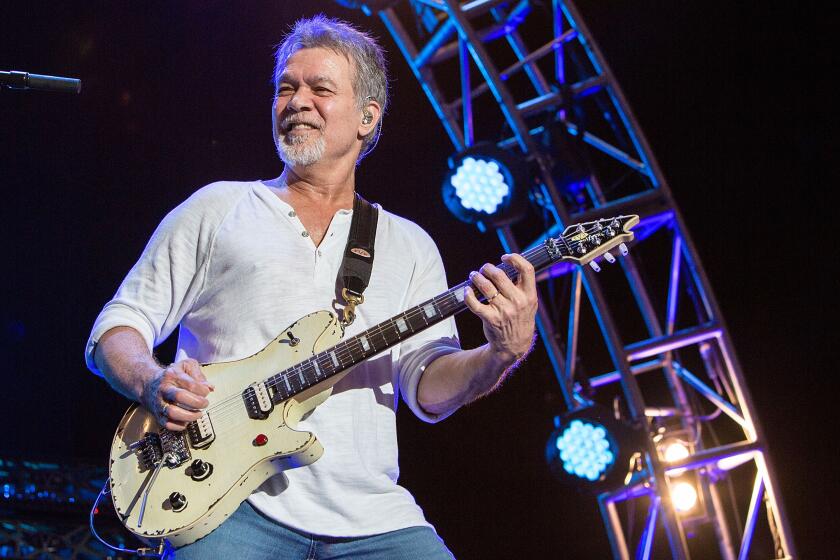

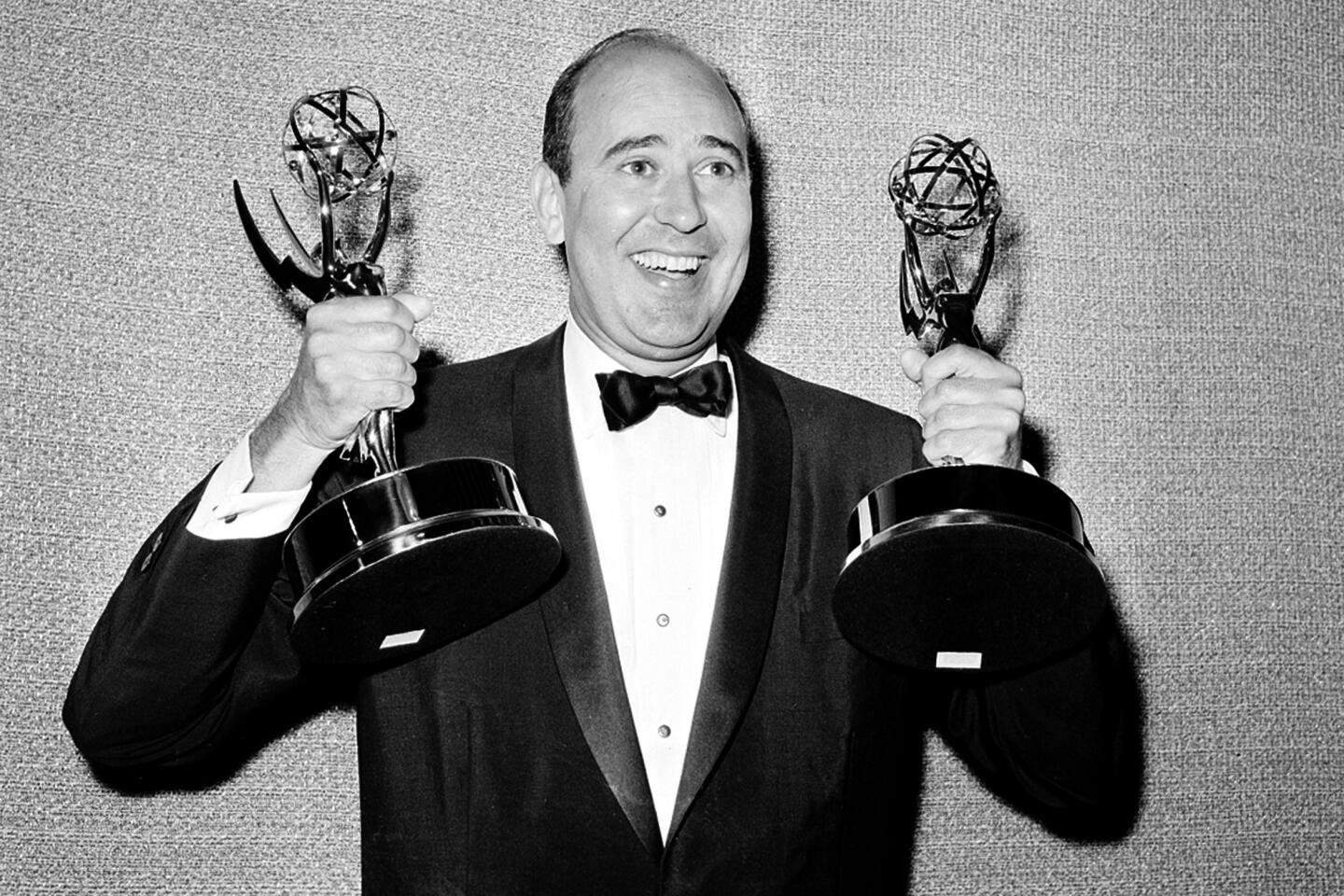

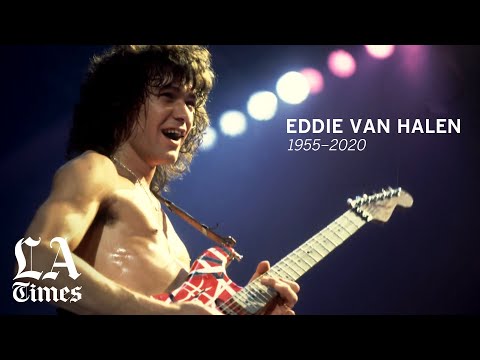

Eddie Van Halen, grinning guitar god for a rock generation, dies at 65

Eddie Van Halen, legendary lead guitarist for the wildly popular hard-rock band Van Halen, has died of cancer at 65.

- Share via

With a road-battered guitar, lightning-quick fingers and a welcoming good-time grin, Eddie Van Halen and his band Van Halen may have been just what the 1970s needed.

Amid a sea of aging ’60s rock acts and forgettable radio fare, Van Halen brought a refreshing jolt of energy to the stage with his hard-rock hooks and wild guitar flash in the Jimi Hendrix tradition. By the time the decade had come to a close, he’d become as influential as any guitarist who came before.

“Ed’s a once- or twice-in-a-century kind of guy. There’s Hendrix, and there’s Eddie Van Halen,” friend and guitarist Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains said earlier this year. “Those two guys tilted the world on its axis.”

In poor health for years, Van Halen died Tuesday at age 65. The cause was throat cancer.

