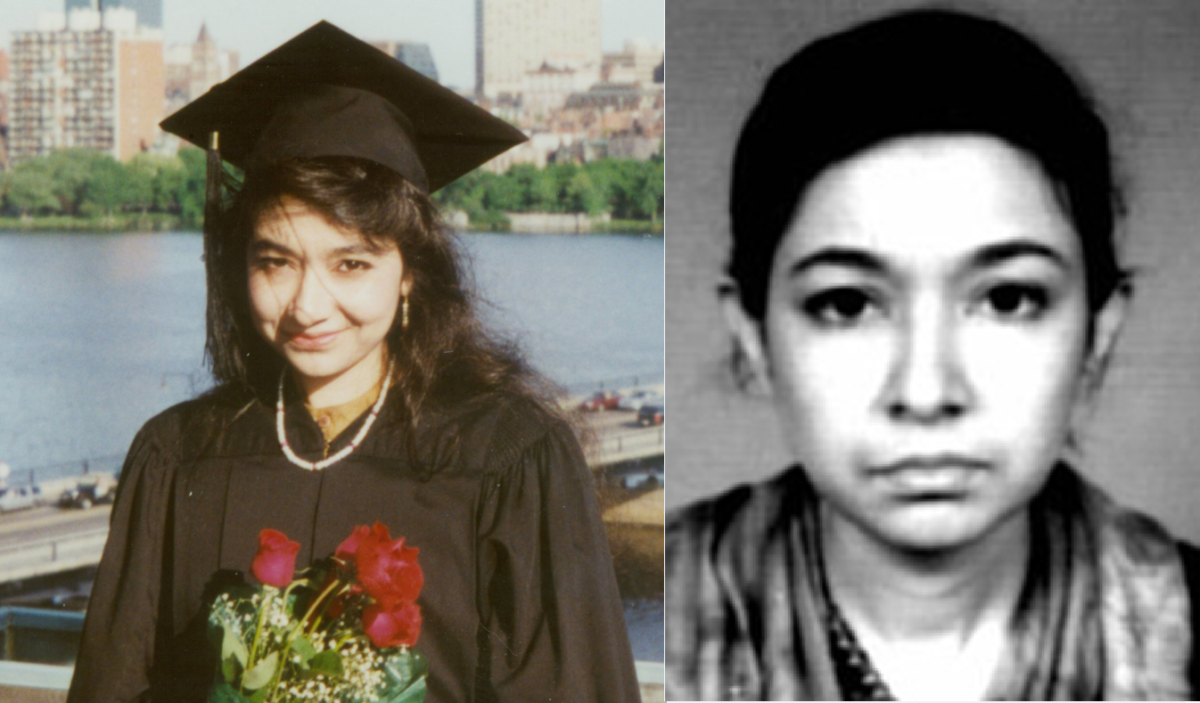

The figure at the top of Islamic State’s want list is Aafia Siddiqui, the wife of a key facilitator of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, and a former employee of the Al Qaeda mastermind who planned them. Siddiqui is serving an 86-year sentence at a federal prison in Texas on her conviction four years ago of attempted murder for grabbing an unsecured rifle and firing on U.S. agents who were interrogating her in Afghanistan.

Siddiqui was arrested in the town of Ghazni in July 2008, having made her way onto the U.S. most-wanted list for her work with Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, identified by the 9/11 Commission as the principal architect of the 2001 hijackings.

But it was her activism with Islamist groups in the United States in the 1990s that first brought her to the attention of U.S. agents. Siddiqui was active with the Muslim Students Assn. and a Muslim charity linked to fundraising for Osama bin Laden while she was studying biology at MIT, later earning her doctorate in behavioral neuroscience at Brandeis University.

Siddiqui’s name as a potential trade for U.S. captives first emerged in back-channel negotiations that led to the release of Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl in May, said Joe Kasper, deputy chief of staff for Rep. Duncan Hunter (R-Alpine), who sits on the House Armed Services Committee.

“On several occasions, both the Taliban and Islamic State have asked for either the release or extradition of Dr. Siddiqui in exchange for U.S. captives,” said Kasper, who has been privy to communications with the militant networks.

Bergdahl, who was captured by the Taliban after reportedly straying from his unit in Afghanistan in June 2009, was released in exchange for five Taliban prisoners at the U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, through the intercession of Qatar, a Persian Gulf emirate with ties to Islamic groups.

