Requiem for a bookstore: Caravan writes its final chapter

- Share via

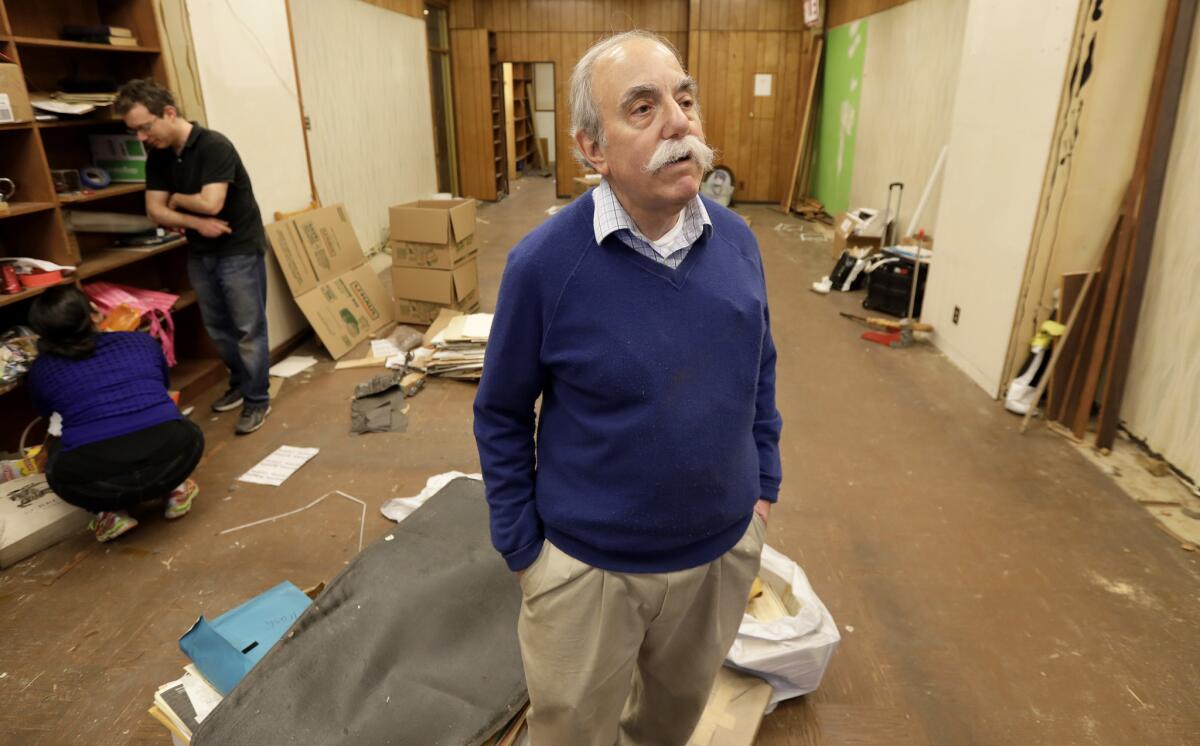

Moving day arrived Tuesday morning at Caravan Book Store in downtown Los Angeles, bringing with it an air of weary resignation.

Four weeks of 12-hour days had led to this ruin: shelves pried from the walls, their inventory labeled and packed, the small stage for the window display a heap of plywood, veneer and two-by-fours.

“I’m OK with this,” said the owner as he shuffled among the stacked boxes destined for the vans at the curb.

What had been a jewel box of antiquarian surprises — an artful display of old books and lithographs, ship models and toy trains, memorabilia and Americana — was now a way station for cardboard, packing tape and bubble wrap. If it had not been for his children helping, it might not have happened.

“This is fine,” said Leonard Bernstein. “This is normal.”

A month ago, he had announced that Caravan would be closing and there would be no equivocating. He was leaving his cozy warren on Grand Avenue for the efficiencies of email, telephone, mail and appointment. It was time, he said.

At first, his customers couldn’t believe it. Sandwiched between Starbucks and the Biltmore, Caravan had long played the village eccentric. It had the door chime, musty smell of leather and buckram and a charming proprietor with a Sam Elliott mustache.

At the news, they stopped by, grabbed a title at discount and wished him well. He tried to reassure them. This is not a sad occasion, he said; the business was doing well and would continue. He just wanted to take it easy, tend to his garden, be with his family.

Still, 64 years are hard to walk away from. Bernstein had grown up in this store, taken it over from his parents. Their memories were his memories, each fixture and curio a story unto itself.

The tall bookshelf? Built by his father in high school with the help of an uncle. The nautical clock? It came from the purser on the Andrea Doria. The glass display case? John’s Pipe Shop on Spring Street.

Bernstein tried to put on a good front, yet he admitted to a mix of emotion — not quite depression, melancholy perhaps — most acute at the end of the day.

“But once I get here, I’m fine,” he said in the early days of the packing up and pointed to his books. “These are my friends.”

The landscape of Southern California is littered with memories of lost bookstores: George Sand on Melrose, the Bookworm in Upland, Fahrenheit 451 in Laguna Beach, Papa Bach in West Los Angeles — shops that reflected a more idiosyncratic city.

Caravan was one of the last, its business never about the bestseller or most popular. Its collection, reflecting the strange and wonderful tastes of its owner, invited visitors to imagine the world as it once was. Sidewalk wayfarers never knew what they were missing until they wandered inside.