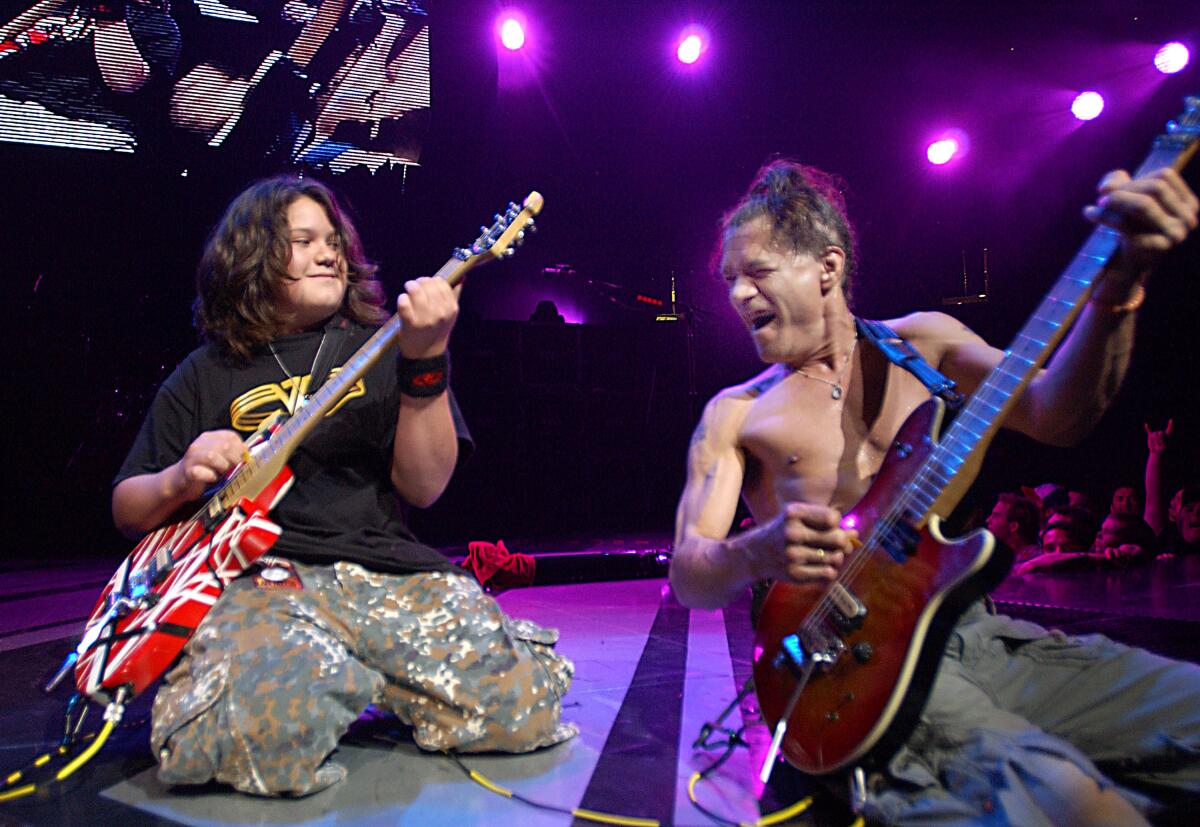

The musician’s death was confirmed by his son, Wolfgang Van Halen, on Twitter. He did not say where his father died.

“He was the best father I could ever ask for,” he tweeted. “Every moment I’ve shared with him on and off stage was a gift.”

Guitar virtuoso Eddie Van Halen died Tuesday at 65. Here are 20 career-defining performances.

Eddie Van Halen, who had emigrated from the Netherlands as a child, emerged from Pasadena with what seemed a natural understanding of what the rock world needed. His speed and innovations along the fretboard inspired a generation of imitators, as the band bearing his name rose to MTV stardom and multiplatinum sales over 10 consecutive albums.

In contrast to the shadowy gothic blues of Black Sabbath or the pagan thunder of Led Zeppelin, the band Van Halen delivered muscular hard rock in Technicolor. The group’s sound and image were vivid reflections of its Southern California home, with a lead guitarist in bright colors.

His iconic guitar, named Frankenstein, was pieced together to his personal specifications in 1975 from the components of other instruments: a $50 body, a $75 neck, a single Humbucker pickup and crucial tremolo bar. With a red surface crisscrossed frantically with black-and-white stripes (and traffic reflectors stuck to the back), it remains one of the most recognizable guitars in rock ’n’ roll.

The idea was to stretch out and get loud, he once said, as he referenced the fictional metal act Spinal Tap, whose members bragged on camera that their amplifiers went all the way to 11. “While they’re going to 11,” Van Halen joked during a 2015 appearance at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., “I was already going to 15.”

As a band, Van Halen made other contributions to the era’s resplendent rock-star lore: demanding that no brown M&M’s appear anywhere backstage; drummer Alex Van Halen crescendoing at concerts with a flaming gong; singer David Lee Roth high-kicking in leather chaps with a bare backside.