Hunter wrote to President Obama last month, after Islamic State executed American journalist James Foley, to say he was deeply concerned by the failure of the U.S. government to consider “multiple non-kinetic lines of effort” within the Pentagon to secure the release of other Americans known to be held in Syria and Afghanistan. He was referring to negotiation and diplomacy, including prisoner exchanges like the one that led to Bergdahl’s freedom.

Kasper said the Pentagon has strategists who are experienced in working with hostile forces and have better contacts and relationships with the captors than do the FBI and State Department, the lead agencies assigned to pursue release of hostages who are not uniformed military. Even in the case of Bergdahl, whom the Pentagon wanted freed before the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan is completed, Kasper said, the U.S. government categorically ruled out any idea of extraditing Siddiqui in return for the soldier’s freedom.

Kasper said that being willing to discuss the option of Siddiqui’s exchange or extradition could be vital to conveying to the captors that their U.S. hostages are valued by the government. Prematurely closing that option also carries the risk that the militants will conclude that their prisoners are most valuable as propaganda, said Kasper, alluding to the grisly, videotaped executions over the last month of Foley and fellow American journalist Steven Sotloff.

Islamic State’s keen interest in freeing Siddiqui also became clear with the militants’ demands to British intelligence recently seeking to free captive aid worker Alan Henning, London’s Daily Telegraph reported Tuesday.

Whether Siddiqui, 42, can be exchanged for U.S. captives without negative consequences is doubtful. Counter-terrorism experts say her “superstar” status in the community of violent Islam would hand Islamic State an enormous propaganda victory. And some analysts say her intimate knowledge of American culture and scientific expertise could be used by terrorists to construct and deploy weapons of mass destruction.

Others, though, describe Siddiqui as a smart but troubled woman who has kept suspect company but poses little security risk.

The woman who repeatedly disrupted her 2010 federal court trial in Manhattan with erratic shouts and accusations also has continued to defy authority in prison. She is in special restricted confinement at the Carswell federal prison in Fort Worth for behavioral infractions, according to court papers filed by her New York attorney, Robert J. Boyle.

At the time of her 2008 arraignment, another attorney representing Siddiqui portrayed her client as someone caught in the net of an overzealous U.S. counter-terrorism campaign.

“I think it’s interesting that they make all these allegations about the dirty bombs and other items she supposedly had, but they haven’t charged her with anything relating to terrorism,” Elaine Sharp said of Siddiqui, who was convicted in a 14-day trial and sentenced to the maximum on each charge related to the assault on her interrogators.

Milton Leitenberg, a University of Maryland professor emeritus and expert on arms control and biological weapons, says Siddiqui may be dangerous in some ways but “she knows zero about biological weapons.”

A Facebook page of the Aid4Syria organization, which raises funds for victims of the war in Syria, is devoted to support for Siddiqui. It urges sympathizers to help “bring her home” and describes her as “far from the media characterization of ‘Lady Al Qaeda.’”

The mother of three figured prominently on the U.S. list of terrorism suspects wanted for questioning after Sept. 11 for her work with Mohammed, who is on trial at Guantanamo with Siddiqui’s husband and three others on charges of mass murder stemming from the terrorist attacks 13 years ago.

Siddiqui married Mohammed’s nephew Ammar al Baluchi while working with them in Karachi, Pakistan, after returning to her home city after her U.S. studies. She went missing with her three children from a previous marriage after Mohammed’s arrest in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, in March 2003.

Although U.S. authorities had her on a most-wanted list, Siddiqui said in court papers that she had been held in secret U.S. detention and tortured for some time during the five years between her disappearance and her arrest on July 17, 2008, in the southeastern Afghan city of Ghazni — an allegation the U.S. government never confirmed or denied.

Her arrest came when she was reportedly “acting suspiciously” outside the provincial governor’s office, prompting U.S. agents who encountered her and her 11-year-old son to detain her. Bomb-making instructions, potentially lethal substances and a list of New York City landmarks, including the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building, were found in her possession, according to documents attached to her federal indictment.

“She’s been associated with a really dangerous jihadist milieu for a very long time,” said Jeffrey Bale, a professor of counter-terrorism and religious extremism at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. He noted that she was tried only on charges related to her attack on her interrogators, but “there was plenty of evidence that she was involved in terrorism plots.”

Since her trial and virtual life sentence, Siddiqui has been seen among some civil liberties advocates in the West as a “victim of mistreatment,” Bale said. In terrorism circles in South Asia, he said, she is more: “She has become not just a heroine and superstar, but a cause celebre.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.