How the score is the driving element behind ‘Babylon,’ ‘a musical without being a musical’

- Share via

Damien Chazelle and Justin Hurwitz are one of the more exciting director-composer pairings of the new century — a millennial corollary to the likes of Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann or Steven Spielberg and John Williams. They’ve known each other since playing in a band together at Harvard, and Chazelle has always given Hurwitz an outsized role beginning with their early musical, “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench,” and through the music-centric films “Whiplash” and “La La Land.”

So Hurwitz was surprised to learn only recently — at a Q&A — that the director had been developing his idea for “Babylon” for the last 15 years.

“He was hiding it from me the whole time,” Hurwitz said dryly on a joint Zoom call.

“There’s lots of work that goes on in the background before Justin gets to swoop in and do his little piano demos,” Chazelle said, ribbing his friend. The director explained how he’d been slow-cooking this epic tragicomedy about the transition from silent films to talkies but that he felt ready to tackle it only a few years ago after doing a ton of research into the era. “But I thrive in that kind of invisible toil to help prop up Justin’s career.”

Theirs is a brother-like relationship — Chazelle is older, but only by three days — intimate and needling, mean and funny, and it pays off in dividends when they make a movie together. Once again, Chazelle knew music was going to be a driving, critical element in “Babylon.”

Damien Chazelle’s new film focuses on actors struggling to make the transition from silent film to sound. We chatted with experts about the real history.

“It was always going to be what it is, which is a musical without being a musical,” he said. “I always thought of it as a party movie, so that means there’s a lot of diegetic music, and the diegetic music winds up being in dialogue with the non-diegetic music, with the underscore.”

He was inspired by “La Dolce Vita,” Federico Fellini’s 1960 saga of Italian decadence where Nino Rota’s music bleeds back and forth from in-world parties to the outside soundtrack. Likewise, “Babylon” blurs the line between what is traditionally considered diegetic or “source” music, and what is score: characters will be dancing — or snorting mountains of cocaine — to a tune being played by a live jazz band one minute, then accompanied by a variation of that same tune in Hurwitz’s off-screen score the next.

It’s a game the duo has been playing since “Guy and Madeline,” in which one of the main themes is introduced in the orchestral overture, and then that melody is heard being played by a busker on the street. In “La La Land,” Ryan Gosling’s character plays a tune on his piano that then becomes a primary theme in the score.

“It’s just something we love doing,” said Hurwitz, who has scored films only for Chazelle and is therefore able to spend several years on each project as an essential creative force.

When they sat down to plot “Babylon” in the fall of 2019, Chazelle’s script was already filled with such directions as: “Sidney plays a fast, uptempo number here. And then the song stops. Now something quieter begins.” Hurwitz took those prompts and started writing, essentially, a long party playlist — one that included wild jazz charts for coke-fueled orgies, stomping numbers with primeval chanting and more down-tempo ballads for the wee, hangover hours.

In line with the other departments, he used materials (in this case, instruments) from the Roaring ‘20s era but infused them with a spirit that was more modern rock ‘n’ roll or even rave culture. Several pieces are riff-based, jams you might expect to hear on a distorted guitar but here played by unison horns “to have that really muscular feel,” Hurwitz said. “But because it’s played with the instrumentation of a [1920s] band, it kind of lives a little bit in the ‘20s.”

With 120 sets to create, Florencia Martin leaned heavily on L.A.’s “kaleidoscope of architecture.”

