Editorial: Five things ‘Defund the police’ is not

- Share via

The nationwide calls to “defund the police” in the wake of the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25 embody both the anger at continuing gratuitous police violence and a strategy for dealing with it. But do defunders want to constrain police, replace them, reimagine them or simply abolish them? Not everyone who chants or hashtags the slogan agrees on the details. For now, though, here are some things that “defund the police” is not:It’s not new.

One of the leading strategies to encourage better police behavior over the last 40 years has been ever-greater investments in technology to surgically pinpoint public safety problems, and in larger police forces to enable more humane community-oriented rather than occupation-style policing. But there has been a strong counter-narrative from communities in which more surveillance and more cops has meant more oppression rather than safer streets.

In the midst of the crack epidemic that began in the 1980s, the most succinct articulation of the dissatisfaction with the state of policing in Black neighborhoods south of downtown Los Angeles came not from street marchers or reformers but from the 1988 N.W.A. album “Straight Outta Compton.” “Defund tha police!” the group rapped in its most controversial track, except that they didn’t say “defund,” but a word that starts with an “f.” The work is a bill of complaints against not just policing but the inequitable economic and social structure of which it is a part. With minor editing it could have been the executive summary of a blue-ribbon commission report explaining how mistaken it was to spend money on greater police presence rather than on better health, education and employment opportunities. That was 32 years ago.

It’s not a panacea.

The Marshall Project has reported at length on the continuing problems in Chicago and Memphis, which cut their police budgets but did not reduce excessive force or improve the community’s regard for officers. Smaller forces meant larger backlogs of unsolved crimes and longer wait times for police response.

That experience is at the core of the fear voiced by critics of “defund the police”: What do you do when you really need a cop? Defunders answer that many times you need the kind of help best provided by a mental health professional, not an armed law enforcement officer who may be as likely to exacerbate the situation as resolve it. But still — sometimes you need a cop.

It’s not what happened in Camden, N.J.

The city across the river from Philadelphia had a police department beset by deep corruption, so it was disbanded and replaced by a new law enforcement agency. The move could best be seen as a “reset” rather than a full-scale defunding.

Nor is “defund the police” N.W.A.’s Compton, which disbanded its department in 2000 but replaced it with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, an agency with plenty of its own problems. Other cities, too, have had police do-overs, including Stockton, Calif., where municipal bankruptcy meant layoffs and early retirements that did some good by purging the department of many of its old-school warrior cops and paved the way for more constructive thinking and practices. Stockton, though, remains one of California’s most violent cities.

It’s not “reform.”

The “defund the police” movement critiques traditional police reforms such as body cams, oversight commissions, better training and more restrictive use-of-force policies. Defunders note that these things have been tried, but police killings, especially of Black people, continue.

Backers of reforms called #8cantwait recently apologized for putting forward a reform package, because they said it distracted attention from the more radical defunding campaign. Last week congressional Democrats proposed a package of sweeping yet traditional police reforms, and a majority of Americans (including Republicans) appear to support it — perhaps because they see it as a more comfortable approach than defunding or abolishing police agencies.

It’s not crazy.

Transferring funding from armed law enforcement to other first responders is not, in and of itself, insane. Even many police would agree that they are the wrong people to deal with mental health crises or Metro fare-evaders. Defunding police does not mean defunding public safety. But at its best it should mean reconsidering the most effective means to attain public safety, how much it should cost, who should pay the freight, and who should do the job.

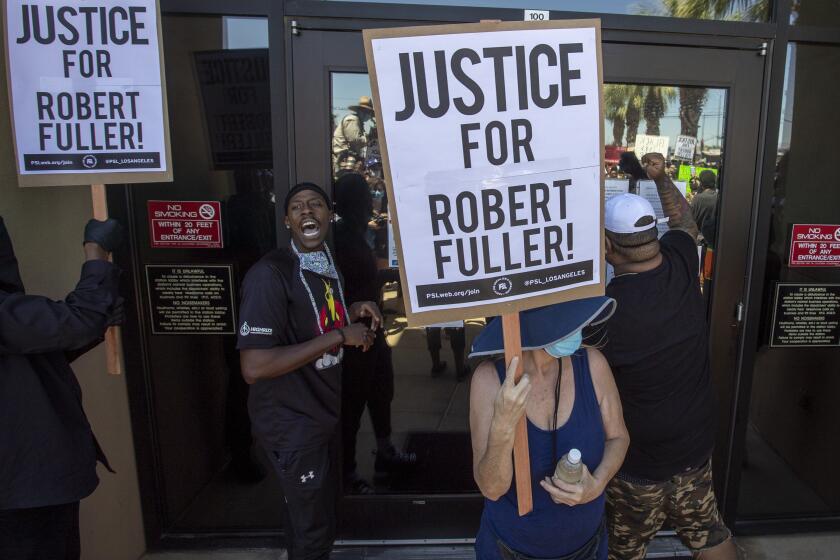

Even if the hangings of Black men in Palmdale and Victorville look at first glance like suicides, there had better be in-depth investigations.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.