Amid these dusty aisles, browsing meant exploring, and ignorance was a door opening onto the unexpected: the Labrador coast in the 1920s, the Chicago barn belonging to the O’Leary family, the kitchens of the Lake Avenue Congregational Church in Pasadena whose members compiled a cookbook in 1970.

Easily overlooked and forgotten, these books and stories felt especially compelling when stumbled upon by accident. They rewarded those who valued the hunt and those who appreciated serendipity.

Caravan’s closing is more than the loss of another bookstore. It is the loss of a rare opportunity to get lost, to ignore the signposts of popular culture and discover something new. It helped that Bernstein was always nearby, happy to answer questions, scatter breadcrumbs along the way.

The store’s absence — for those inclined to ask — now raises an important philosophical question:

How will we learn about something if we never knew it existed?

Think about what you can do with your time, his daughters and his son would remind Bernstein, but he brushed them off. This was what he wanted to do with his time.

Then one day in January, he woke and knew what he had to do. He had read the obituary for Fred Bass, owner of the Strand Bookstore in New York City who had died in January, and last May, Bernstein’s next-door neighbor — Jeff King, of the Water Grill on Grand — had unexpectedly died.

Bernstein would turn 72 in June, and the lease on the shop was about to expire. So he began collecting empty boxes.

His parents had opened the store on May 15, 1954, when nearly a dozen bookstores competed for business around the corner on 6th Street, each catering to a specific clientele.

Morris and Lillian had planned to sell Bibles, but they soon diversified, focusing on “the old and new, curious and rare,” as the slogan had it.

When Times columnist Jack Smith visited Caravan one rainy January afternoon in 1971, he pronounced the store “an anachronism, stuffed with musty antiquities.” At the time, the other bookstores downtown had been replaced by “airline offices with exotic young women in chic uniforms.”

As a child, Bernstein pushed a broom around the store, washed the windows, and years later, when his father got sick and his mother had a stroke, he took their place.

Like a redwood tree growing new rings each year, Caravan grew, its inventory the slow accretion of books filling these 1,000 square feet, layer upon layer. Once-forgotten corners and hidden shelves were pushed into greater obscurity with each new acquisition.

“You’ll never know what I found the other day,” said Bernstein, who takes delight in his own discoveries. “My grandfather’s driver’s license, hidden in a box in a desk drawer.”

He had thought of becoming an anthropologist and worked briefly as a high school teacher, but like George Bailey, he ultimately contented himself in this Bedford Falls.

Only he didn’t have to dream of traveling: The world came to him.

There was former CIA director William Casey, researching the American Revolution. Robert Joffrey once dropped in looking for books on ballet. Phyllis Lambert escaped her job restoring the Biltmore in the quiet of his shelves, and Marcus Crahan, coroner for L.A. County, perused the collection for cookbooks.

Jimmy Carter, Caroline Kennedy, Sting, Dustin Hoffman, Jodie Foster and Matt Groening had visited, and then there was the bike messenger with the holes in his shoes and the dishwasher who used books to prop up his computer at home.

To have stood inside his store is to have been surrounded by the devotion of authors who steered away from their self-doubt and worry and focused years on subjects they found meaningful.

James Huneker, Octave Chanute, Prince Serge Wolkonsky and C.V. Waite may be forgotten, but their books represent both sacrifice and aspiration — realized or not — for profit, fame or historical regard. Their obscurity today only makes their efforts more poignant.

Caravan provided a canvas not only for authors but also for readers. These pages contain the penciled marginalia, inscriptions, clippings and even letters: reminders that books carry with them a more intimate history of love and then loss.

Bernstein owns the sonnets of 14th century Italian poet Petrarch, who wrote more than 300 poems to Laura. In the endpapers was the inscription from Tom to Bonnie, reading “to my Laura.”

“This is the downside in this business,” Bernstein said, “to see an emotion in a book at some other time. So where’s Bonnie? How did she let it go, so that I have it? Sometimes books lead me to the end of someone’s life when they don’t want that memory.”

He looked at a yellow poster board with green block letters and a slight shadowing of red. Tiny adhesive stars decorated the words, “Books are lasting gifts.” His mother made that sign, and he’s still touched by the message, so simple and naive.

Bernstein offered to sell Caravan to his children. Give me a quarter, he told them, and it’s yours. But they turned him down. “We can’t do what you do. You’ve got the mustache,” they said.

“Maybe I’m a fool for holding onto the past,” he said, “but that’s what’s guided me. What would Mom do? What would Dad do? Now I defer to a younger generation.”

On Tuesday, the pedestrians on Grand Avenue were oblivious. Cellphones stuck to their ears, coffee in their hands, they breezed by.

With balletic precision, movers swept yard carts under stacked boxes and angled their loads out the door, and by late afternoon, Caravan was an empty shell. The rain had started to fall. Years ago, Bernstein had written this script.

He was 24, and Los Angeles was a gleam in his eye when he wrote a little book that he called “Children of the Queen of the Angels” and filled with portraits of the city’s more colorful residents: the Screamer, the Bird Man, the Scratch Man, the Entrepreneur and Propeller Man.

“Someday these ‘children’ will disappear,” he wrote. “The Queen of Angels is already losing some of her brilliant offspring. New characters appear, but without the same luster.”

Fifty years later, his words have returned to him. It is the Book Man who has now disappeared.

For the Record, March 8, 8:21 p.m.: A previous version of this story said that Papa Bach bookstore was in Santa Monica. It was in West Los Angeles.

Twitter: @tcurwen

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.