How to cover the protests? For L.A.’s top Black radio hosts, you make noise, and listen

- Share via

When radio personality Kurt “Big Boy” Alexander first watched the video of George Floyd’s killing, the host of the popular “Big Boy’s Neighborhood” morning show on hip-hop station Real 92.3 (KRRL-FM) could pinpoint the moment he knew his next day’s show would be different.

“Once they took his lifeless body and put it on a stretcher,” he recalled late last week, “I knew immediately that whatever I had scheduled for the next show was thrown out the window. It was going to be totally erased.” Sensing a tense weekend, the station interrupted Saturday programming and Big Boy, 50, went live to take calls.

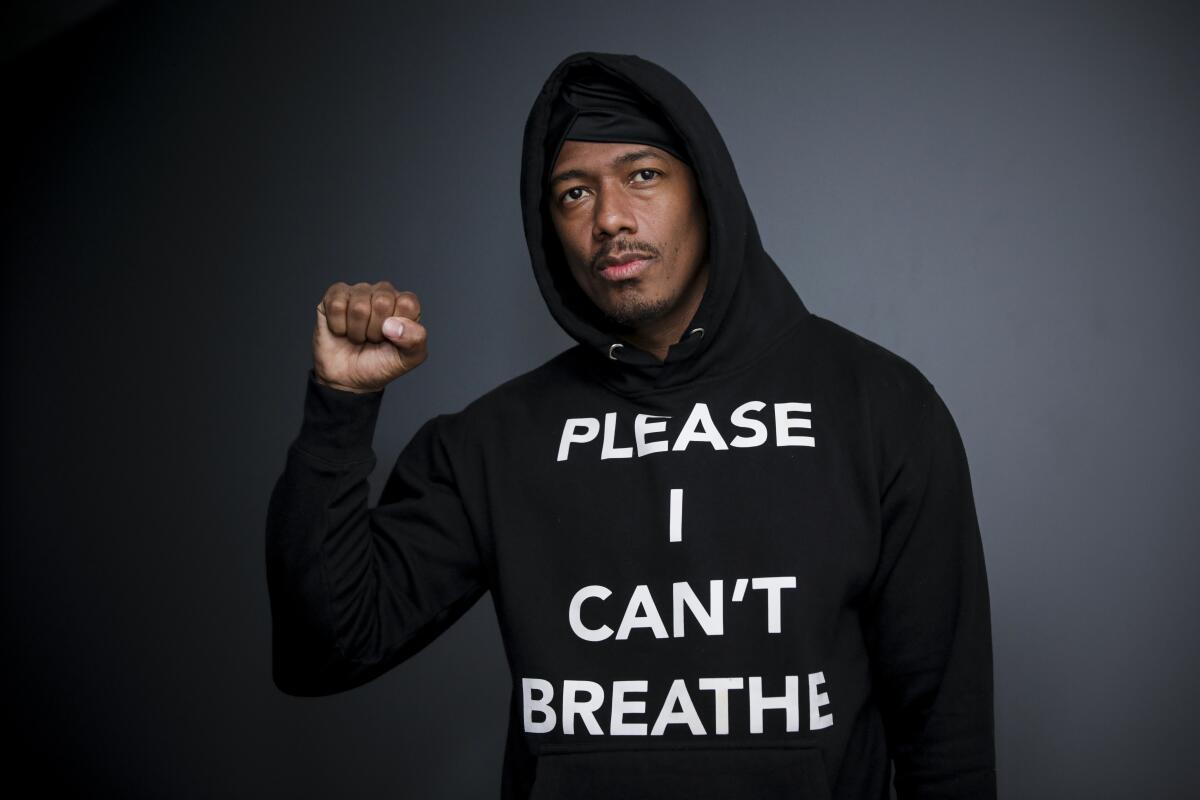

On the other end of the dial on rival Power 106 (KPWR-FM), morning show host Nick Cannon, 39, watched enough of Floyd’s “public lynching,” as he called it, and spoke about it on that Friday’s show. But behind the scenes, he was plotting.