If older brother Alex was his closest musical partner throughout Eddie Van Halen’s life, in Roth he found a key collaborator and sometime nemesis, who brought a showbiz flourish to the guitarist’s virtuosic, mad-scientist metal. Until Roth’s exit at the peak of the original band’s popularity in 1985, the duo epitomized the eternal struggle between guitar hero and lead singer, each fueled on hyperkinetic energy, if not always in sync.

“Dance the Night Away” video by Van Halen

After Roth was replaced by singer-guitarist Sammy Hagar, the platinum-selling singles and albums kept coming for another decade. The streak made Van Halen one of the most successful bands in rock history, including two albums with Roth that reached diamond status (10 million copies sold): 1978’s debut “Van Halen” and 1984’s “1984.”

At 25, Van Halen married popular TV actress Valerie Bertinelli, 21, in a 1981 wedding swarmed by paparazzi. A decade later, they had a son, Wolfgang, who grew up to join the family business as bass player in the band. The couple separated in 2001 (and divorced in 2007), in part because of the guitarist’s worsening drug and alcohol abuse, which eventually helped destabilize the band.

Van Halen, wrote reviewer Richard Cromelin, stands “a good chance of moving from the L.A. circuit into national popularity.”

Edward Lodewijk Van Halen was born Jan. 26, 1955, in Amsterdam to a Dutch father and an Indonesian mother. His father, Jan, was a classically trained clarinet and saxophone player who traveled the world playing music and passed his obsession to his sons, Eddie and Alex.

Their parents hoped the boys would become classical musicians, and the two were given piano lessons as children. Eddie was 7 when the family left the Netherlands in 1962 for the United States, and his father performed with the ship band during the nine-day trip. Alex and Eddie played piano at intermission for tips.

Settling in Pasadena, the foursome shared a single room in a house with two other families. Van Halen’s mother, Eugenia, initially worked as a maid, while his father washed dishes and worked as a janitor, playing live gigs on weekends. Later, Jan’s rekindled music career in the U.S. kept him on the road for weeks at a time.

As elementary school kids with uncertain English, the Van Halen brothers performed during assemblies and lunch in a band they called the Broken Combs. Eddie bought a drum kit with money from a newspaper route but soon switched to guitar, beginning with a low-budget beginners’ model: a Sears Teisco Del Rey six-string.

An early rock inspiration was the Dave Clark Five, British Invasion hit makers from the mid-1960s, and Van Halen learned as a teen to play along to favorite records by slowing down the turntable. In later years, he claimed to rarely listen to contemporary music other than his own but acknowledged the lasting influence of U.K. guitar hero Eric Clapton, in particular his years in the super-heavy blues-rock trio Cream.

“I realize I don’t sound like him,” Van Halen told Guitar Player magazine in 1978, “but I know every solo he’s ever played, note for note.”

The Van Halen brothers attended Pasadena City College and formed a band called Mammoth, in which Eddie both played guitar and (briefly) sang. “I couldn’t stand it,” he told an interviewer later. “I’d rather just play.”

From rival bands, they recruited bassist Michael Anthony and Roth, the latter in part because the singer owned a PA system. The musicians agreed to name their group Van Halen, and they played backyard parties and high schools, graduating to the Sunset Strip clubs Gazzarri’s and the Whisky a Go Go.

Sammy Hagar, Gene Simmons, Lenny Kravitz and Kenny Chesney are among the musicians paying tribute to Eddie Van Halen, who died Tuesday at age 65.

A typical 1975 live set in Pasadena might have included covers of songs by the Rolling Stones, Robin Trower, Bad Company and David Bowie, each stretched out in strange new ways on Van Halen’s hot-rod guitar. Even more exciting were the band’s original tunes, which were explosive but melodic.

One night in 1976 at the Starwood nightclub in West Hollywood, Kiss singer-bassist Gene Simmons happened to catch the unknown band, with its grinning guitar phenom at stage left.

