Here’s how California’s bold plan to change math instruction could help or hurt students

- Share via

California is preparing to overhaul the way math is taught to 6 million kindergarten through 12th graders, the first major changes since 2013.

Here are essential elements of the draft Mathematics Framework, which is drawing scrutiny from educators and parents across the state:

What are some key features of the plan?

A major element of the framework emphasizes grouping students with different levels of preparation through the 10th grade. So, instead of putting the most accomplished students together to accelerate their learning, these students would be dispersed among regular classes.

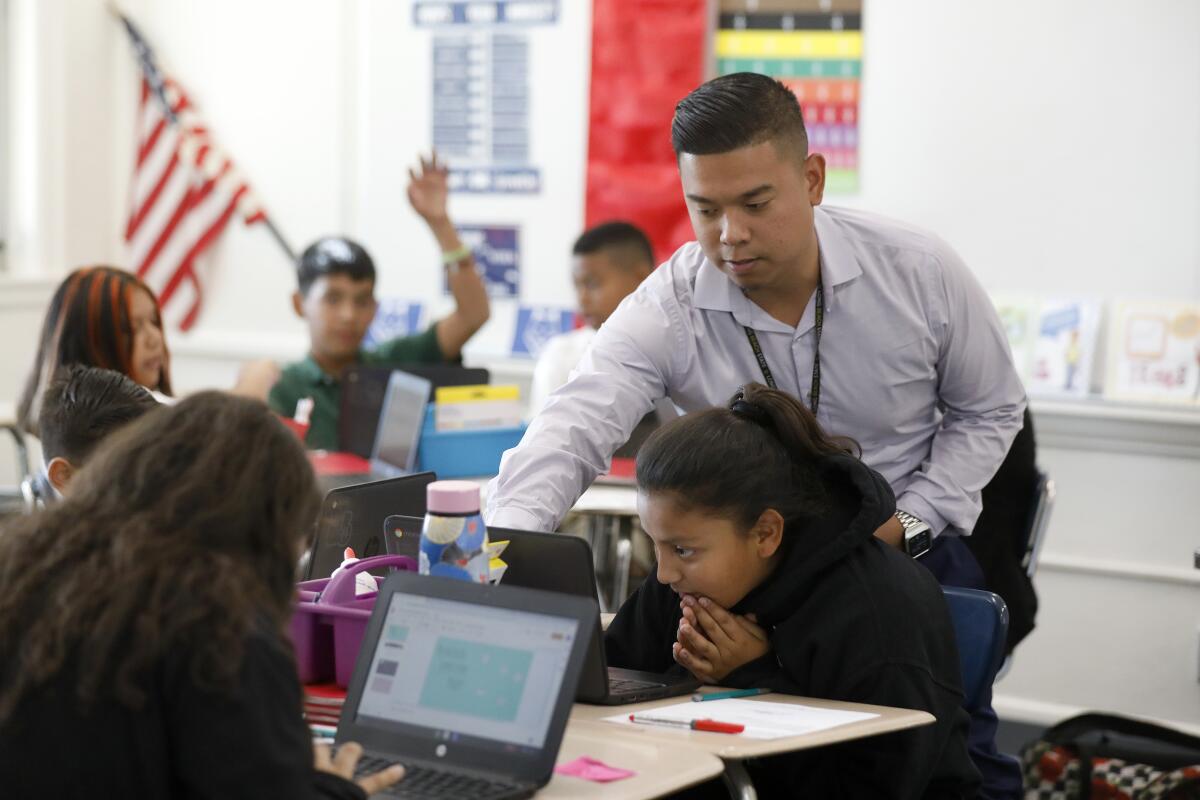

The academics who wrote the framework say such “heterogenous” groups will function more effectively than such classes in the past. Students, for example, might be learning about the same “big idea,” but they would approach it at their own level. The teacher would challenge the more advanced students with more complex work. This is called differentiated instruction and, to some degree, it happens all the time in class.

Supporters say this structure opens the on-ramp to advanced math at all times to students with unrealized potential. But others worry that well-prepared students will be held back — rather than progressing appropriately at their more advanced level.

The framework also builds on the state’s existing push toward integrated math, which sets aside the traditional sequence of math instruction: computation, algebra, geometry and ultimately advanced algebra, trigonometry and calculus. Instead, concepts from all areas are introduced early on and brought together to solve problems — as might happen in a real-world use of math.

In addition, the framework emphasizes pathways in advanced math that lead to subjects other than calculus. Instead, students could aim for statistics and data science, which most are more likely to use in their careers than calculus.

How would this new approach work in an actual classroom?

