- Share via

As record rainfall inundated Southern California last week, the scene at the mouth of the Los Angeles River in Long Beach was dramatic.

The flow of water was ferocious — some 65,000 cubic feet per second at the terminus of the L.A. River’s flood control system. That’s like 65,000 basketballs going by, every second, that are filled with water and weigh 62 pounds apiece, said Los Angeles County public works director Mark Pestrella.

Even more impressive was that for all the rain — nearly 9 inches over three days, the second-wettest three-day period on record for downtown Los Angeles since recordkeeping began in 1877 — the L.A. River was just at one-third of its capacity.

It could have easily handled a much bigger storm.

All that rain caused scattered, localized mudslides that damaged homes — including one shoved off its foundation — and closed roads.

But L.A. so far has avoided the massive flooding, earth movement, property losses and deaths that came with monster storms of California’s past.

It’s a reminder that a century of extensive, and at times controversial, public works projects have lessened the flood threat, but not erased it. As climate change brings more extreme weather — drought followed by deluges — Southern California will have to grapple with keeping flood defenses strong while dealing with some of the ecological, sociological and environmental damage the concrete system has caused.

Los Angeles County flood control network withstands punishing rains -- for now

Ghosts of 1938

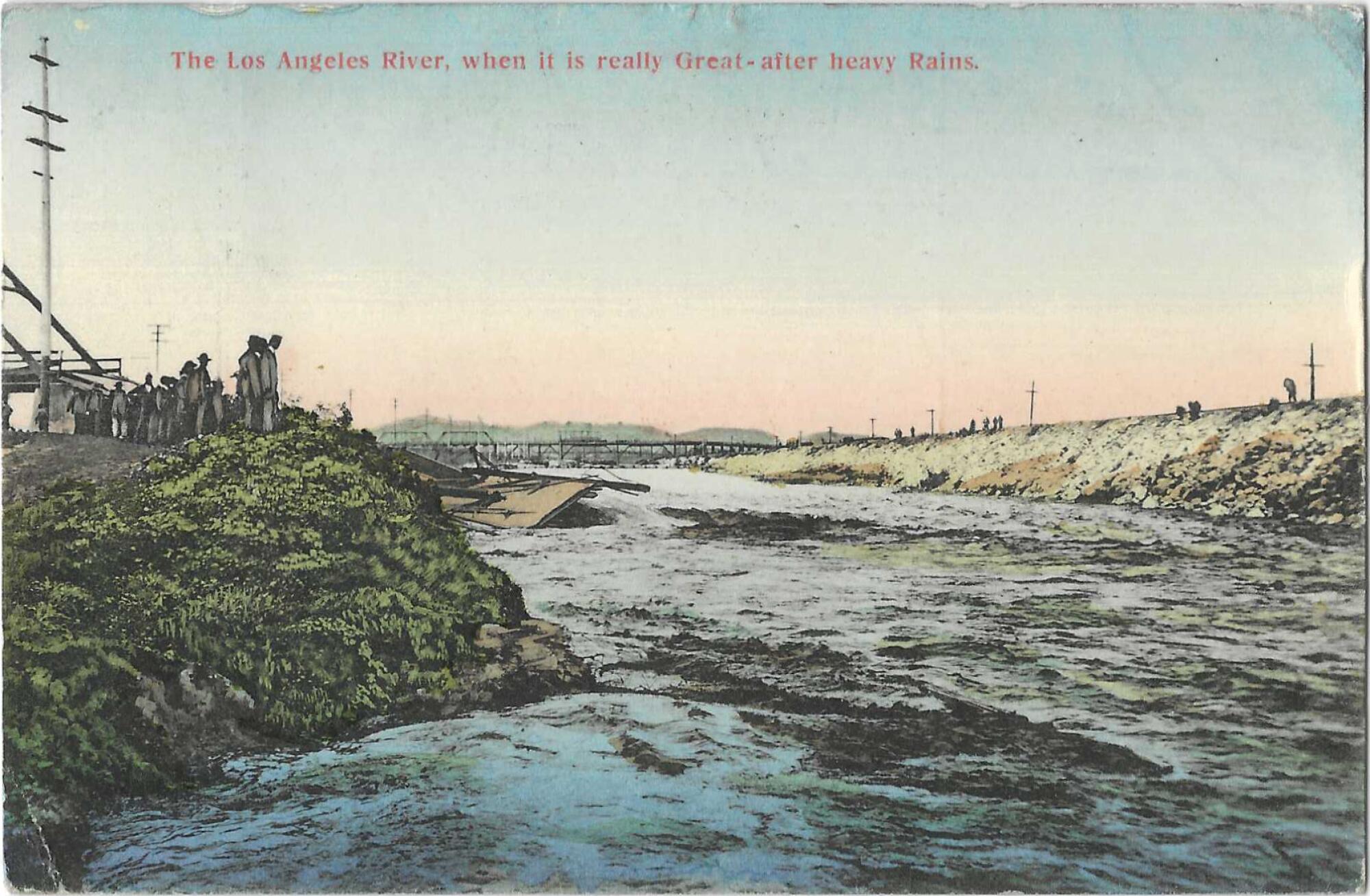

The fact is that massive, fatal flooding has been a part of life in Southern California — forgotten in dry periods, but always looming as each winter arrives.

And in the last century, none was more deadly and influential on flood control policy than the great storm of 1938.

A pair of storms dumped 9.21 inches of rain on downtown L.A. between Feb. 28 and March 2, 1938. The last big day was the worst: 5.88 inches, the all-time one-day record for downtown. And the deluge followed weeks of “almost continuously and frequently heavy rainfall,” according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The floods not only hit L.A., but also struck the five-county region, with as many as 210 people reported dead or missing. Many had little warning about the incoming floodwaters, including those along the Los Angeles and Santa Ana rivers, until it was too late to escape.

For the L.A. River, the 1938 flood broke everything in the historic record, and nothing has come close since. Across Southern California, floodwaters inundated some 450 square miles of the five-county area — basically equal the size of the city of Los Angeles — submerging homes in the San Fernando Valley and washing away the body of an Anaheim mother still cradling her baby, who was found a mile from home.