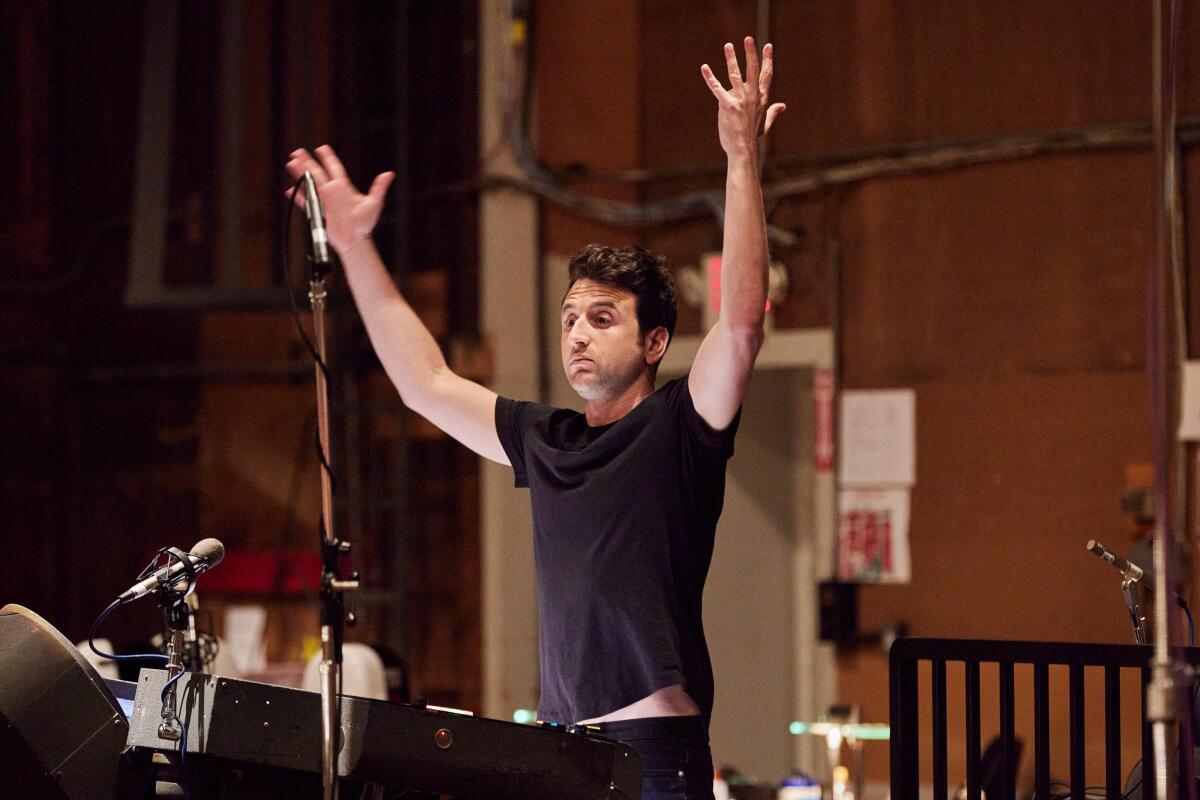

He wrote acrobatic, high-octane solos for a baritone sax player named Leo Pellegrino and a trumpeter, Sean Jones — both discovered through YouTube. More crackerjack soloists and small ensembles were recorded at Capitol Records, and a full orchestra at Sony. As much as anything, the score is a love letter to melody and live musical performance.

Detailed demos were recorded before the film was shot, played back on set like a musical, then sweetened or manipulated after production.

Then Hurwitz took the tunes from these dance pieces and turbo-jazz charts and sneaked them all throughout the score: One became a wobbly love theme for aspiring producer Manny (Diego Calva) and ascendant movie star Nellie (Margot Robbie), another a melancholy motif for the aging matinee idol Jack (Brad Pitt). The melodies were arranged in a wide variety of styles, and it’s never quite clear if they’re coming from a source inside the movie or if they’re “score.”

It’s the kind of holistic, fully integrated soundtrack that only happens when a composer is involved from the beginning, working with a director who foregrounds music. Hurwitz’s tracks drove the rhythms and cadence of the film “almost entirely,” Chazelle said, serving as a “blueprint” for him and editor Tom Cross.

And even though some of the music changed during the final editing stage, “just to have something to kind of guide you ... I don’t know,” Chazelle said, “I would sort of feel lost without it.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.