“I wanted to be on the front lines, ground zero, in Minneapolis,” Cannon said earlier this week, so he boarded a plane. By the time he got on the air Monday morning, the scene on the ground in Minneapolis was tense. Images of law enforcement violence against protesters spread across social media.

Demeaning caricatures of Black people have been a sad mainstay of consumer products. It’s time for them to go.

Since that fateful Memorial Day, Cannon, Big Boy, KDAY’s Cece & Romeo, KJLH’s Dominique DiPrima and other Black voices on the FM dial have responded with a kind of communal outrage, in the process reconfirming the platform’s role in the L.A. media landscape. In a culture balkanized by social media, cable news, streaming services and podcasts, terrestrial radio has stepped up in its role as a local forum.

Black radio on-air personalities have grilled guests, discussed racism and police violence, frustrations and solutions. Illustrating the power of the medium, they have broadcast interviews with leaders including Mayor Eric Garcetti, Congresswoman Maxine Waters and Sen. Kamala Harris. On stations including Power 106, KDAY 93.5 and Cali 93.9, programmers increased rotation on what it described as “music that had more conscious messages.” More important, programming blocks have been given over to listeners so they can vent and share.

“You can talk to people a million miles away, but here you’re talking to people rolling down Main Street or Crenshaw and they’re hearing about their neighborhood and their councilpersons in real time,” says historian and curator Daniel Walker, professor at El Camino College. “Terrestrial radio is making these things very real for people, and continuing that tradition, especially for African American-centered or African American-owned stations.”

He added, “Being able to channel that energy and to listen and to respond — those notions are so different than somebody getting 8,000 comments next to a tweet. You’re being heard because, during that time period, you’re the singular voice.”

Over at urban contemporary station KJLH (102.3 FM), veteran DJ Lawrence “Lon McQ” Williams knew he’d address his audience after watching footage of Floyd’s death. During the 1992 L.A. uprising, he and station general manager Karen Slade were part of a team broadcasting the events from the station’s then-studio on Crenshaw. The coverage earned the station, which is owned by Stevie Wonder, a Peabody Award.

Nearly 30 years later as he commuted to the station’s Inglewood studios for his 10 a.m. time slot, McQ pondered what he’d say during the first on-air break. “Do you try to say something profound, or something smart or something spiritual? What do you say?” He opted for an invite. “The first word out of my mouth was, ‘I’ve seen the video. I know how you feel. I know you’re angry. But before you do something rash, call me. Let’s talk about it.’”

The phones lighted up, McQ recalled. “Call after call after call after call, it was basically the same fury, the same anger.”

Added Big Boy of the listener response to Floyd’s killing: “You saw outrage. You saw anger. You saw people that were ready to stand up and do something for whatever cause it was, and it wasn’t just about black and brown. This time it wasn’t people saying, ‘That doesn’t affect me.”

Historian Walker was listening. “For a person from a totally different generation than the young people who are his primary listeners, Big Boy is really speaking to the people you see in the protests, part of that multicultural, diverse swath of America.” Walker adds, “he has that ability to speak to Latinos, Asian Americans, whites, in this kind of California flow that we have.”

That’s one reason why Real 92.3 FM owner iHeartMedia hired Big Boy away from Power 106 in 2015, Walker said. It also proves how much value the stations place on its morning talent. His move prompted a lawsuit by Power 106’s then-owner Emmis Communcations. Big Boy’s contract with iHeartMedia is reportedly worth more than $3.5 million annually.

For his part, Cannon, who just celebrated his first anniversary as Power 106’s morning host — a slot occupied until 2015 by Big Boy —has continually opened the phone lines and invited listeners “to protest live on air.” He’s talked with policemen and their spouses, disenfranchised voters, incarcerated men. During an interview with Gov. Gavin Newsom, Cannon, who recently earned a criminology degree from Howard University, said he had “lost all faith and hope in law enforcement.” In response, Newsom acknowledged the legitimacy of Cannon’s cynicism and pledged to do better.