The history of occasional heavy rain hasn’t disappeared in the modern era. And Los Angeles’ extremes play a role in the ongoing fight to manage flood risk.

The tallest points of L.A. County, the San Gabriel Mountains, rise more than 10,000 feet above sea level, yet a drop of rain falling there has to travel only about 40 miles, as the crow flies, to return to the ocean — meaning there can be precious little time to drain significant water back out to sea.

In this regard, “we have the steepest terrain in the United States,” said National Weather Service meteorologist Joe Sirard, with mountains that tend to “squeeze out that much more rainfall.”

By contrast, a drop of rain falling at the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota travels only 1,500 feet to sea level at its mouth in Louisiana and has more than 2,000 leisurely miles to get there.

That means during the heaviest of storms, L.A. can have torrential rains that are in a rush to get out to sea. And a history of flooding is embedded in our landscape.

So free-spirited was the Los Angeles River in its natural state, its path to the sea twisted and turned. Sometimes, it actually drained via Santa Monica Bay, by way of what is now downtown L.A., Mid-City and Culver City, through Ballona Creek and Marina del Rey.

Other times, the river’s path was not well-defined, with water spreading over a broad floodplain in which “the sediment would fill in and it would dry out,” waiting for the next flood to cut through sand and gravel again to carve a new path to the sea, Pestrella said.

The general path of the L.A. River as known today was carved in 1825, after a big flood cut a new route across a plain of wetlands and forests, according to the county, into what is now Long Beach, which was originally marsh.

Once the fight ended over where the region’s deepwater port would be built — the federal government picked Long Beach/San Pedro over Santa Monica — the Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with choosing the permanent location for the mouths of the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers.

“It couldn’t keep switching around and moving if you were going to start to generate all this commerce” after building the port, said Jon Sweeten, a senior engineer in reservoir regulation at the Army Corps of Engineers’ Los Angeles District.

That would be one of many key moments in efforts to put human controls on the L.A. River as structures were built all over the floodplain.

