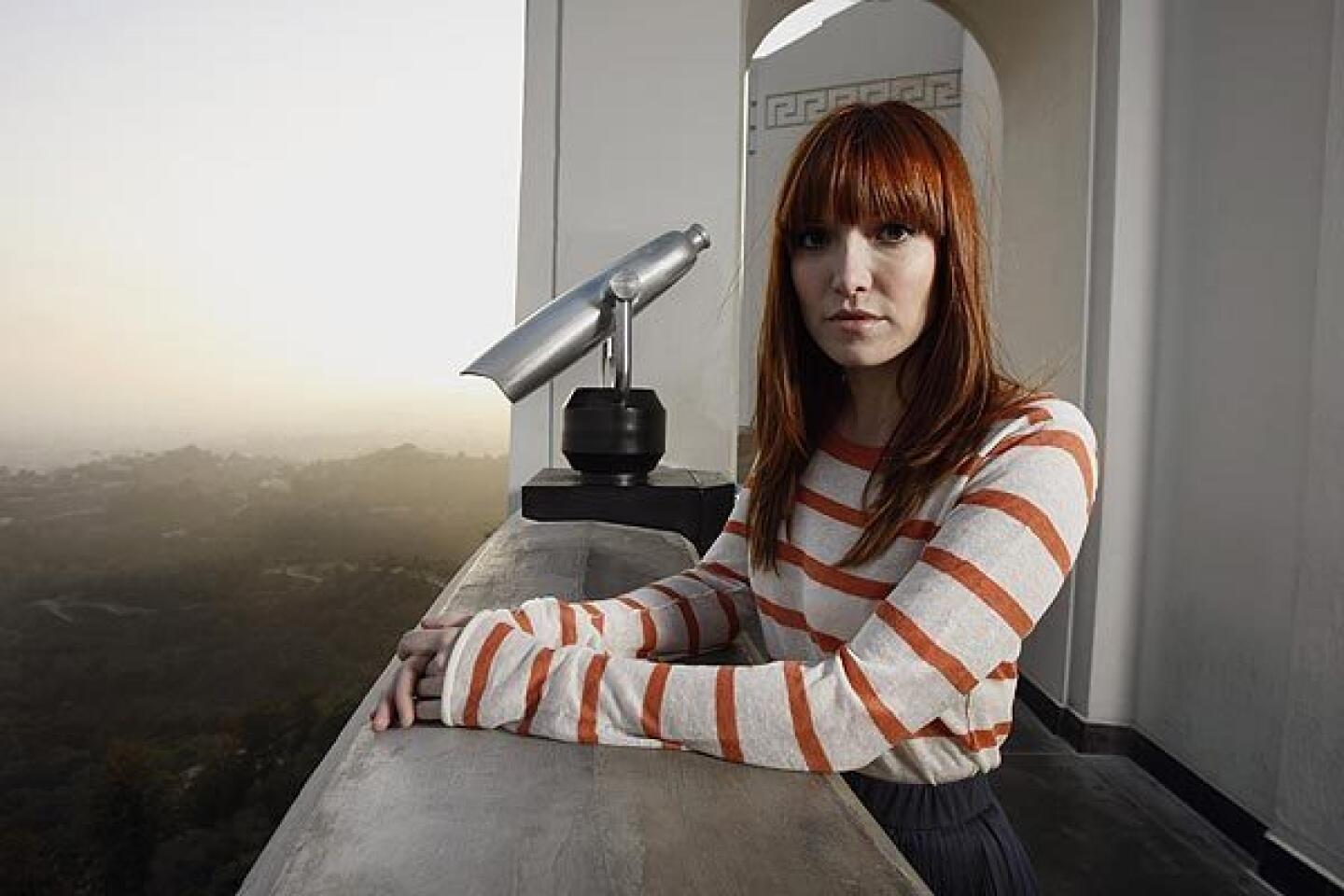

In the moment with Cate Blanchett

- Share via

On the surface, Cate Blanchett would seem to be the least Chekhovian human being on the planet. No idle longing for Moscow for this international stage and screen star, whose frequent flier mileage must have broken the million mark since she and her husband, writer Andrew Upton, took over the Sydney Theatre Company in 2008 and became intercontinental barnstormers.

Yet there she is, this paragon of professional fulfillment, garnering raves at home and abroad for her performance in Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” as a trophy wife who has backed herself into a domestic corner by marrying a cranky codger professor.

The play, which opens July 21 at the Lincoln Center Festival in New York, is a symphony of unrequited love and unrealized dreams — a succulent irony given that the marquee name for this production is a woman who could easily be the model for a “having it all” campaign.

