- Share via

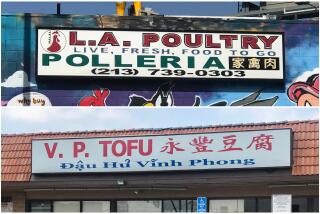

PASO ROBLES, Calif. — Paso Robles is idyllic: Victorians line its streets; wine tasting rooms ring a grassy plaza; country roads wind through oak groves; and grapevines stream like braids over steep hillsides. Children walk to school on their own, and on warm evenings, couples stroll past sidewalk patios where diners enjoy gourmet meals.

But as the setting sun casts golden hues on the quaint wooden shop fronts on the bustling town square one Sunday, the lack of people of color leaves me feeling lonely.

Given that nearly 40% of the population is made up of Mexican Americans and other Latinos, many lured here by jobs in the dozens of surrounding vineyards and wineries, their near-total absence in the square is conspicuous. There isn’t a single Black American besides myself among all of the white pedestrians, either.

I’ve come in a state of dismay to Paso Robles, a city of about 32,000 set between the arid lowlands of the Central Valley and the rugged Pacific Coast.

Across the nation, U.S. history has been drafted into the culture wars. School board meetings in California and elsewhere have devolved into shouting matches over how — or whether — to teach lessons on racial injustice, and over which books about race students should be allowed to study. Some parents argue that their children should be spared the guilt that can result from studying incendiary issues like slavery, white supremacy, segregation, discrimination against Native Americans and immigrants, and the present-day hardships that citizens of color face.

I’d read that a group of parents, students and activists recently fought to reinstate an ethnic studies course at Paso Robles High School after a decade of going without one, only to face detractors who argued that it could inflame racial resentments.

Knowing how challenging it can be for Americans to confide in one another when it comes to matters of race and identity, I suspected there was something deeper going on than a squabble over the merits of a single class, which was eventually adopted and launched in the fall as an elective.

What does it say about Paso Robles, a multicultural city where almost 1 in 5 residents is foreign-born, that a backlash took root here, too?

“We’re here to stay”: Black Californians put down roots in the desert

The complicated reality is that even with the city’s diversity, some people of color feel invisible and that issues of concern to them go ignored, says Susana Lopez, a psychologist and Cal Poly instructor who grew up here in a family of Mexican immigrants. The 38-year-old is raising three daughters with her husband just outside town.

Mel Ruth González, a student in the class who also helped lobby for it, says she and her classmates are learning how easily the mere prospect of Americans of color speaking honestly about their lives — even to foster cultural understanding — puts some citizens on edge.

“My family and myself have integrated into this culture,” says Mel, who was born in the U.S. to parents who emigrated from Mexico. “It would be nice for them to recognize our culture. Why wouldn’t you want to? There’s so many of us here.”

Lopez and other supporters of the class, which the board has unanimously voted to continue next school year, insist their only intent was to honor the spirit of reconciliation that overtook the nation after the police murder of George Floyd, by working to ensure that all of the city’s students feel recognized and valued.

In Orange County racial taunts of students of color, particularly at sporting events, still happen with alarming regularity.

While people of color who live, work and attend school here appreciate the slow pace and small-town charm, many, like Lopez, find it a difficult place to be true to themselves and connect with their roots. Local leaders have tended to emphasize the city’s white pioneer beginnings, often ignoring the Chumash and Salinan people who lived here for centuries before that.

Fieldworkers from the Latino community can be seen in straw hats tending steep rows of grapevines on farms that practically ring the city. They return home to largely segregated neighborhoods on the north and south ends of town — out of sight and out of mind, Lopez says.

One African American explained that many of her fellow Black residents “just stay in line” rather than upset their white friends and co-workers by revealing their experiences with discrimination.

This frustration isn’t felt just by Black residents.

“In this community, which is pretty conservative, it’s like racism doesn’t exist,” Lopez says.

As a Black man in America, I’ve always struggled to embrace a country that promotes the ideals of justice and equality but never fully owns up to its dark history of bigotry, inequality and injustice.

Now, more than any time in recent history, the nation seems divided over this enduring contradiction as we confront the distance between aspiration and reality. Join me as I explore the things that bind us, make sense of the things that tear us apart and search for signs of healing. This is part of an ongoing series we’re calling “My Country.”