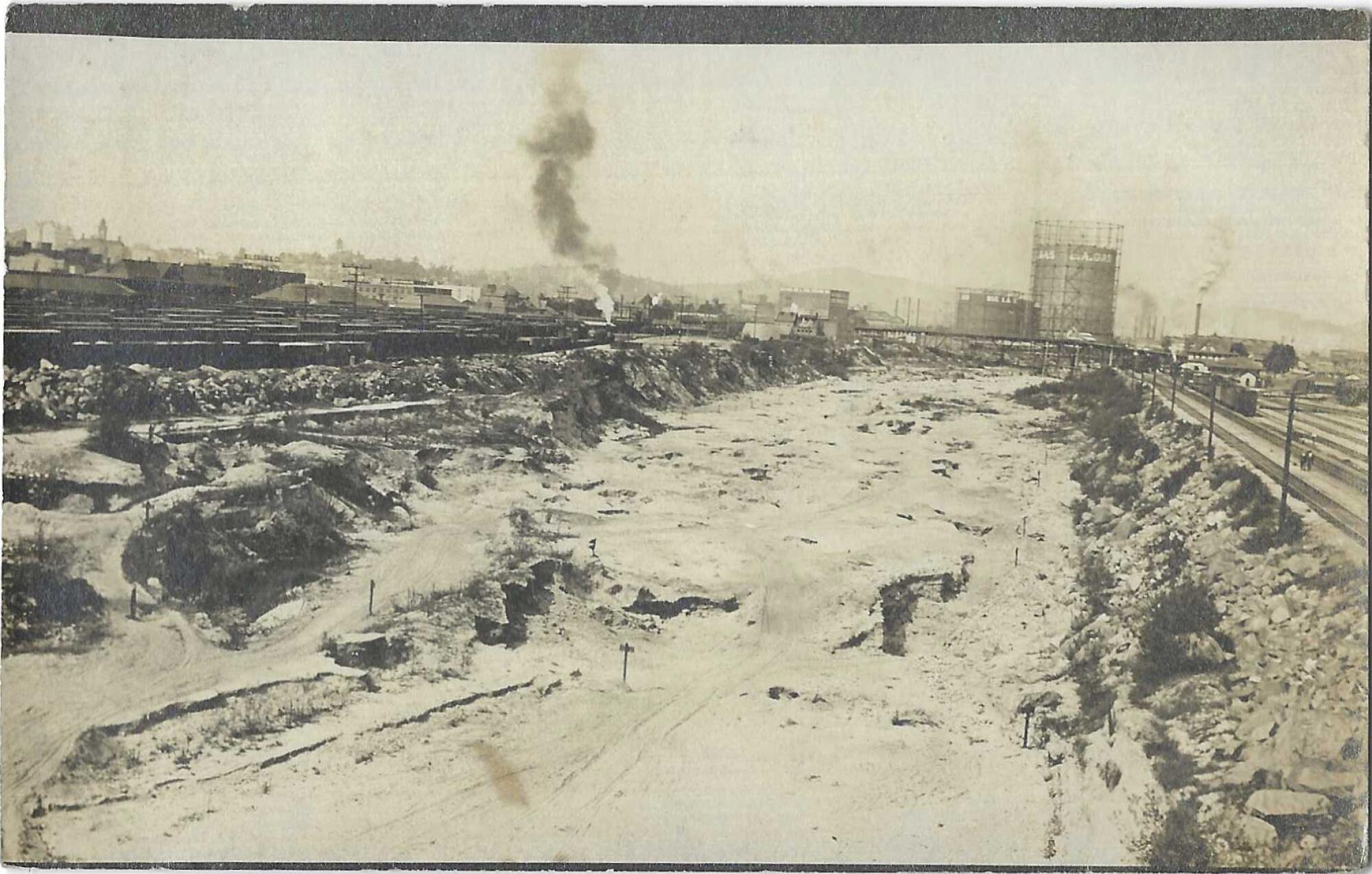

Major floods in L.A. County in 1914, 1933–34 and 1938 proved decisive in generating more support in flood control measures, culminating in efforts to transform the L.A. River into a concrete-lined waterway, with its main goal to expel as much floodwater during storms as quickly as possible.

Capturing rainfall is only one part of the L.A. River’s job. It is also a flood control channel that is critical to protecting lives and properties when stormwaters surge.