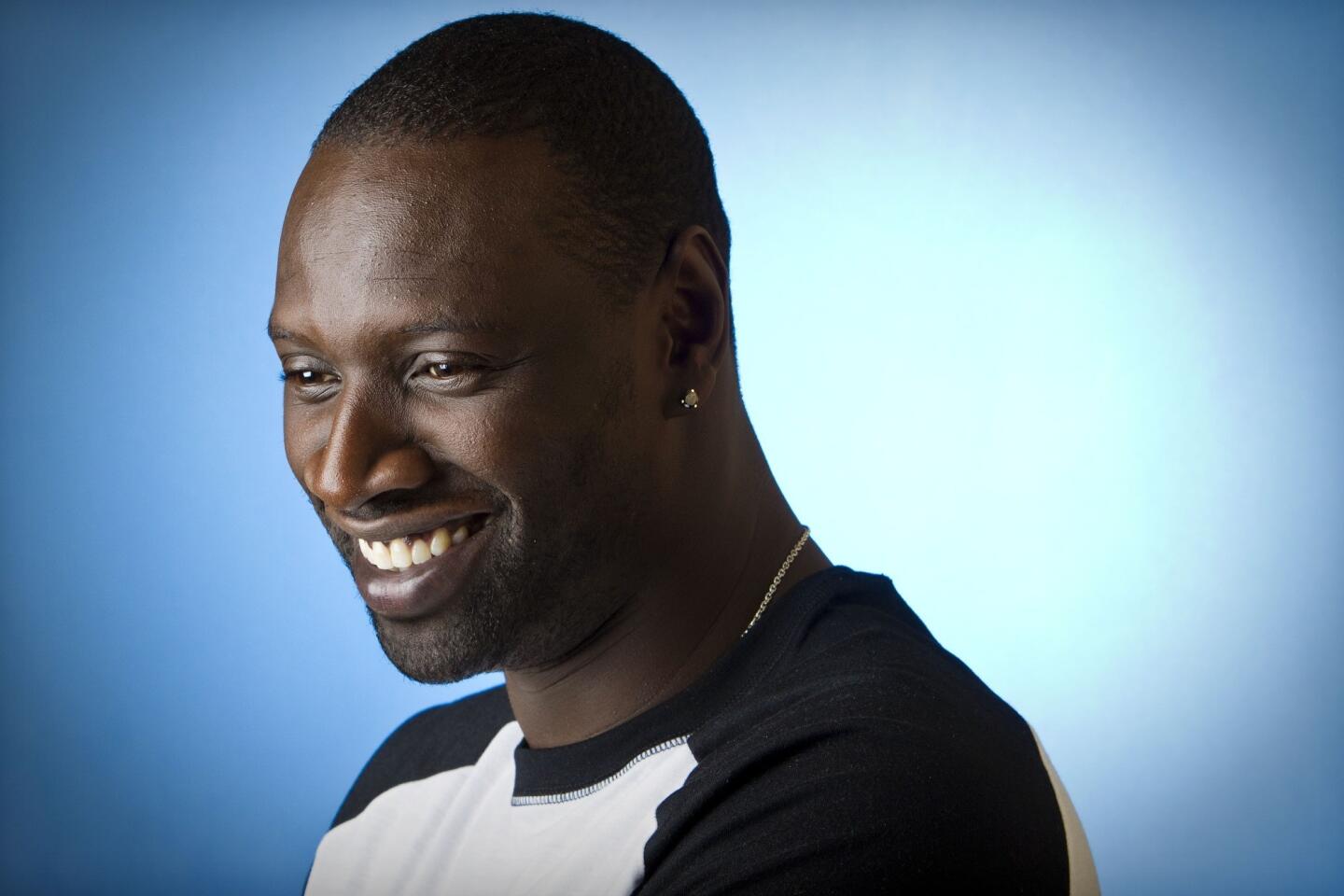

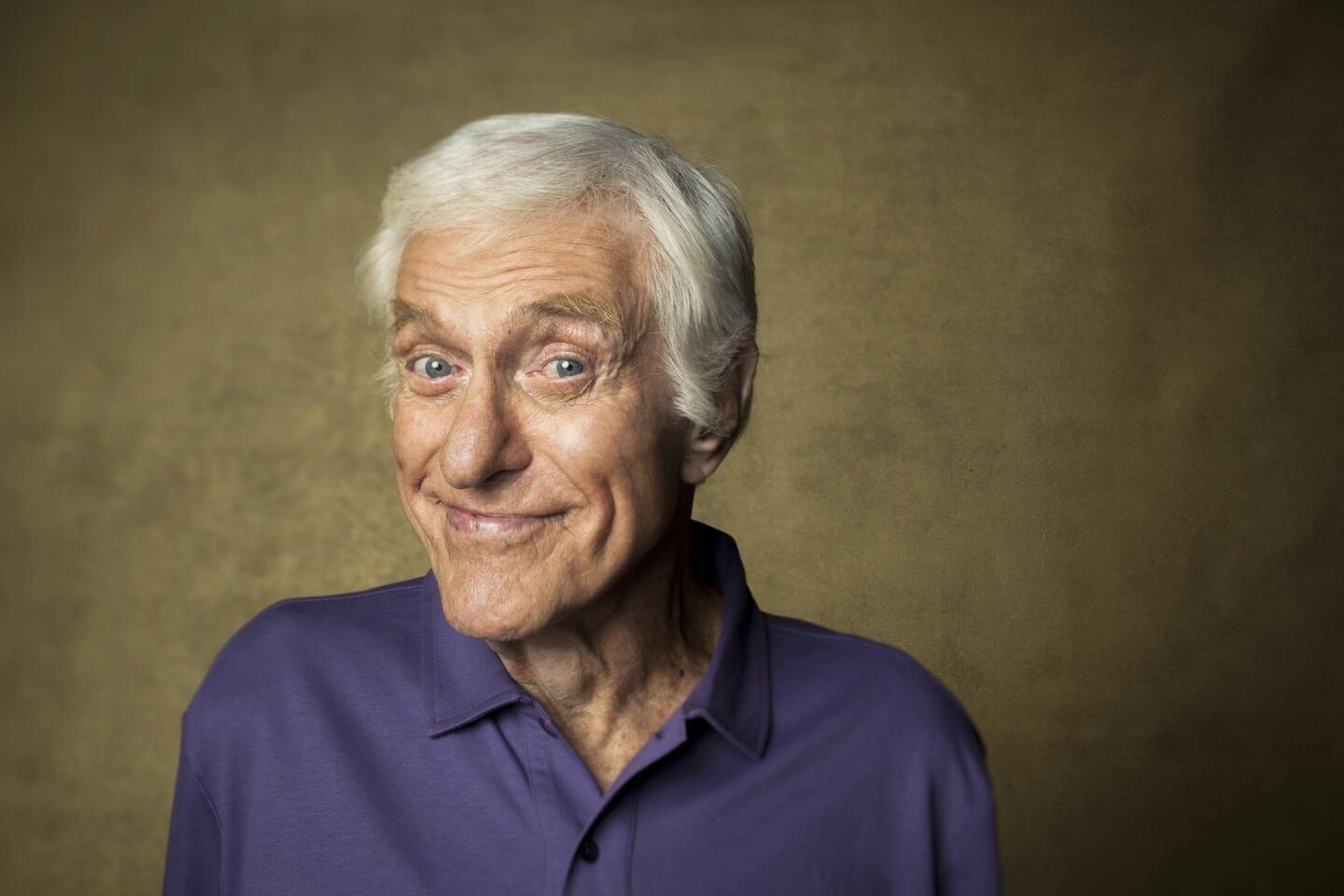

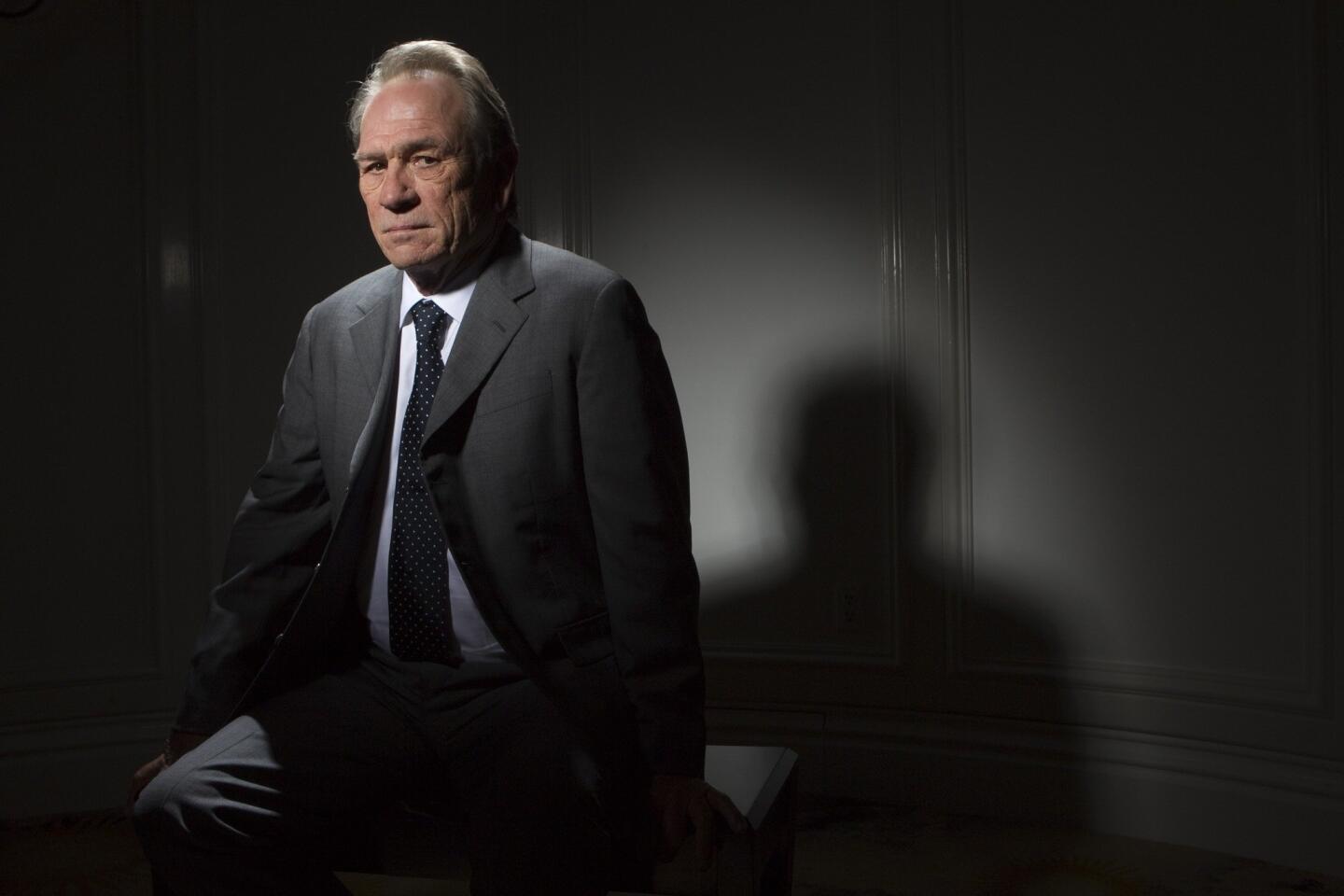

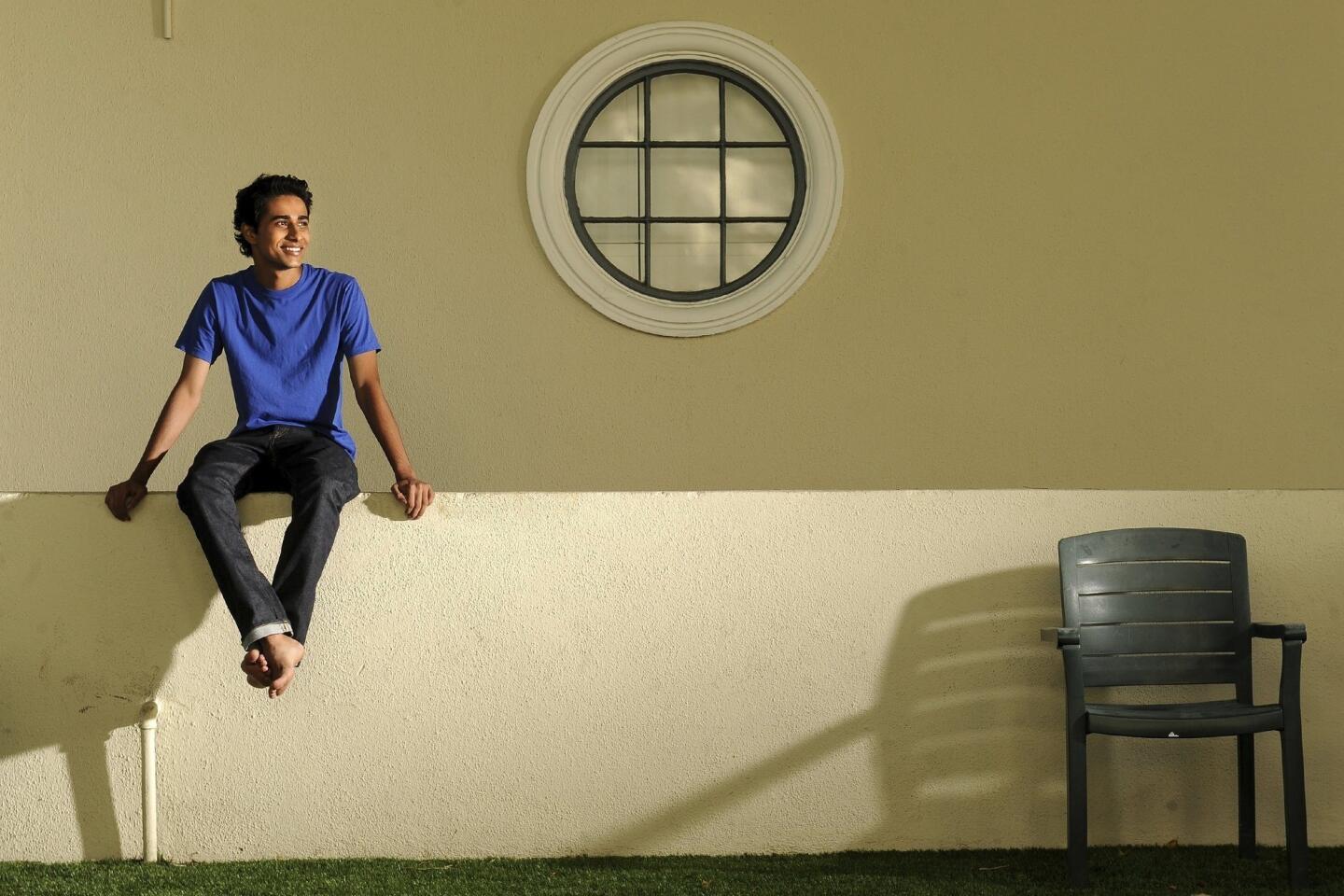

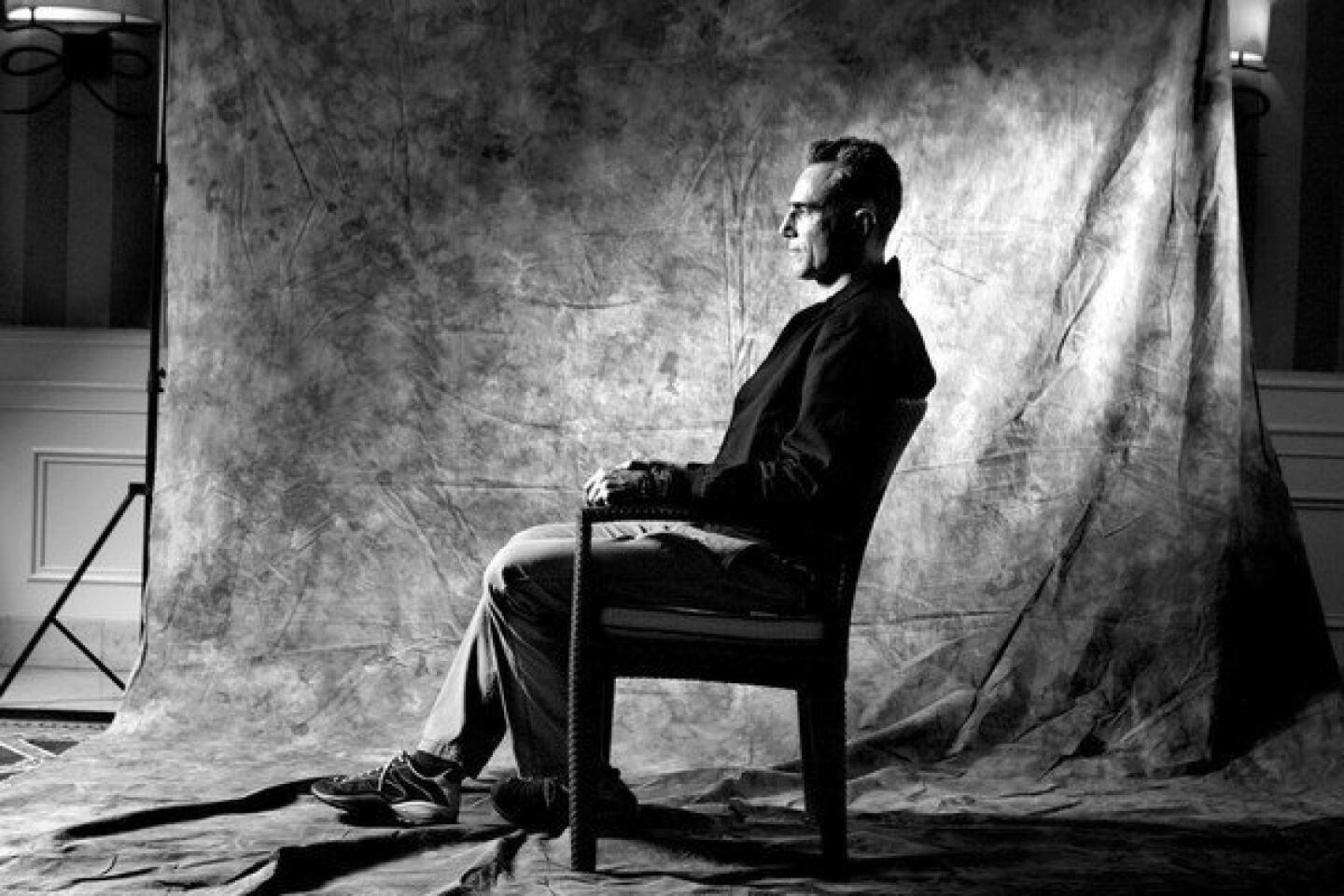

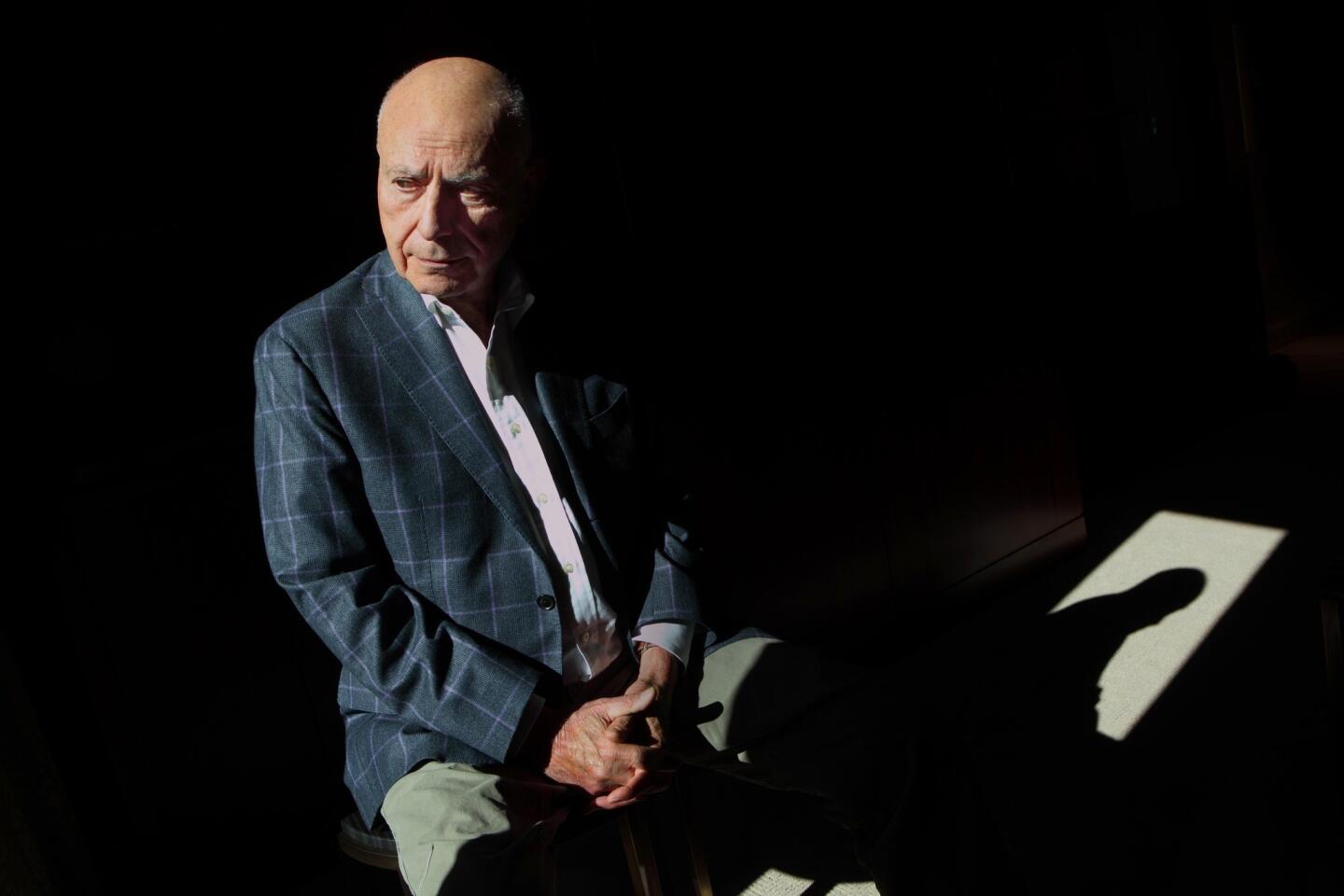

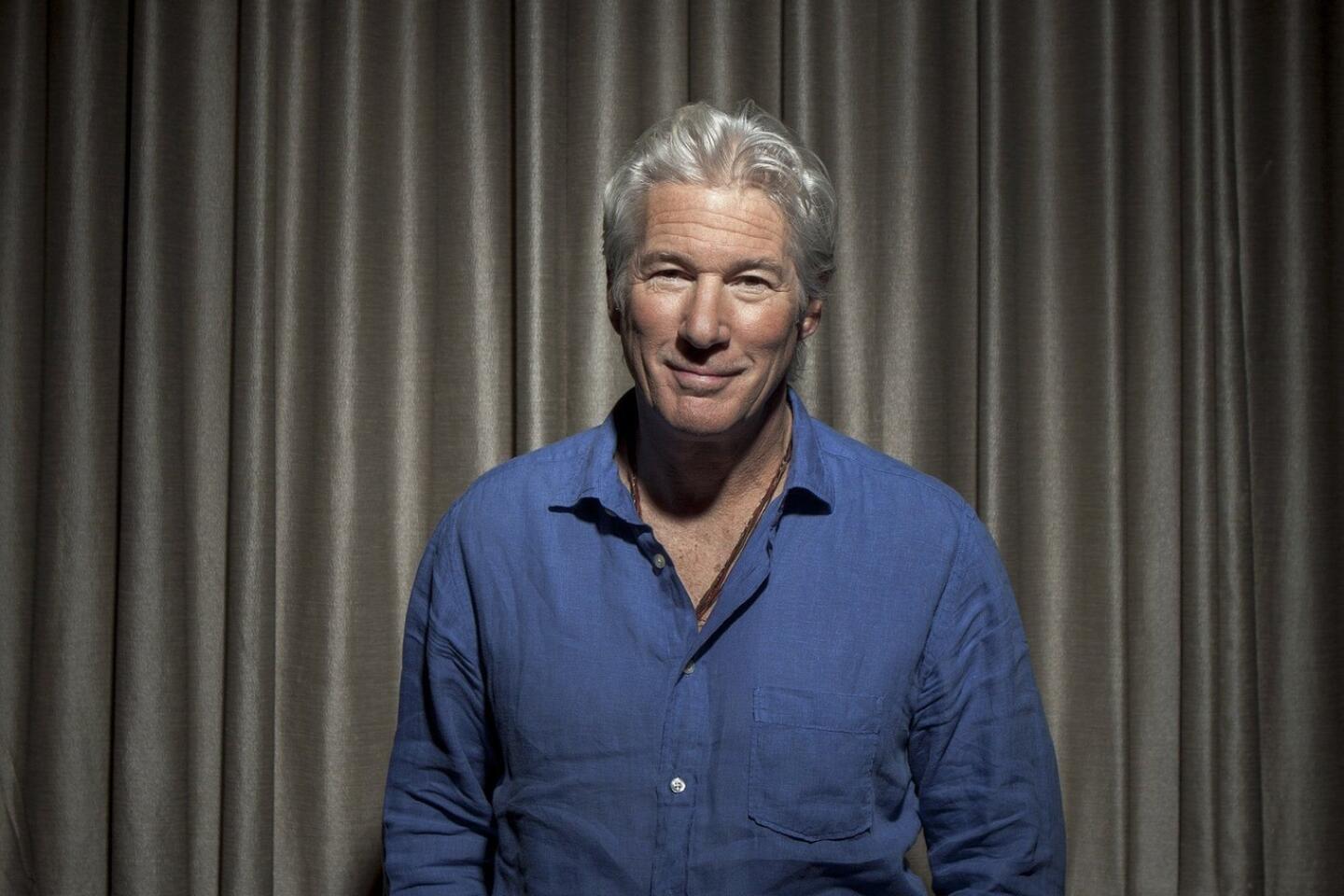

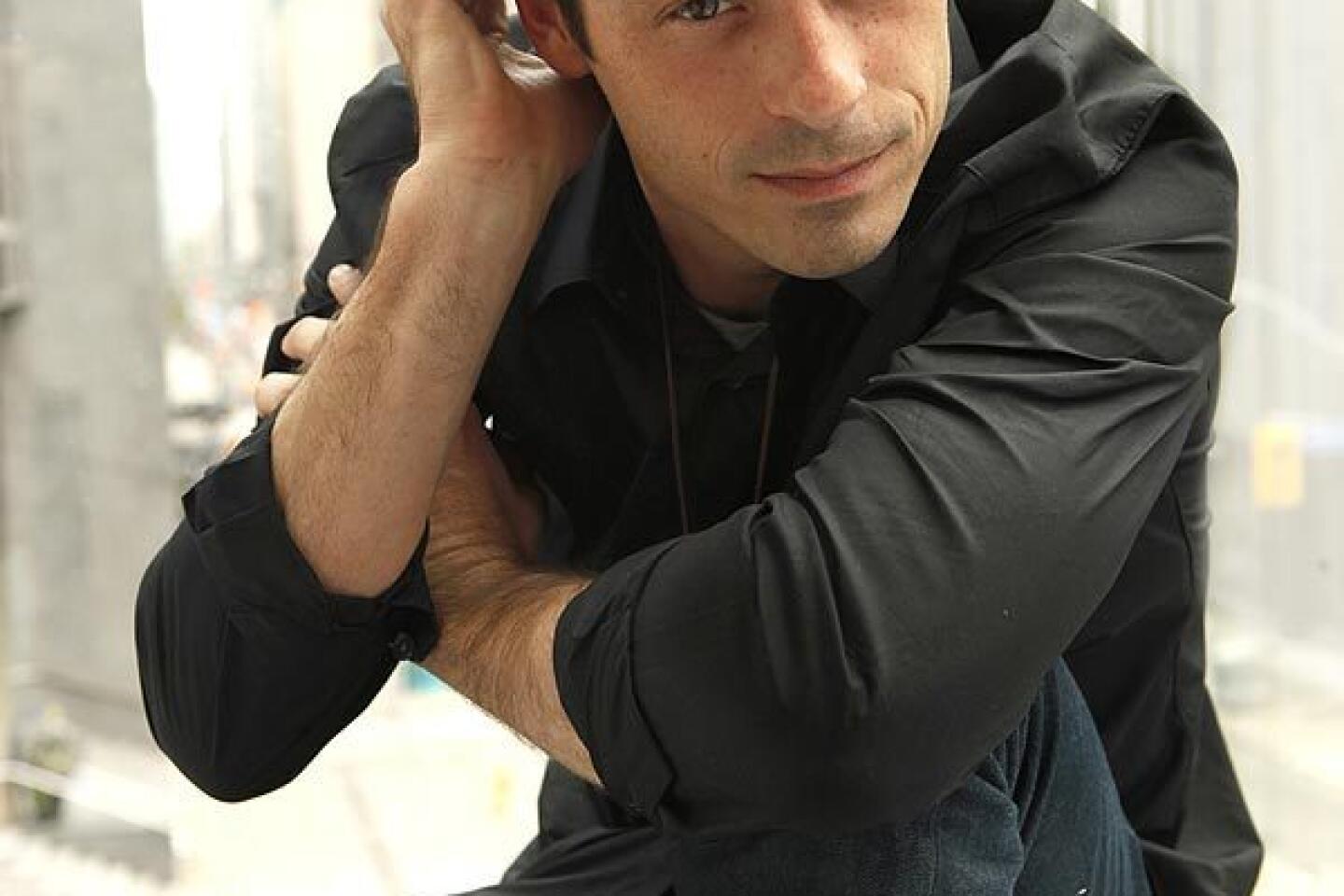

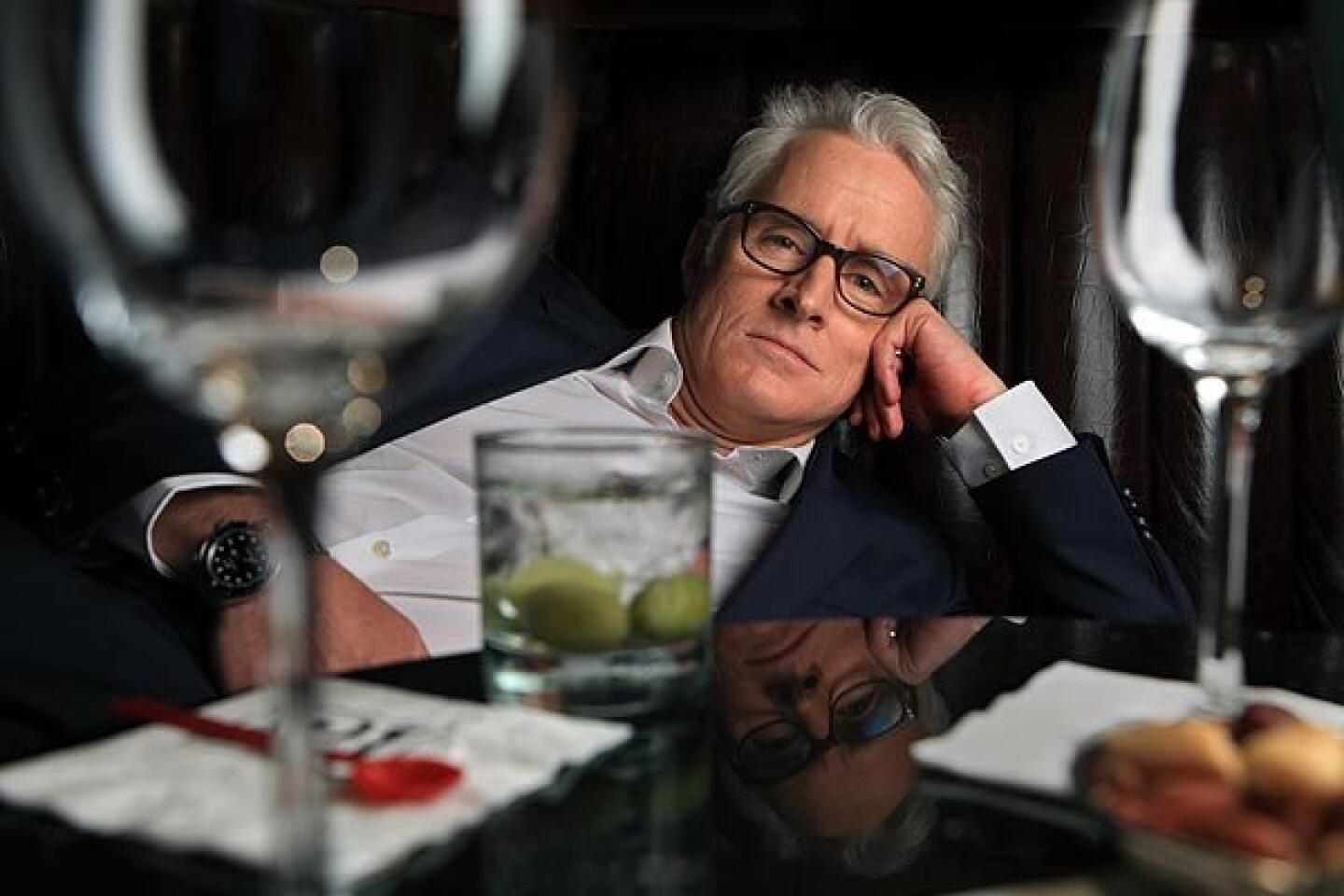

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by the Times

Schedule crammed to the breaking point, Blanchett discreetly insinuates herself into a backroom table at Gordon Ramsay in the London West Hollywood hotel for a late dinner interview after a long day’s work on a new Terrence Malick project.

