Spanish literature animates the ghosts of its embattled history

- Share via

Reporting from Madrid — For the past month, I’ve been here in Spain working on my next project about my Purépecha grandmother. The connection to this country is that her uncle, my great uncle, relocated with his Spanish employers, who were fleeing the perils of the Mexican Revolution. He was their servant in Michoacán and, circa 1910, he chose to leave his family and the Americas in exchange for Europe. He was never heard from again.

I’ve always been intrigued by this story, and I arrived in Madrid with zero expectations of ever learning his fate. I don’t even have his name. It has been lost after decades of silence and disinterest. Whoever had any reason to remember it is already dead. But what better place to contend with the past than in Spain, a country that continues to reckon with its embattled history and generations of ghosts.

I realize that my search for my uncle is really a search for the stories of immigrants and the children of immigrants.

— Rigoberto González

My book companion throughout this stay is Aaron Schulman’s “The Age of Disenchantments: The Epic Story of Spain’s Most Notorious Literary Family and the Long Shadow of the Spanish Civil War.” It provides a valuable primer on the ways literature intertwined with politics during Franco’s reign from 1939 until his death in 1975. The lens of this story is the Panero family: Leopoldo Panero (1909-62), considered the poet laureate of the Franco regime, his wife and three sons. Panero’s family — his two older sons also poets — enjoyed a period of celebrity long after Panero’s death when a 1976 documentary by Jaime Chávarri placed them back in the spotlight.

Schulman’s opening chapter relates the assassination of the poet Federico García Lorca in 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War. I happened to be in Madrid on June 5, the 121st anniversary of Lorca’s birth. There were commemorations here and there, particularly in Granada, where the casa-museum bearing his name is located. His statue in Madrid stands at Plaza de Santa Ana, facing the Teatro Español, and that day, its arms — lifted up to its chest as it releases a bird — were adorned with a bouquet of purple sage. At one point, a young man stood next to the statue to recite Lorca’s poetry.