“This band comes on, and all of a sudden, I forget about everybody around me. I go, ‘What’s that?’” Simmons recalls. “Even though the band was a three-piece, there was a big sound coming out of them, and Eddie was tapping the neck — which I’d never seen done on guitar before — with speed and accuracy in the melody. They simply didn’t sound like anybody else. There was a kind of fury.”

Simmons signed them to a contract and produced a 15-song demo recording at Electric Lady Studios in New York. Kiss management didn’t get behind Simmons’ discovery, so the bassist let them out of their contract.

Van Halen was signed to Warner Bros. Records after label President Mo Ostin and producer Ted Templeman watched a performance at the Starwood on a rainy Monday night. Templeman told Rolling Stone years later: “There were like 11 people in the audience, and they were playing like they were at the Forum.”

The guitarist was 22 when his band recorded its debut album, “Van Halen,” released Feb. 10, 1978. It soon hit the top 20.

The band’s first single was “You Really Got Me,” a snarling cover of the Kinks’ early proto-metal hit. The guitarist latched onto the original riff and sent his fingers dancing over the fretboard. Other tracks on the debut now read like a Van Halen greatest-hits package: “Runnin’ With the Devil,” “Eruption,” “Ain’t Talkin’ ’Bout Love,” “Jamie’s Cryin.’”

“The way the first record starts, Eddie’s guitar sounds like a siren coming in at the end of the world, and then that pulse of ‘boom, boom,’ and they’re running with the devil,” Tool guitarist Adam Jones said after finally meeting his guitar hero backstage after a Tool concert in October in Los Angeles. “If anyone is playing from his heart, it’s that guy.”

Van Halen was on the road in Aberdeen, Scotland, when the players heard that their first album had gone gold in the U.S. They partied in celebration and trashed their hotel room.

On subsequent albums, the guitarist continued to evolve. During the making of 1981’s “Fair Warning,” he secretly returned to the studio in the early morning hours to refine his solos alone with a recording engineer.

In his memoir, “A Platinum Producer’s Life in Music,” Templeman writes: “He had profound things to say on the instrument. Guys tried to copy him, and none of them came close. He was like Charlie Parker or Errol Garner ... generational talents.”

The Van Halen brothers recruited their father to play clarinet on “Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now)” from the 1982 album “Diver Down,” the only time the jazz player and his sons recorded together. “The beauty of it was that we were all just equals in the studio playing,” Eddie told Rolling Stone’s David Wild in 1995, adding that his father, who died in 1986, “would get tears in his eyes every time he saw us play. He loved it. He lived through us, because he never really made it.”

“When I used the stuff I invented, I was telling a story, while I felt that the people who were imitating me were telling a joke,” he told Smashing Pumpkins leader Billy Corgan in a 1996 interview for Guitar World.

In 1982, producer Quincy Jones asked the guitarist to solo on Michael Jackson’s rock-leaning pop smash “Beat It.” Van Halen’s own crossover into the broader pop landscape was just ahead.

With cover art featuring a baby cupid having a smoke, the Van Halen album “1984” surprised fans with its first single, as the grinning guitar hero leaned into a keyboard riff for “Jump,” which became the band’s only No. 1 pop hit.

At 34 minutes, the album was the first recorded at Van Halen’s studio, 5150, built on his 7-acre home property in the hills of Studio City.

Amid the rock riffs and dive-bombing guitar asides on “Panama,” Van Halen forged a layered instrumental breakdown that mingled metal aggression with jazzy restraint, plus the sound of his 1972 Lamborghini revving.

After Roth’s exit in 1985, the guitarist considered recording a solo album, but he decided there was no need.

“All Van Halen records are solo records to me, because I have the creative freedom to do whatever I want,” he told Rolling Stone in 1995. “I don’t know what else I’d do.”

With journeyman rocker Hagar (formerly of the band Montrose and an established solo artist), Van Halen in 1986 released “5150,” their first album to hit No. 1 on the Billboard 200. There were significant shifts in the band’s sound — with more ballads and no instrumentals — but it was a rare case of a major rock band changing lead vocalists and maintaining its popularity.