It’s so late, in fact, that her assistant has already relayed to the wait staff Blanchett’s order and mine before we have even been seated. The kitchen will soon be closing, but racing against the clock is just one of the many things this Oscar-winning actress, mother of three boys and cultural ambassador does well.

Given the hour, the demands of a Malick film set and the lingering jet lag imposed by a short and nearly completed L.A. trip, she should be dead on her feet, but she’s actually quite revved for conversation. Being in the moment, the thespian’s great secret, seems to come naturally to her, but wouldn’t she rather just get into bed than chat about how she and Upton have transformed the STC into an international powerhouse?

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by the Times

“Don’t you find that work, if you love it, is actually really invigorating?” she says. “It’s the downtime that’s difficult, although I’m quite good at downtime.”

Good luck trying to imagine Blanchett in couch potato mode. Although she and Upton are looking forward to resuming their life as freelancers after they step down from their perch as co-artistic directors at the end of 2013, they’re fully immersed at the moment in raising STC’s international profile.

The couple have brought a global perspective to the company’s stage offerings, importing auteurs (Hungarian director Tamas Ascher is the visionary behind this “Uncle Vanya”) and touring the world with their stable of homegrown acting talent. For this Chekhovian enterprise, the cast (a “historic” one “in Australian terms,” says Blanchett) includes John Bell, Richard Roxburgh, Hugo Weaving and Jacki Weaver.

What possessed a star in the prime of her film career to take overAustralia’sprincipal theater, an opportunity that she says came out of left field?

“Andrew and I have a healthy lack of consequence,” Blanchett answers drolly. She insists there is no master plan. “I’m scared of actors with a scheme,” she says, later revealing that the roles she has done with the company weren’t ones she was necessarily angling to play but were made exciting to her by a director’s vision.

“It wasn’t as though I was leafing through Shakespeare at home and decided that I must do Richard II,” she says of her decision to play the effete king in “The War of the Roses” in 2009. Blanche DuBois, whom she sensationally portrayed under the direction of actress Liv Ullmann in the company’s 2009 production of”A Streetcar Named Desire,” troubled her as a character and daunted her as an acting challenge. Yelena in “Uncle Vanya,” she notes, “isn’t even onstage all that much.”

PHOTOS: Celebrity portraits by the Times

“The role,” she says, “is always the last point of attraction.” It’s the collaboration that’s the real enticement. She would have been content, she says, to have been a fly on the wall for the vintage “Vanya” cast that has been assembled.

“If you only exercise your soloist muscles,” she says, “the other muscles quickly atrophy.”

“Theater was always the center of our artistic identity,” says Upton, speaking by phone a few weeks later. “Coming from Sydney and having worked here originally, we knew many of the folks in the scene — knew the blood of it, if you like. A big attraction was to be a part of this groundswell of energy. I don’t think we would have run a company anywhere else.”