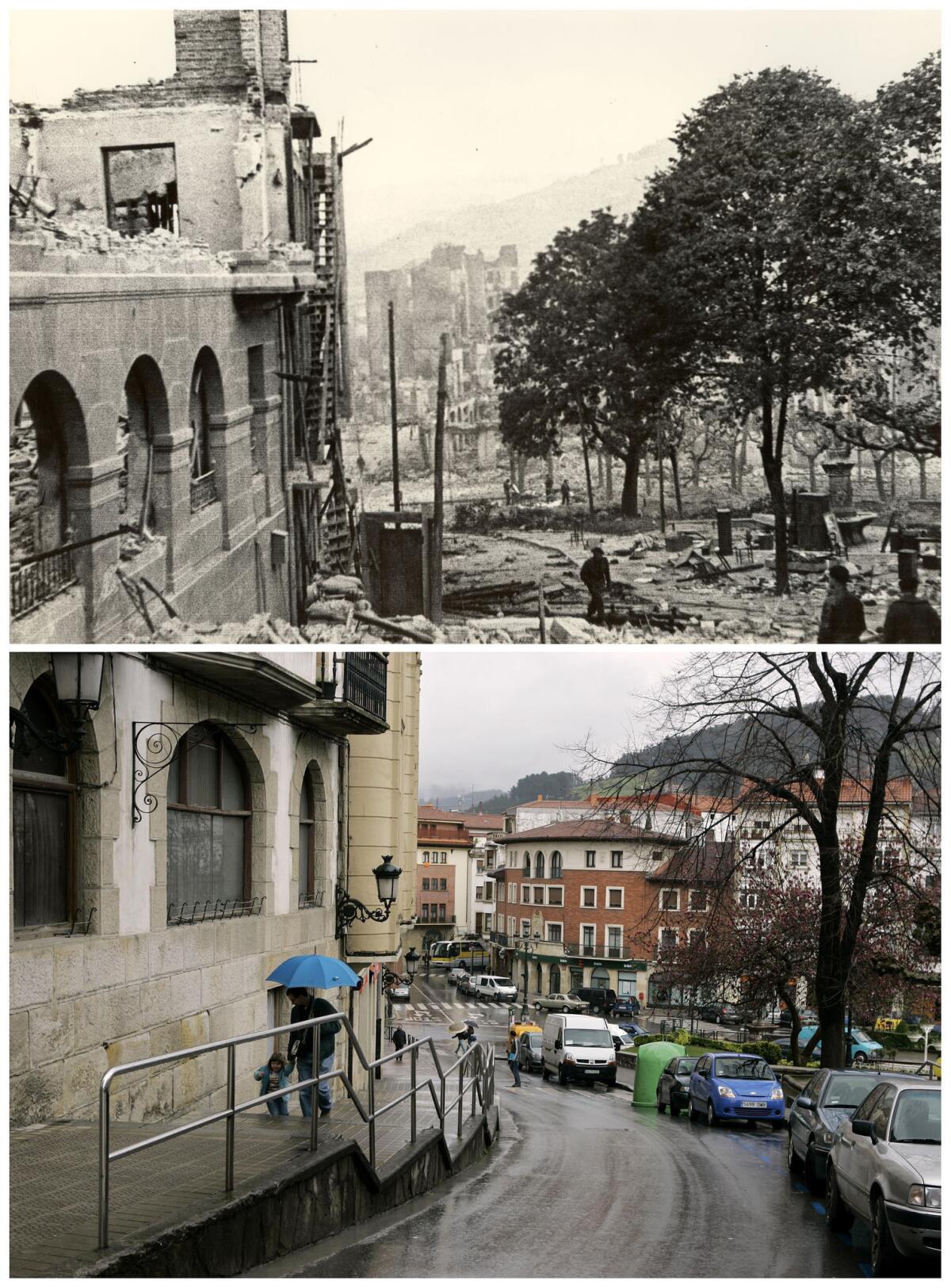

Other than reading his name in Schulman’s book, I don’t hear a peep about Leopoldo Panero, whose loyalty to Franco tainted his reputation. Panero’s own statue, erected in his hometown of Astorga, was eventually decapitated by vandals. But Franco and his lengthy rule will not be forgotten in the work of the writers it affected. The book ushers in a parade of cameos by such literary greats as Pablo Neruda, Luis Cernuda, Vicente Aleixandre, Roberto Bolaño and even Javier Marías, who was a friend of the youngest of the Panero sons and whose father had been briefly imprisoned for opposing Franco. At age 31, Miguel Hernández succumbed to tuberculosis while incarcerated by Franco. But Schulman also reminded me of George Orwell, who joined the Worker’s Party of Marxist Unity to fight against fascism until he was wounded in the throat by a sniper’s bullet. He details this period of his life in the memoir “Ode to Catalonia.” And, of course, Ernest Hemingway was a foreign correspondent in the Spanish Civil War, where he set his novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

Exploring the world’s literary landscapes Rigoberto González

“Reading New Mexico — literature that reveals life at a cultural crossroads”

“In Arizona literature, beauty and conflict collide under the Sonoran skies”

A few contemporary American writers have set their works in Spain, and the results have been quite compelling. Gabrielle Lucille Fuentes’ “The Sleeping World” takes place shortly after the death of Franco and chronicles the uneasy transition from military rule to an age of uncertainty, unaccountability, and unanswered questions — hard truths for Mosca, the young female protagonist discovers as she goes in search for her missing brother. Emma Straub’s “The Vacationers” maps out a two-week stay in Mallorca for an American family who take their emotional baggage with them, straining their holiday and confirming that privilege doesn’t guarantee peace of mind. And Ben Lerner’s “Leaving the Atocha Station,” takes place the year of the terrorist attack on Madrid’s main train station, though the novel first follows the misadventures of an American poet on a fellowship to write about the role of literature during the Spanish Civil War.

Spain ... is a bittersweet fatherland, the empire that forced Catholicism, the Spanish language and its surnames on the Americas through its colonial rule.

— Rigoberto González

For me, Spain is not so much a muse as it is a bittersweet fatherland, the empire that forced Catholicism, the Spanish language and its surnames on the Americas through its colonial rule. The first time I visited Spain, in 2001, my uncle warned me not to walk into the great cathedrals of Spain because they were lined with blood. I didn’t quite understand what he meant until I actually walked into one and realized that all the gold at the altar was from the New World, mined at the expense of indigenous and African lives, not to mention those who might have died constructing the bell towers and apses.

More recently, the populations formerly under Spanish rule are migrating to Spain under a policy that allows citizens from Central and South America, the Philippines, Equatorial Guinea and Western Sahara to obtain Spanish nationality after two years of legal and continuous residence. The economic problems of the world dictate the migration patterns. In recent years, the Venezuelan, Colombian and Argentinian populations in Spain have grown exponentially. There also are asylum seekers arriving on refugee ships, and Spain has been pushed to a limit, and the country is currently reassessing its humanitarian policy. Spain’s conservative party is demanding further efforts to curtail undocumented immigration, particularly from Morocco, a Muslim country.