The draft framework offers “vignettes” of these practices in action — and members of the state’s Instructional Quality Commission have asked the writing committee to add more for further clarity.

One vignette presents to students the problem of balancing the survival of endangered bowhead whales, decimated by commercial whaling, with the needs of a native population that has relied on hunting whales for food, economic sustenance and cultural traditions.

Students must develop a plan that would allow hunting while also permitting the whale species to survive and thrive. The variables with mathematical components would include the growth rate and life cycle of the whale and the food yield and economic impact of the hunt.

Critics say California’s proposed math framework waters down content in pursuit of equity. Defenders say social awareness will accelerate learning.

Commissioners suggested that the mathematics could be deepened further by bringing in variables related to climate change, which could affect whale fertility and food sources as well as migration patterns.

While the exercise was designed for high school students, it could be adapted to younger grade levels — or to less mathematically adept students within a class. Students could work for mathematically derived solutions individually or in groups.

The writers also suggest that individualized learning — such as a student working independently on a computer — could allow for advanced students to move faster than classmates.

Math is fundamentally an objective science. Why have racial issues been brought into an instructional framework?

The traditional math sequence and teaching practices have worked well for some students, but math-related fields continue to be dominated by white males, supplemented by workers who learned math in other countries or who grew up in a family or culture that emphasized math attainment.

In the Los Angeles Unified School District, only 24% of 11th graders scored as proficient in math on state standardized tests in 2019, the most recent test given. The district’s enrollment is 74% Latino and 8% Black; 80% of students qualify for subsidized meals because of family poverty.

The proposed framework declares war on low achievement with a math-for-all premise.

“All students deserve powerful mathematics,” the guidelines state. “We reject ideas of natural gifts and talents ... and the ‘cult of the genius.’”

And the fault for low math attainment lies with structural inequities, influenced by racism and sexism, according to the framework.

“The subject and community of mathematics has a history of exclusion and filtering, rather than inclusion and welcoming,” the framework states in Chapter 1. “There persists a mentality that some people are ‘bad in math’ (or otherwise do not belong), and this mentality pervades many sources and at many levels. Girls and Black and Brown children, notably, represent groups that more often receive messages that they are not capable of high-level mathematics, compared to their White and male counterparts.”

What do the critics say?

They fear the new approach will limit opportunities for gifted and well-prepared students to reach advanced math, and that, once they do, there will be less time for them to master advanced concepts. Some argue that tracking, as long as it’s not used to exclude students by race, ethnicity or gender, can put students in groupings where their individual needs can be addressed most directly, allowing all students to learn faster.

Another concern is that many top colleges still place an emphasis on whether applicants get to calculus and how well they do in that course.

Some critics also worry about math being watered down or instruction being dragged astray by political beliefs.

Is the new approach the law of the land? Will my school and school district have to do things differently?

Not yet. The Instructional Quality Commission has asked for revisions. When they’re done, a second public comment period will begin. The state Board of Education could take up the 800-page document as soon as November.

Once approved, the guide is not mandatory — and it explicitly allows the old course sequence leading to calculus to continue. However, the guide’s preferences, including for non-tracked classes, will influence teachers, school districts, teacher training and curriculum publishers. And it would be challenging for schools to offer both the old way and new way.

Don’t students need calculus and other high-level math to get into the most selective colleges?

That is an issue, although an increasing number of colleges are putting data science or statistics on par with calculus. With college admission tests like the SAT and ACT no longer required for the University of California and falling out of favor at some other colleges, admissions officers are increasingly turning to other benchmarks to evaluate applicants. Performance in Advanced Placement math courses will still be considered in college admissions, as will the rigor of courses and grades.

I thought that math reformers want to get more students into higher-level math sooner. What happened to the push for eighth-grade algebra?

In 2008, state officials decreed that all students needed to take algebra by eighth grade — if not sooner — because all students needed access to the high-level math track. In fact, the state’s rating system for schools was affected by what percentage of students made it to algebra by eighth grade.

At the time, advocates called the early algebra imperative a civil rights issue, similar to the language being applied today toward a strikingly different approach.

Now there are experts — including those involved in writing the state’s draft framework — who discredit that algebra push. They say that pushing higher-level math at an unprepared student can turn that student off from the subject. They also say a rush through mathematical concepts deprives all students of the deeper understanding they need to succeed in advanced curriculum.

They also question the goal of reaching calculus or at least reaching it as quickly as possible.

The move toward and away from eighth-grade algebra is one of many examples of pendulum swings in education-improvement efforts. Generally, there are committed supporters behind a range of strategies, each able to cite research to back their preferred direction.

It’s too early to tell if the math framework’s major elements will be widely accepted or if the pushback will be broad and forceful.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.