— Tyrone Beason

The alienation some in her community live with only worsens when they’re forced to embrace a history of America in which their ancestors’ existence is considered too toxic to teach in school.

“If the history books actually included us, and if the community actually included us, we wouldn’t feel like we had to fit in,” Lopez says.

Regardless of the resistance from critics, she says, “we have to learn how to narrate our own lives.”

::

Mel, a senior, says she’s frustrated. How did a homegrown movement, one that has inspired so many to share their people’s struggles and triumphs, get co-opted into the nationwide mudslinging over critical race theory, a concept originally intended for law students?

Rather than focusing on acts of racism by individuals, critical race theory scholars examine how whole systems and institutions can perpetuate inequities despite the enactment of major civil rights legislation — yet detractors, mostly on the right, argue the concept is used to breed hatred of the United States.

- Share via

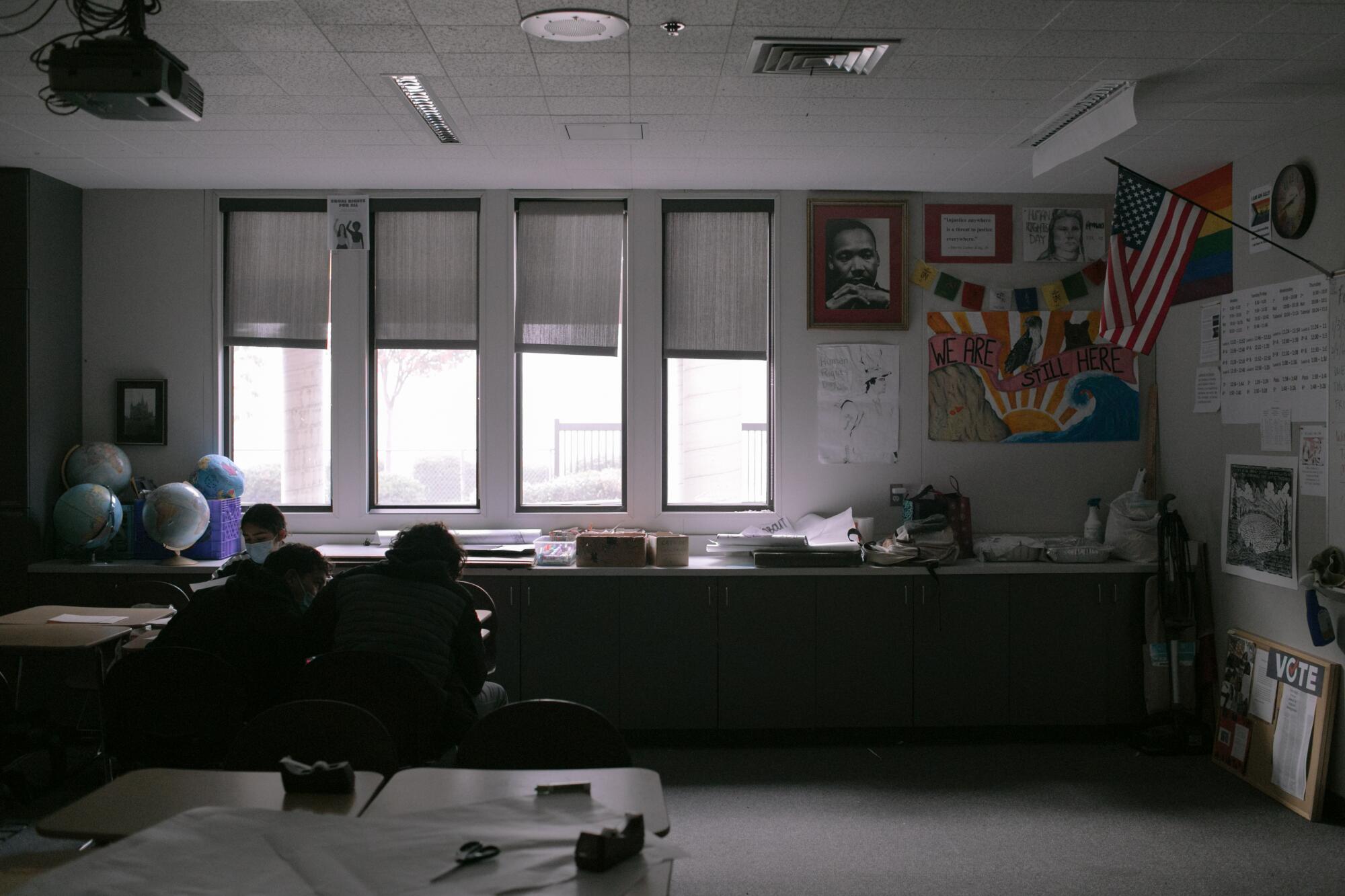

The new ethnic studies course at Paso Robles High has gripped the California town and reignited conversations about race.

