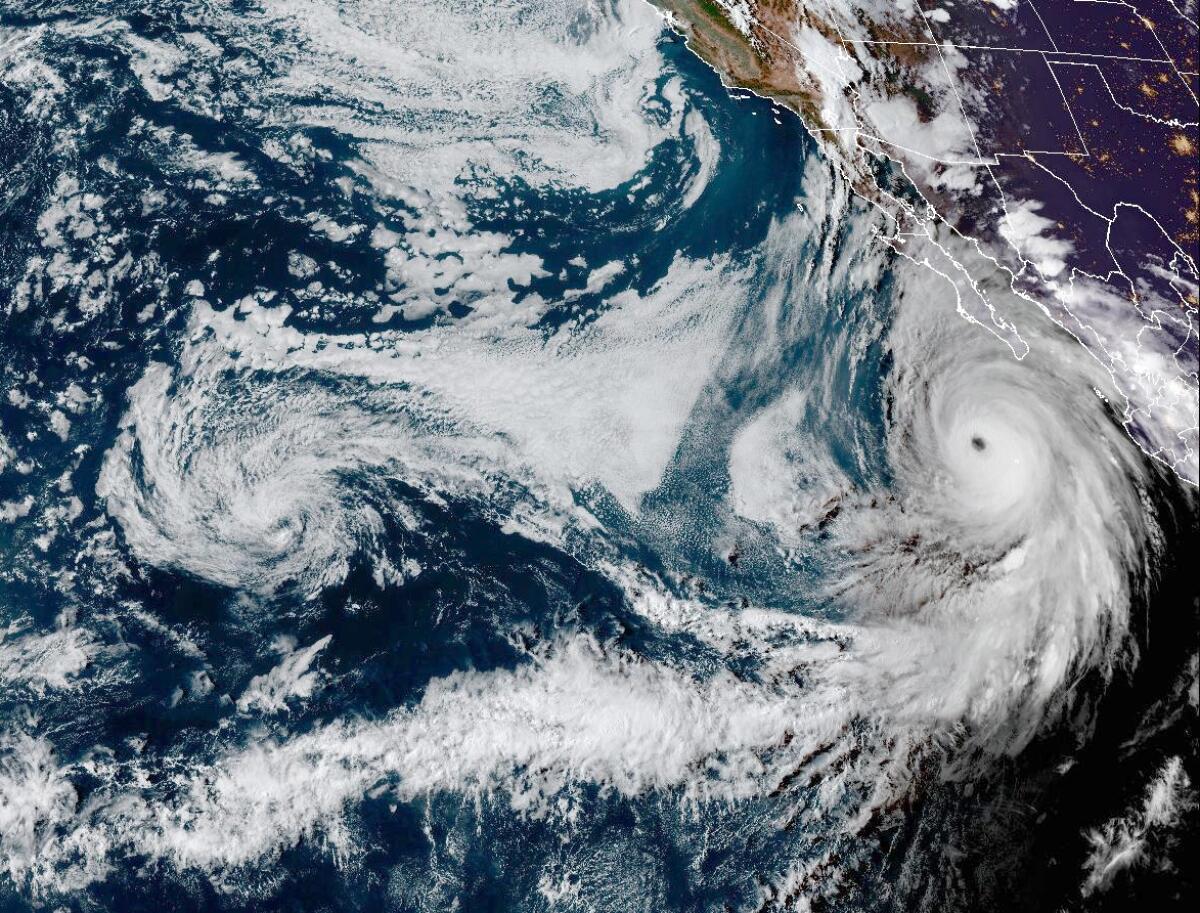

A marine heat wave off California helped fuel Hurricane Hilary. What’ll it do next?

- Share via

Last week, a massive marine heat wave sitting roughly 60 miles off California’s coast oozed eastward, providing warm water fuel for Hurricane Hilary and its historic trek north.

It was a worrisome development for researchers who have monitored this warm mass for nearly a decade — and who are watching a developing El Niño in the equatorial Pacific.

Ever since the “blob” appeared in the northeastern Pacific at the very end of 2013 — a massive marine heat wave that gripped the West Coast for nearly two years in heat and drought, disrupting marine ecosystems up and down the coast — a massive offshore heat wave has appeared nearly every year (with the exception of 2017 and 2018), expanding in the summer and shrinking in the winter.

For the most part, the northwesterly winds that blow along the United States’ Pacific Coast have worked to keep the heat wave offshore — keeping the near coastal waters cool as the deep, nutrient-rich waters of the eastern Pacific churn upward as the planet spins.

But now, when they die down or lose strength — which they occasionally do, especially in the late summer to fall — the marine heat wave moves in.

Plastics are everywhere. As an environment reporter, I make informed choices when shopping, trying to minimize the amount I bring in. Or I thought I was.

The heat waves “come right to the coast about this time of year and then as we go into the fall, they tend to slowly shrink and sort of recede and drift back to the west. But they never go fully away,” said Andrew Leising, a research oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “The next heat wave typically grows right in the same spot where the last one died off.”

He said they don’t entirely understand what is happening out there, but “we’re thinking there’s still some remnant warmth from the last one. And it just keeps building and building and building.”

“I think the thing that we’re always sort of watching is — with this warm water sitting offshore — is it going to come in and impact the coast,” said Michael Jacox, an ocean scientist with NOAA. “That was what distinguished the blob from the ones that have happened since — it reached the coast and stayed really warm for a really long time.”

It’s of particular concern this year as an El Nino system churns in the Pacific, pushing warm waters north and east.

The last time an El Niño came to town, it was 2014 — around the time the blob first appeared. And they both hung around until 2016.

The one-two punch of warmth and duration created a long-lasting algae bloom that killed marine mammals and disrupted the Dungeness crab fishery. It also disrupted the food chain and led to massive bird dieoffs.

“It’s a precarious situation because we’re on the brink of having a dramatic warming again,” said Nate Mantua, an NOAA fisheries and climate scientist.

The Hawaiian Islands do see wildfire from time to time, but the catastrophic Maui fires were spawned by a striking mix of factors, including climate change.

But Josh Willis, at NASA‘s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said that while these systems occupy the same ocean, it’s not clear the El Niño will do much to change the pattern of the heat waves in the North Pacific, or vice versa.

That’s because the El Niño is an ocean pattern, while the heat waves are atmospheric — defined by sea surface temperature anomalies detected by satellites.

What is clear, he said, is that climate change is warming the planet, leading to overall warmer temperatures that are likely to have an effect on both the El Niño and the heat waves.

And even though the current El Niño is considered “moderate” in intensity, it has spawned a historic hurricane season in the Pacific. Hurricane Dora kicked up winds that fueled devastating wildfires on Maui, in Hawaii, while Hurricane Hilary made its way up the Baja California peninsula before hammering Southern California as a tropical storm.

Climate change is “going to take us on a wild ride,” said Willis. “The extremes are getting more extreme. What used to be uncommon is now happening all the time. So, we have to get ready for that, you know, we have to prepare for the unexpected.”