Trying to tame the river

To understand why the L.A. River was designed without a lick of nature requires some context. Plans were developed in the era of the building of the Hoover Dam and a sense that “if we poured enough concrete, we could control nature,” Sweeten said. Also, the nation was in the depths of the Great Depression, and there was a hunger for jobs that came with big government-backed public works projects.

“And, you have locals who are saying, ‘Please don’t build a mile-wide river — because we’d have to build bridges across it. And that’ll cost us a fortune,’” Sweeten said. “So they wanted the narrowest rivers that we could build,” which came with the added economic perk of more land to develop, including space for railroads.

Hence, the river was designed with brutal efficiency. The physics of water flow are such that “if you can make the water go really fast, and keep it all going in a straight line, you can convey a lot of water very efficiently,” Sweeten said. But any time the water hits turbulence, whether dirt, rock, trees or other vegetation, “it takes a lot more space to convey the same amount of water.”

With this latest storm, some residents fretted how the normally dry river with a relative trickle from treated wastewater suddenly grew to a torrent, with some fearful it was close to overflowing. But the river worked exactly as intended, Pestrella said. The county’s half-dozen or so “storm bosses” worked long shifts, manning switches at the dams, deciding when to keep water to save for storage (capturing 10 billion gallons) and when to let it go downstream to reduce flood risk.

Learning from past tragedies

One reason L.A. survived last week’s deluge relatively well is that officials learned from past mistakes, notably by cleaning basins that catch mud and debris before they could spill onto hillsides and homes.

L.A. County was in a much better position given its successful clearing out of 1.7 million cubic yards of sediment from the enormous basin behind Devil’s Gate Dam in Pasadena — a massive concrete barrier and last line of defense against floods. Had that not been done between 2018 and 2021, and regular excavations conducted since, last week’s storm would have forced officials to release a full-to-the-brim reservoir through the dam’s spillway, Pestrella said.

Had there been no cleanout, the sediment would’ve been so high by now, the dam’s release valves would’ve clogged, and officials would’ve been helpless as floodwaters rushed over the spillway, resulting in an uncontrolled flow downstream along the Arroyo Seco.

“There would have been some form of flooding of — for sure — the 110 Freeway; there would’ve been a release to the L.A. River, which could’ve affected the L.A. River’s ability to control the flows; and there would’ve definitely been some flooding in South Pasadena,” Pestrella said.

The cleanout was controversial more than a decade ago, with some neighbors and nature enthusiasts initially opposing it, upset about the loss of trees and other vegetation being torn up to clear room to store fast-moving mud falling from the mountains during rainstorms. County crews have worked on habitat restoration since the excavation.

Officials say more needs to be done in other areas. There’s an acceleration of sediment behind other dams from increasing wildfires. Work gets underway during the dry season to remove such sediment from major dams such as Cogswell, Pacoima, San Gabriel, Santa Anita and Tujunga. It’s urgent considering that, as the climate changes, the same amount of water can fall in a shorter period.

Southern California rain totals from the last five days topped 14 inches in some areas, easily besting the average for the entire month of February.

All this means that it’s impossible for every drop of rainfall that falls in Los Angeles County to seep into the groundwater safely during an event like last week’s storm. Even a dramatic expansion of dams and reservoirs to hold all that water to save would still require releasing floodwater to the sea, Pestrella said. Critics say there is still a lot more officials can do to save water.

Officials learned the grim consequences of a lack of adequate storage capacity when the 2018 Montecito flood killed 23 people.

After a devastating fire season, intense rains hit the Santa Barbara County coastal town hard, overflowing creeks and causing massive mudslides. A Times investigation in 2018 noted that a contributing factor to the mudslides was officials failing to thoroughly empty debris basins before the rains, as well as not heeding decades-old warnings to build bigger basins.

Other factors behind the high death toll included conflicting evacuation instructions, worse-than-expected rain and residents who were skeptical about calls to evacuate.

But no flood control system is perfect. New Orleans experienced widespread inundation when levees failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

An epic flood, on the scale of California’s economy-killing 1861–62 floods, would put swaths of Los Angeles and Orange counties underwater. A series of such storms would overwhelm defenses along the region’s three mightiest rivers — the Los Angeles, San Gabriel and Santa Ana. Stretches of Long Beach, southeast L.A. County and much of northern Orange County would be underwater, according to a scenario by the U.S. Geological Survey.