“That’s not what we’re doing here,” Mel, 17, says of the idea that her course is linked to critical race theory. “This class is a class to make everyone feel safe, to open up their minds ... and learn about the many ethnic cultures in the United States that helped shape America into what it is today.”

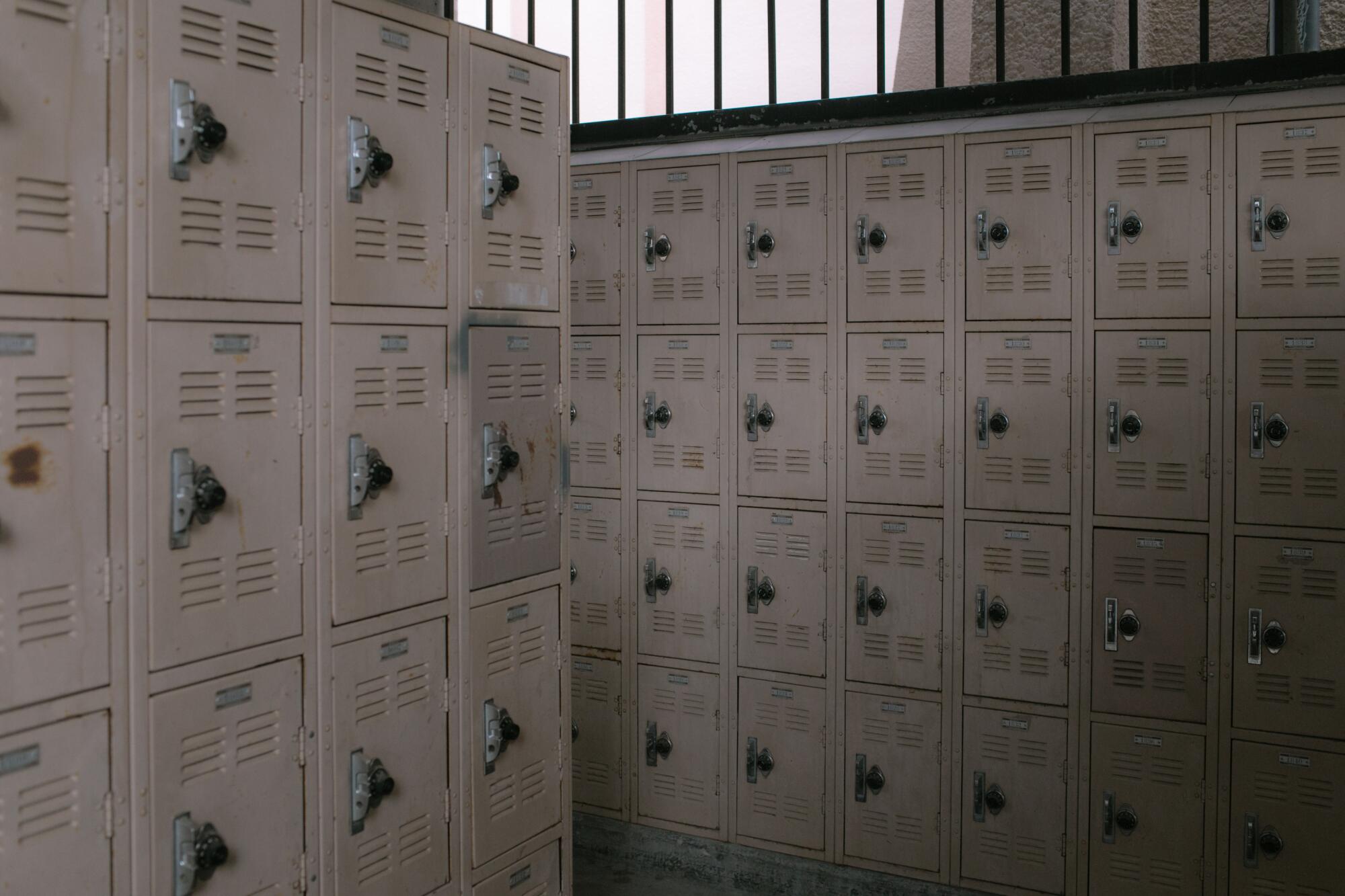

Mel, wearing a white T-shirt with “Choose kindness” on the front, says the need for the class is self-evident given the atmosphere at her school. The student body is half Latino, yet the majority of teachers and school administrators are white. She shared stories about teachers making culturally insensitive remarks, and said she was troubled by recent spasms of racial tension and political conflict on campus.