Nicknamed “Van Hagar” by both fans and detractors, the Hagar-fronted band continued as a dependable hit maker into the grunge era. For the anthem “Right Now” (from the 1991 album “For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge”), the band even dabbled in sociopolitical commentary. In 1995, the ballad-heavy “Balance” was the band’s fourth consecutive No. 1 album in the U.S. with Hagar, but tension with the Van Halens led to his exit the following year.

“Eddie and I hit when I walked in that room — he played me a riff, and I started singing, and wow, man,” Hagar said in January of their creative partnership. “We did that for seven or eight years, and then the head-butt came.”

After a decade of trading insults in the media, Van Halen’s relationship with Roth took an unexpected turn when the singer was asked to sing two new songs for a 1996 hits collection, “Best of — Volume I.” The reunited quartet made its first joint appearance at the MTV Video Music Awards and had another meltdown backstage. Roth was out again.

“There was never any talk of anything permanent,” the guitarist insisted to The Times that year.

Fan confusion over a third version of the band in 1998, with singer Gary Cherone, contributed to what became its worst-selling album to that point, “Van Halen III.” But it did include Eddie Van Halen’s first-ever lead vocal, the solemn six-minute piano ballad “How Many Say I.”

With its third lead singer, former Extreme frontman Gary Cherone, the band launches a new album and world tour.

Hagar returned for an 80-date North American tour in 2004 that ended amid more acrimony.

“The reunion we had was a horrible thing, and it was a bad way to end,” Hagar said. “That’s why I wish him so well, because he was unhealthy then. We fought. That was a great band, but I don’t know what happened.”

The son of an alcoholic father, Van Halen began drinking and smoking at age 12 and struggled for decades with alcohol and cocaine. Several attempts at sobriety included a stop at the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, and by 2008, he declared himself sober for good.

Roth returned that year for a full tour for the first time since 1985. By now, the guitarist’s son Wolfgang was playing bass in the band. They released a new album in 2012, “A Different Kind of Truth,” built largely from song ideas resurrected from unused demos dating to the 1970s. It hit No. 2 on the Billboard 200.

When David Lee Roth talks, it’s ‘A Different Kind of Truth’

The band performed its final shows over two nights in 2015 at the Hollywood Bowl. That same year, Van Halen donated a replica of his Frankenstein guitar to the Smithsonian, while the original appeared behind glass at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Aside from drug and alcohol issues, Van Halen faced a variety of health crises. He underwent a hip replacement in 1999 and lost a third of his tongue to cancer. Though he was declared free of the disease in 2002, recent reports suggested that the cancer had returned. In a January interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, Roth said of the guitarist, “Ed’s not doing well.”

Van Halen’s name came up in surprising ways in 2019. He attended a Tool concert in Los Angeles, and a young fan in the audience randomly asked Van Halen to take his snapshot near the stage, not recognizing the platinum-selling guitarist. Wolfgang captured the moment for Instagram and called it “my favorite moment from the @Tool show last night.”

Weeks later, 17-year-old pop sensation Billie Eilish was teased by late-night TV host Jimmy Kimmel for not knowing of the band Van Halen. Wolfgang calmed outraged VH fans: “Listen to what you want, and don’t shame others for not knowing what you like.”

In October, Michael Jackson’s daughter Paris, 21, tweeted affectionately: “Get yourself a partner that’ll slowdance to Van Halen with you.”

The guitar master at the center of the band had no comment at the time. Van Halen was never fully comfortable with fame, often preferring the hours alone experimenting with his guitar to the big moments onstage.

Music was a family tradition, regardless of who was listening.

“Listen, my dad played until he died. I think it’s something you’re born with,” he said in a ’90s interview. “You’re either rock ’n’ roll or you’re not.”

Van Halen is survived by his second wife, Janie Van Halen, whom he married in 2009; son Wolfgang; and brother Alex.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.