People might say, “‘Nah, we’re never going to get a big flood here again’ — that’s not really true. It’s perfectly capable” of happening, Sweeten said.

The future of the river

The river also has a complicated legacy. In the county’s master plan, officials note that “for Indigenous Peoples,” the river’s design “comes in the form of multiple generations of displacement and cultural erasure.” In addition, certain neighborhoods were marginalized, including along the lower L.A. River, which runs next to the 710 Freeway.

There has been a growing effort in recent decades to reclaim the river from blight, including the addition of improved recreational facilities such as bike paths and parks along its banks.

Next to the Rio de Los Angeles State Park, there are plans for cleanup and development of more parcels of the old railyard once owned by Union Pacific Railroad and its predecessors — Taylor Yard — southeast of Atwater Village. Now owned by the city and state, the plan is to create a park that would reach closer to the river’s edge and add “riparian and upland habitat” next to the river, said Deborah Weintraub, the chief deputy city engineer and a senior architect for the city’s Bureau of Engineering.

It’s adjacent to a rare “soft-bottom” section of the L.A. River called the Glendale Narrows, where trees and vegetation have grown over the years and some river enthusiasts kayak. Originally, that section was not covered in concrete because of the high water table there; it was instead lined with big stones at the bottom, with concrete sloped walls. Over the years, the stones trapped silt and seeds and eventually palm trees and other vegetation grew under the rocks, trapping more sediment and returning some nature to that section of the river, Sweeten said.

The storm fed off of unusually warm waters as it grew. It also reached “bomb cyclone” status as it neared California.

Some have proposed removing some sections of concrete from the river and restoring it to its natural habitat.

This idea, as promoted by Friends of the L.A. River, would involve “strategic and safe concrete removal in designated areas in order to allow biodiversity to return to the river in order to allow plants to grow, allow trees to grow, and allow birds to return and animals to be in the river,” said the organization’s chief executive, Candice Dickens-Russell. “What we advocate for is for engineers and hydrologists to look at the river and think about where the best places to make those strategic, safe concrete cuts would be.”

But finding those spaces seems to be a challenge. One report considered an option to widen the river at the old railyard, but officials concluded it couldn’t be done “because it would increase flood risk,” Weintraub said. “Right now, there are no plans to take any concrete out of the river in that stretch.”

A different report discussed terracing the river upstream from that spot — changing the sloped shape of the sides into steps, “and in those steps, you might insert areas for landscaping to grow,” Weintraub said. But further study would be needed to determine whether that could be done without worsening flood risk.

There’s also the L.A. River Master Plan, which includes a controversial concept by famed architect Frank Gehry to install “elevated platform parks,” built on concrete planks and girders, high above where the Rio Hondo and L.A. River meet in South Gate. Gehry also concluded it would be unsafe to remove concrete from the river.

His ideas, however, were opposed by groups interested in a more natural river. “We are not ready to give up on the river,” Dickens-Russell said. “We remain dedicated to biodiversity on the river.”

An idea not widely seen as feasible by engineers is removing all of the concrete along the entire river. Doing so would displace tens of thousands of people and upend dozens of miles of freeway, more than 100 bridges and scores of miles of transmission lines, under one scenario calculated by the county.

Had the river been designed today, efforts to retain more natural spots could have been made. But that would’ve meant a wider span.

“You can’t rewind the tape of history,” said Jon Christensen, environmental historian with the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. “People are right up against the river. You can’t widen it without affecting people and businesses.”

Our complex relationship with the L.A. River is that, when it’s raining, there’s intense focus on its ability to provide flood protection coupled with despair over flushing rainwater out to the sea. And when it’s dry, there’s interest in a year-round waterway that is “tame and fun and approachable, and we want more of that — even though the river in its natural state, before it was encased in concrete, was rarely, if ever, like that,” Christensen said.

“We need to get better at having a more complicated conversation about all of the things that the river needs to do — do for us, and do for the environment, and do for other species.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.