The tensions aren’t confined to the high school. In November the U.S. Department of Education opened an investigation into accusations that the school district discriminates against Latino parents and community members by not providing language interpreters at hearings and moving to close Lopez’s former elementary school in the majority-minority north side of town where she was raised, among other alleged offenses. The district has denied the discrimination claims.

The instructor presiding over Mel’s class is Geoffrey Land, who has been teaching at Paso Robles High School for 24 years. He started developing the curriculum with input from students, community members and the school board months before California became the first state in the U.S. to require an ethnic studies course in order to graduate.

“It’s difficult to teach a class that’s so much under the microscope,” Land says. “I have community members who’ve asked that there be cameras placed in the classroom.… Parents and board members have been asking for detailed descriptions of assignments, and that’s never happened before.”

One morning Land, who is white, walks the aisles of his classroom as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gazes from a photo on the wall.

“You can talk about this class as an opportunity to continue the work that started 200 years ago to live up to the ideals of our democracy, what Dr. King called the ‘check that came back [saying] insufficient funds,’” he tells his students.

“It’s about this idea of ‘What is America?’ and ‘How do we reckon with our history?’”

He says this knowing that Paso Robles hasn’t necessarily done a good job of reckoning with its own past. A grassy burial site of historic significance to Native Americans sits awkwardly in a Walmart parking lot — preserved after it was accidentally unearthed by construction workers in the 1990s. I only knew where it was because Land had told me.

Not everyone sees the value of exploring history through the lens of identity, Land tells his students as he projects a local newspaper column onto a screen. Its author writes scathingly that the class is an attempt to indoctrinate students with what she describes as critical race theory’s “anti-American” ideas.

Mel and the other dozen students, most of them Latino, react with a mix of amusement, confusion and indignation.

Listening to the teens defend ethnic studies as essential to their growth as citizens, I feel envious. I wish I’d had the chance to take a course like this in high school where classmates felt confident enough to say what was on their minds.

After the class was authorized, Michael Rivera was filled with dread at the prospect of students being exposed to ideas that could make them resent their country or white Americans.

The 68-year-old businessman, who grew up in Los Angeles with parents who emigrated from Mexico, runs a medical equipment firm. He has raised three children in and around Paso Robles. Rivera shared his misgivings at board hearings. He believes that decades of civil rights laws have resulted in a “post-racial” nation where people can succeed if they make the right choices.

“I try to make it clear to people that I’m no victim,” says Rivera, when we speak by phone. “We cannot allow our children to think that we are an irredeemable country.”

During a tour through Lopez’s childhood neighborhood just north of downtown, she says she can’t see how the class could be anything but an enriching experience. While reminiscing at a Mexican bakery that sells shaved ice drinks called raspados, she gazes across the street to the spot where, at the age of 14, she took part in a demonstration for immigrants rights.

“We’re not criminals,” Lopez says her sign read. It breaks my heart to hear how she felt the need to advertise her own fitness to live in this community.

Puerto Rican Kemuel Delgado hates having ‘one foot in and one foot out’ of America. But race wasn’t on his mind when he began pushing for statehood.

She drives past aging apartment buildings and small houses that are a stark contrast to the historic homes with ornate wood trim near the square.

Standing outside Georgia Brown Elementary School, a short walk from her family’s apartment when she was enrolled there, Lopez says she worked alongside her parents at their housekeeping jobs when not studying. One day while scrubbing the floor alongside her mother at an affluent white family’s home, she had a realization.

“I don’t want to clean — why do I have to do this?” she complained in Spanish.

Her mother began to cry, but it took years for Lopez to understand why.

There they were, cleaning floors to put food on their table, yet Lopez’s mother could see in her daughter a determination to pursue a life in which there was no ceiling for her dreams.

