Will your gifted child take calculus? Maybe not under California’s reimagined math plan

- Share via

A plan to reimagine math instruction for 6 million California students has become ensnared in equity and fairness issues — with critics saying proposed guidelines will hold back gifted students and supporters saying it will, over time, give all kindergartners through 12th-graders a better chance to excel.

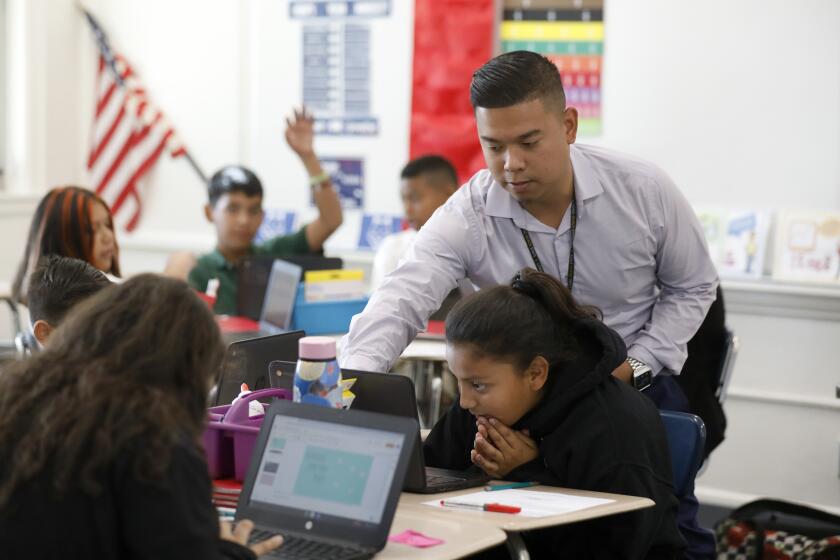

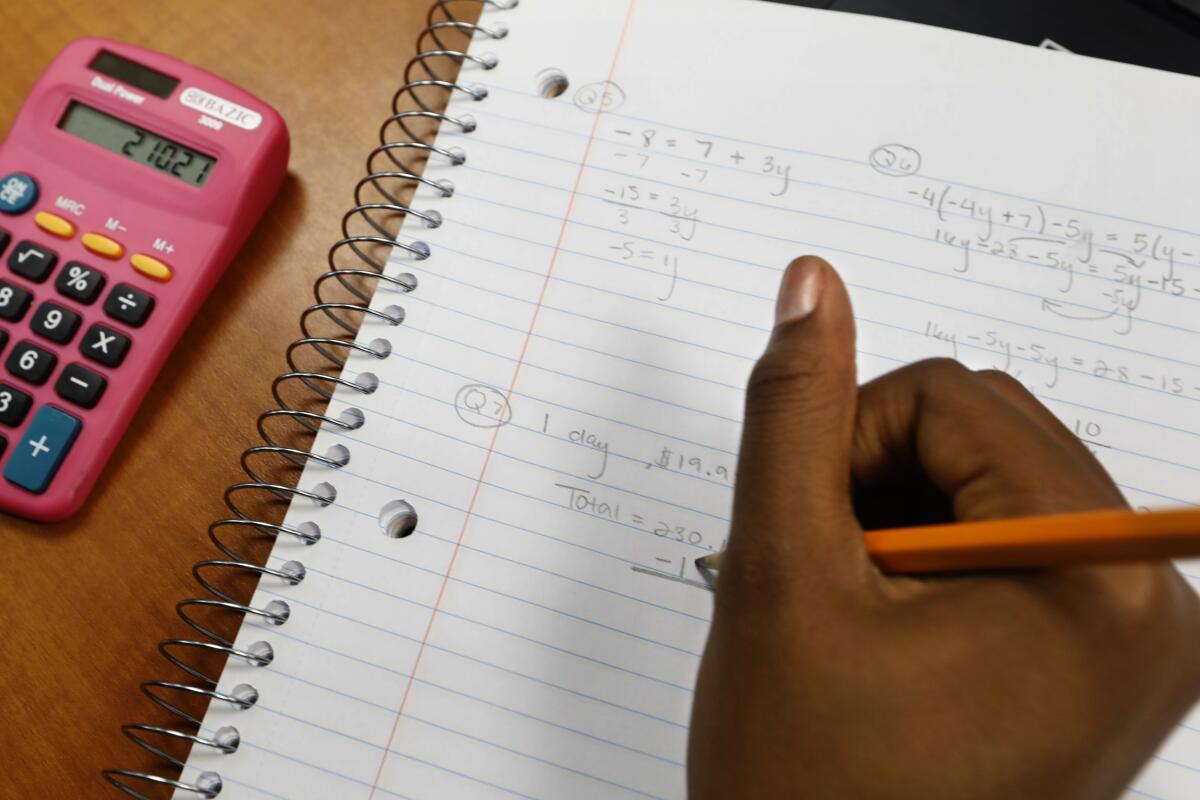

The proposed new guidelines aim to accelerate achievement while making mathematical understanding more accessible and valuable to as many students as possible, including those shut out from high-level math in the past because they had been “tracked” in lower level classes. The guidelines call on educators generally to keep all students in the same courses until their junior year in high school, when they can choose advanced subjects, including calculus, statistics and other forms of data science.