Asked whether he was satisfied with that response, Cannon said that “from his position as an outstanding politician, I was. One thing I cannot negate about our governor is his ability to present his platform and his rhetoric in a very buttoned-up and smooth manner.” Added Cannon, “He took blame where he needed to take blame, and he said to hold him accountable.”

Cannon said many of his peers were stumped when he decided a half-decade ago to get a degree in criminology. Already a noted actor, comedian and host, the San Diego native earned mainstream attention during an eight-season run as host of NBC’s “America’s Got Talent,” as well as for his since-ended marriage to Mariah Carey. Cannon currently hosts “The Masked Singer” on Fox. As his TV career has flourished, Cannon has become an on-the-ground activist in Black communities.

“I didn’t want to be another so-called entertainer or celebrity having an opinion about something that I hadn’t thoroughly studied,” he said of his degree. “The only way to make change in the system is to know the system from within.” Cannon did ride-alongs with law enforcement and sat down with prison guards, so that “I could speak intelligently on the issues and understand why certain laws are created, and why we uphold certain laws.”

Asked if his opinions had ever drawn the ire of his bosses, Cannon laughed. “I have in the past. I think they know not to mess with me now. They know I stand firm in my beliefs.”

An illicit dance party, held in a South L.A. warehouse on Friday night, may have been the city’s first live music event since the coronavirus shutdown.

Most famously, in 2017 Cannon bumped up against institutional power when NBC lawyers threatened his job at “America’s Got Talent.” During his Showtime comedy special, “Stand Up Don’t Shoot,” Cannon referenced NBC, he recalled, “in a joking manner, but still said something that they weren’t too happy with. I said, ‘NBC stands for N— Be Careful.’”

NBC brass threatened to fire Cannon if he didn’t edit out the joke. He was furious. The show was on a different network. He saw it as a 1st Amendment issue. “For them to threaten my employment — I’ll never forget that moment because I said, ‘They can’t fire me. I quit.’” He never looked back. Recently, Cannon released an incendiary spoken-word video that addressed police violence and civil unrest. He didn’t hear a peep from Meruelo Media Group, which owns Power 106, KDAY, Cali 93.9 and 95.5 KLOS.

Walker called the clip “so strident that you would think that it was somebody who has no ties to any corporate structure, who doesn’t have to worry about the next paycheck or the fact that they also do mainstream television.’”

He also noted that unlike the newcomer Cannon, Big Boy’s 26 successful years on Los Angeles radio has proven his ability to speak both for and with his listeners. “He has a credibility that I think the listeners require of him. His audience expects him to speak to the direct thing, whether it’s gang members, when things are going on like that, or some celebrity feud.”

Most prominently, Big Boy’s June 3 interview with Snoop Dogg went viral after the Long Beach icon made a surprising confession, one couched in a critique of President Trump. “I ain’t never voted a day in my life, but this year I think I’m gonna get out and vote, ‘cause I can’t stand to see this punk in office one more year.”

Asked about that interview, Big Boy said he figured Snoop had at least voted for Barack Obama. “But when he said that he felt like he was brainwashed into thinking that he couldn’t vote because of his [record], I figured we were talking to a lot of people” who [also] thought they couldn’t vote because of a past conviction. Since that interview, local voting initiatives have popped up to address that misconception.

For McQ, such ground-level interaction and communication provides opportunity for an idea exchange that, despite it coming from so-called old technology, breeds trust in his listeners. “I know where they are. They’re in Leimert Park, South L.A., South Central, Long Beach and Compton.” He adds, “A lot of people have moved out to the I.E. — to Ontario, Riverside, Palmdale.”

When it’s their turn to speak over the airwaves, McQ adds, “I don’t try to interrupt them. I don’t try to correct them. I can’t let them say certain things, just the expression of anger at being left out and mistreated, disrespected year after year after year. I don’t try to say whether they are right or whether they’re wrong. I just basically say, ‘Hey, I understand what you’re going through because we all are in this together.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.