Lopez still feels a powerful urge as a Latina to prove her worthiness, especially since some white colleagues in her field have acted surprised that she holds a doctorate.

Later on the phone, we both laugh as she shares anecdotes reflecting her more mundane moments of self-doubt: Growing up, she opted to take bologna sandwiches to school after white classmates made fun of the Mexican dishes her parents would pack for her.

But deep down, she says, it hurts to acknowledge how often she’s attempted to hide even minor details of her identity “just to be seen as ‘American’ — which meant white.”

I confess to her that I’ve bottled up my anger over racist remarks and suppressed the lilting twang of my Southern Black accent countless times in order to prove that I’m nonthreatening and intellectually equal to white Americans.

“It’s painful to lose who you are,” she says, thinking about her girls, who are 10, 6 and 5 months. “I don’t want my daughters to experience that racial trauma.”

::

The most outspoken skeptic of the ethnic studies class has been school board President Chris Arend, a prominent Republican in San Luis Obispo County. He has written and lectured about his belief that systemic racism — a subject I write about all the time — is a left-wing myth.

To his mind, ethnicity matters less in Paso Robles than age-old values such as personal responsibility and looking out for your neighbors.

Arend, who is white, meets me for a conversation in the town square. Sitting together in the shade of a gazebo, we watch sunlight pour through towering trees onto people picnicking in the grass.

In school board races around the country, activists are running against critical race theory.

We drift back in time to his childhood in northern Marin County, and Arend’s face lights up as he recounts watching the civil rights movement play out on TV.

“We cheered; we hooted and hollered because the idea of segregation and all of that stuff was really offensive, pretty repulsive to us,” the 70-year-old attorney says. King is one of his heroes, he says — though the reverend himself referred to “systems of injustice” in some of his speeches.

Arend wears jeans, cowboy boots and two lapel pins on his shirt: One is of the U.S. flag and the other has the Star of David. His mother, who was Jewish, lost her parents in the Holocaust. He understands the horror that can result when people turn on each other over questions of race and identity, and he says he doesn’t want that to happen in the school district under his watch.

Arend was ultimately satisfied enough with revisions to the ethnic studies curriculum to vote for it. Still, he wrote a preemptive ban on critical race theory, which the board approved in August.

America has its problems, he says, but it should be applauded for the strides it has made to bring about racial equality.

I say to Arend that while we both want to see citizens come together, there’s a seemingly unbridgeable chasm. I’m convinced the U.S. can never heal without an unflinching vetting of race relations. He worries that Americans are already too politically polarized to withstand that scrutiny.

Can we ever get past the notion that talking about racial injustice and identity is divisive — or worse, that doing so is anti-white and un-American?

Arend and I let each other’s words sink in. Then his green eyes lock on to me as he reverts to the politics of the moment.

“You, as a Black man, are oppressed, and I am the oppressor?” he asks. “That’s crap.”

The conversations with Arend and Rivera play in my head weeks later when I call child-care provider and Paso Robles High School athletics coach Juanetta Perkins, the Black woman who initially raised the idea of the ethnic studies course for her alma mater and who last summer spearheaded a Juneteenth celebration in the city to commemorate the official end of slavery.

The ethnic studies debate conjures shameful memories about her childhood growing up as one of the few Black children in her classes. She was a beloved athlete at the high school, but she learned few positive details about her heritage there. Like Lopez, she longed to be more like her white classmates, even though some of them had referred to her using the N-word.

“I honestly didn’t understand what ‘Black’ was until I went to Alabama A&M,” Perkins, now 50, says of attending the historically Black university. “I didn’t understand the uniqueness of who I was, and I didn’t understand our history.”

Perkins says she’s “invested in one Paso Robles, where everybody gets along.” But she wonders how any person of color can be expected to let bygones be bygones when racism passes from one generation to another like a cursed hand-me-down.

“My daughter, in the second grade, is called a N—, but you’re worried about your white kids getting offended because of the truth?

“It might be uncomfortable,” she says, her voice bellowing over the phone, as if to a wider audience. “But you need to learn it.”

Perkins believes that Americans owe it to one another to heed a lesson not found in history books but that generations of Black parents have drilled into their children at home:

We can’t know who we are unless we know where we’ve been.

More to Read

About this story

Photo editing and story design by Jacob Moscovitch. This project was edited by John Penner, Millie Quan and Sue Worrel.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.