Rigoberto González’s Spain Reading List

“The Vacationers,” Emma Straub

“For Whom the Bell Tolls,” Ernest Hemingway

“The Sleeping World,” Gabrielle Lucille Fuentes

“The Age of Disenchantments,” Aaron Schulman

“Ode to Catalonia,” George Orwell

“Leaving the Atocha Station,” Ben Lerner

“Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits,” Laila Lalami

One of the first times I dared write a fan letter to a writer was to Laila Lalami, after I finished reading her dazzling debut, “Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits,” a story about a boat carrying Moroccan migrants that capsizes while attempting to cross the Strait of Gibraltar. At the opening, one of its passengers lies dead beneath a sheet. The narrative then unfolds to reveal the lives of those on board; all the while the reader must remember that one of these people will not survive the journey. I wrote to Lalami and expressed how familiar this tale of desperation would be if I substituted the Mediterranean Sea for the Sonoran Desert.

It’s difficult not to think about these issues because they’re all around me as I wander the streets of Madrid. I am renting a flat in La Chueca, where the road and the sidewalks blend so perfectly that tourists like me mistake one for the other. But faces with Latin American features don’t blend, they stand out. My barber Daniel is a 22-year-old from Ecuador. He informs me that his mother brought him here in search of a better life. My neighbors are an all-female family from Honduras. They tell me the same thing. It’s the immigrant condition to always explain one’s distance from home as a way to make peace with the separation.

I hike down to Casa de Campo, a gorgeous park, for exercise every other day. I sit in front of the lake to read or to dine at one of the restaurants, but it’s not until I lose my way one time that I discover that Latin American families also gather in the park on weekends, except they do so in the dusty lots behind the lake and restaurants, bringing with them their own food and music, which they enjoy away from the line of sight of white Europeans.

That evening, I decide to go to the University district to catch a showing of Pedro Almodóvar’s newest film set in Madrid, “Dolor y Gloria,” and later I declare on social media that it’s now my favorite of his films. What I don’t mention, and what startles me, is that Antonio Banderas’ character has a housekeeper named Maya. She is clearly Latin American. I think about my uncle and bemoan the fact that a century later the Latin American body is still cast as the help in the Spanish narrative.

All the while, I realize that my search for my uncle is really a search for the stories of immigrants and the children of immigrants. They are here. I simply need to listen. I attended the first Unamuno Author Festival, where mostly American poets have converged to share their work. At one reading, I was asked to introduce the Filipino American poet Patrick Rosal, who stunned the crowd into silence when he pronounced that, “One day, the greatest living Spanish language poet will be a Filipino. The ones who clean your rooms, serve your food, and care for your children know a lot more than you think they know. I hope the people of Spain are ready when that day comes.”

A few days later I stumble into Parque de Santander, where, in a corner of the park, there’s a statue of José Rizal, a national hero of the Philippines. Flanking the statue are large plaques with his handwritten poem “My Final Goodbye” in Spanish and in Tagalog. I send the pictures to Rosal, whose work I have long admired. At the same park, which has been designed to be a jogger-friendly environment, a Filipina trots along the track. She’s on the phone, conversing in her native tongue.

One week before my departure, I feel more connected to my uncle, who has not disappeared entirely because I am thinking about him. And now I’m writing about him. This is how the people and communities don’t become erased or forgotten. Writers have always known this, which is why they’re so important for any nation’s history — they complete the story and don’t allow it to be dominated by the voice with the most political power.

I take one final walk along Paseo de Prado, where booksellers gather next to the botanical gardens. I find a copy of Juan Rulfo’s “Pedro Páramo.” It takes place in Colima, which borders my home state of Michoacán. This is one of my favorite books because it is about returning home to engage with one’s ghosts. I buy a copy for five euros and sit on a stone bench in the shade to read. About 30 pages in, I decide walk to El Retiro park. The Panero home was located just blocks away on Calle de Ibiza. None of the three Panero sons fathered children. That branch of the family tree has essentially died out. I think about this as schoolkids of various ethnicities scurry through the entrance. They are frivolously chanting the same song, but a few of them — I am certain of this — will find their singular voices as writers.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.