Although still a draft, the Mathematics Framework achieved a milestone Wednesday, earning approval from the state’s Instructional Quality Commission. The members of that body moved the framework along, approving numerous recommendations that a writing team is expected to incorporate.

The commission told writers to remove a document that had become a point of contention for critics. It described its goals as calling out systemic racism in mathematics, while helping educators create more inclusive, successful classrooms. Critics said it needlessly injected race into the study of math.

The state Board of Education is scheduled to have the final say in November.

The new framework aligns with experts who say that efforts to fast-track as many students as possible to advanced math are misguided. And they see their campaign for a more thoughtful, inclusive pacing as a civil rights issue. Too many Latino and Black students and those from low-income families have been left behind as part of a math race in which a small number of students reach calculus.

Still in draft form, the new math framework emphasizes a deep, inclusive approach to learning — possibly at the expense of allowing students to get to advanced work more quickly.

“For a significant number of students, the rush to calculus can have a significant detrimental effect on the necessary deep-level understanding of grade-level mathematics to succeed in subsequent coursework, and districts should be aware of this research to make well-informed choices,” said Brian Lindaman, a member of the math faculty at Cal State Chico and part of a team of heavy hitters from academia who wrote the framework together.

“We are seeking to elevate students and to bring them up,” Lindaman said. “We’re not bringing anyone down. We’d like to bring everyone up.”

Opponents don’t see it that way, especially because the proposed guidance recommends doing away with the tracking of students, suggesting instead that students of all backgrounds and readiness should be grouped together in math classes through 10th grade.

For critics, this approach is a manifesto against calculus, high-achieving students and accelerated work in general.

“This is a disservice to all of our students,” Deanna Ponseti, a teacher at Warren T. Eich Middle School in Roseville, northeast of Sacramento, wrote in comments submitted to the commission.

“About half of my students come to me below grade level, and approximately 25% of them are more than two grade levels below,” she wrote. “Therefore a large portion of my time is spent teaching foundational skills to support the 6th grade curriculum. Even with differentiation, there is not enough time to have deeper level discussions and explore the depth of concepts for the 20% of our students that come to us well above grade level. At the same time, there is not enough time to meet the needs of those struggling students.”

Echoing a nationwide downward trend, most California students are falling short of state learning targets and are not on track to succeed in college, according to the results of new, more rigorous standardized tests released Wednesday.

A parent from Los Angeles called into the meeting to say that the new framework would create two classes of students, those learning at a slow pace in public schools, and those who could afford a more accelerated approach at a private school.

Most of the dozens of speakers during the public hearing were opponents — many of them identifying themselves as parents or teachers of gifted or high-achieving students.

But framework co-writer Jo Boaler, a professor in the Stanford Graduate School of Education, countered that research strongly supports the success of “heterogenous” classrooms. Another co-writer, Stanford assistant professor of education Jennifer Langer-Osuna, described a classroom of the near future where teachers would engage with students at all levels, so that everyone would feel challenged.

Calculus and other high-level math, they insisted, were not under assault.

State Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), who sits on the commission, challenged whether that ideal was readily achievable in the typical California classroom. He also questioned the suggestion that tracking by math readiness was inevitably racist. He noted that in the Los Angeles Unified School District nearly all are students of color. So, he asked, how then would it be racist to track some L.A. Unified students into faster-moving coursework if they are ready for it?

He abstained on the vote forwarding the draft to the state Board of Education, emphasizing that he supports addressing past inequities while providing opportunity and deeper math understanding for all students.

State Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond said an underlying goal of the framework is simply to modernize math education.

“Part of what’s going on in the framework is an attempt to bring mathematics education into the 21st century, in terms of what kind of mathematics kids get opportunities,” Darling-Hammond said in an interview. “The old [way], the idea that calculus is the capstone, is one that originates with a committee of 10 men in 1892.”

When did you last divide a polynomial? High schoolers deserve math instruction relevant to their lives, rather than algebra and other higher math.

A key element is elevating data science, which for many students is likely to be more valuable than calculus, added Darling-Hammond, who hasn’t yet had an opportunity to review the framework in detail.

Some of the opposition has focused on a document cited in the framework: A Pathway to Equitable Math Instruction. In an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, Williamson Evers, a former U.S. assistant secretary of Education, said the document was representative of a move toward subjective answers to math problems, watering down the curriculum and needlessly racializing the science of math.

“This program is quite a comedown for math, from an objective academic discipline to a tool for political activism,” he wrote.

In their work, the Pathway authors wrote, “Teachers must engage in critical praxis that interrogates the ways in which they perpetuate white supremacy culture in their own classrooms, and develop a plan toward antiracist math education.”

The commission ultimately followed the advice of the analysts from the state Department of Education, who counseled that they remove references to the Pathway tool kit.

The reason, they said, was that the Pathway material was still being revised close to the time of the meeting and the department had lacked sufficient time to fully vet the tool kit in its final form.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.