Upton, a director and playwright who has been focusing his writing efforts on translations and adaptations of classics while running STC, has supplied the version of “Vanya” that was prepared expressly for Ascher’s production. But just as his wife didn’t take on the administrative, fund-raising and lobbying burdens of being an artistic director to augment her acting opportunities, Upton has a larger mission in mind than his own advancement as a writer.

“We always felt that the work here in Sydney was of a very high quality and that it had an interesting perspective on the classics as an English language-based post-colonial colony,” Upton says. “We thought we’d have a chance to get this work out internationally with Cate’s connections and encouragement. And at the same time we’d have the nourishment of working with different traditions and approaches.”

Blanchett, who is perhaps more beautiful in person than she is on-screen even at 11 o’clock on a weeknight, reflects this cosmopolitanism. She self-deprecatingly says that she “wears the sparkly tops and has the blond hair,” while her husband deserves the credit for “the big ideas and big shifts.” In her glittering blouse, she does indeed light up this private room in Gordon Ramsay like an expensive Christmas ornament, but I can vouch that her mind is as radiant as her appearance.

She has the avidity of a true theater person. Before the tape recorder for our interview was turned on, she wanted to know what I had seen in the theater that had excited me lately. I talked about “Follies” at the Ahmanson Theatre and she wanted to know whether I had caught Ascher’s staging of “Ivanov” at the Lincoln Center Festival in 2009. (It was this production, which toured Sydney, that provoked Blanchett and Upton to invite him to do a Chekhov at STC.)

When she talked about touring Europe in Botho Strauss’ 1978 play “Gross und Klein” (Big and Small) this year, I had to stop her to ask whether she knew how rare it was that anyone of her Hollywood standing would have even heard of this German playwright.

She doesn’t seem comfortable being singled out like this and immediately brought up her friend “Phil Hoffman” — that’s Philip Seymour Hoffman to the rest of us — whom she bonded with in Rome while shooting “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” She appreciates that he is as serious about the stage as he is about film and says they “exchange notes” whenever they run into each other.

In making decisions about projects, what’s crucial to her, regardless of the medium, is the assurance that she’s in good directorial hands. Emotional exhibitionism isn’t the motive behind her acting. She wants to be a part of an artistic composition.

For a performer who shines the way she does, this ability to blend in stylistically, “to get the overview,” as Upton puts it, is quite rare and definitely one of her signature gifts, as no doubt Steven Soderbergh, Todd Haynes, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Martin Scorsese or any of the other highly distinctive big-screen auteurs who have worked with her would attest.

After about the second or third time I refer to her as a star, she repeats the word with a scoffing laugh. It doesn’t sit right with her, yet circling around her are assistants who are there to remind her which time zone she’s in and to keep her more or less punctual for her ever-fluxing schedule of appointments. There’s also a protective reserve of glamour about Blanchett that isn’t easy to pierce. Her conversation is engaging and warmly intellectual but not especially intimate. When asked whether she got into acting because she wanted to hide or reveal herself, she answers, “I just wanted to work.”

She’s not being evasive, but unlike American actors, she doesn’t feel the need to wear her woundedness on her sleeve. When I remarked how unlike Chekhov’s characters, who tend to live uncomfortably in the gap between their reality and their potential, she’s realizing possibilities beyond most people’s wildest dreams, she groaned and said, “I only see what I haven’t done.”

What inspired this articulate and seemingly level-headed woman from good suburban Melbourne stock to take up acting? She answers by way of a Roald Dahl story, “The Sound Machine,” which had coincidentally left a deep impression on me just a few months earlier. It’s about a man who invents a machine that allows him to tune into the agonized cries of trees, plants and flowers — to hear, in effect, the suffering the rest of humanity is deaf to.

“I think in a way that’s the part of your sensibility that gets turned on as an actor, and it gives you such a unique and privileged perspective on the world,” she says. “The challenge is to keep that open.”

Nothing seems to do that as effectively for her as acting before a live audience. Although she’s best known for her movie work, her theatrical resume has impressive credits that predate her stewardship of STC. She played opposite Geoffrey Rush in David Mamet’s “Oleanna” at STC in 1993 and was the lead in David Hare’s “Plenty” at London’s Almeida Theatre in 1999.

Now that she’s a mother as well as a theater producer and regular ensemble member, she has been strategic about her film schedule, taking off months when needed. No doubt her ongoing participation in the “Lord of the Rings” franchise, along with her Academy Award for playing Katharine Hepburn in “The Aviator,” have enabled her to become more selective.

“When you’re onstage, you’re acutely aware of the reaction of a particular group of people, because it’s like a wave,” she says. “No single audience is the same. And, you know, when a play is as well directed as a production of ‘Uncle Vanya’ or the Strauss play we just toured in and which Benedict Andrews directed, the architecture of the evening is sturdy and strong, and you can thrash against it and reinvent it every night.”

Reinventing Chekhov in the theater is a major reason for this “Vanya” undertaking. The production, which received rapturous reviews last summer at the John F. KennedyCenter for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., seeks to restore the comic dimension of a playwright who was frustrated himself with the ponderous way his work was staged by his great directorial collaborator Constantin Stanislavsky and whose work is still often presented in a languid, tear-stained manner today.

“What Tamas is able to find in Chekhov is the Chaplinesque quality, the melancholy of the clown,” says Upton. “There are indeed moments that you would call slapstick. Astrov, who’s played by Hugo Weaving, falls out of a window. Cate’s character falls through a door that opens behind her. But they’re not gratuitous moments. They occur at points when everything is getting a little mad and silly because of the growing passions between people that are unexpressed.”

Connecting the fertile European sensibility of a world-class director like Ascher with the resourceful Down Under pragmatism of this STC cast is just what Blanchett and Upton had in mind when they agreed to shoulder the responsibility of guiding a theater. Blanchett, a star despite her qualms, surely has had to sacrifice time and energy to take on this leadership role, but sitting thousands of miles from home in a restaurant that has all but emptied, she seems in no particular hurry to finish her second glass of wine or to stop sharing all that she has gained from the experience.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.