Why is the coronavirus so much more deadly for men than for women?

- Share via

Men are faring worse than women in the coronavirus pandemic, according to statistics emerging from across the world.

On Friday, White House COVID-19 Task Force director Dr. Deborah Birx cited a report from Italy showing that men in nearly every age bracket were dying at higher rates than women. Birx called it a “concerning trend.”

The apparent gender gap in Italy echoes earlier statistics from other hard-hit countries. While preliminary, early accounts have suggested that boys and men are more likely to become seriously ill than are girls and women, and that men are more likely to die.

Italian health authorities last week reported that among 13,882 cases of COVID-19 and 803 deaths between Feb. 21 and Mar. 12, men accounted for 58% of all cases and 72% of deaths. Hospitalized men with COVID-19 were 75% more likely to die than were women hospitalized with the respiratory disease.

Those figures are in line with early accounts from China, where the novel coronavirus first appeared, and from South Korea, where detection and tracking of coronavirus infections have been very comprehensive.

An analysis of all COVID-19 patient profile studies filed in China from December 2019 to February 2020 suggests that men account for roughly 60% of those who are infected and become sick. And in a detailed accounting of 44,600 cases in mainland China as of Feb. 11, China’s Center for Disease Control reported that the fatality rate among men with confirmed coronavirus infections was roughly 65% higher than it was among women.

Even among children younger than 16, coronavirus may affect boys more than girls. In a recent report on 171 children and adolescents who were treated for COVID-19 at the Wuhan Children’s Hospital, 61% were male.

In South Korea, men accounted for nearly 62% of all cases. And infected men were 89% more likely to die than were women.

If you’ve been infected with the coronavirus, the chances that you will become critically ill depend on many factors.

The emerging picture of male vulnerability to coronavirus may be easily explained by a clear gender disparity with social and cultural roots: Across the world, men are much more likely to smoke cigarettes. That damages their lungs and primes them for inflammation and further damage when they are battling an infection.

In China, where cigarette smoking rates are among the highest in the world, 54% of men were current smokers in 2010, and 8.4% were ex-smokers. Yet only 3.4% of Chinese women had ever smoked, according to the same 2016 study.

In South Korea, the disparity was almost as pronounced: half of adult men and 4% of women smoke. In Italy, 28% of adult males and 20% of females smoke.

But that’s not the whole story, said Dr. Stanley Perlman, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Iowa who has studied coronavirus infection in mice.

In a series of experiments in 2016 and 2017, a team led by Perlman infected male and female mice with the coronaviruses that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). At every age, male mice were more susceptible to infection than females.

At the same time, the death rates of infected female mice shot up when their ovaries were removed, or when they got drugs that suppressed the activity of the hormone estrogen.

To Perlman, those dual findings strongly suggest that there’s something about estrogen that protects against the ravages of deadly coronaviruses — and he suspects it’s true for the new SARS-CoV-19 virus as well.

“Why does estrogen protect the woman, and how?” Perlman said. “We’d like to know.” Estrogen has so many important roles in the female body, “it’s hard to prove anything” about its specific protective powers, he said.

For most other lung diseases, men have a distinct advantage. Women have long been known to suffer complications and die of influenza at higher rates than men. They’re much more likely to develop autoimmune diseases of the lungs. And after accounting for men’s higher rates of smoking, women appear to be more vulnerable than men to lung cancer and emphysema.

“We don’t really understand why that is,” said UC Davis’s Kent E. Pinkerton, who studies gender differences in lung health.

But Pinkerton and others suggest that humans’ responses to COVID-19 could reveal important distinctions between the way that men’s and women’s immune systems fight infection. They suspect that hormonal differences may be playing a key role in that immune response.

And if scientists can uncover how that works, they could identify better strategies for fighting coronavirus infections in general, they said.

Researchers will scour the records of COVID-19 cases for evidence that the immune system’s perimeter defenses — the body’s first response to infection — may react more robustly to this coronavirus in women than in men, said Susan Kovats, an immunologist at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation in Oklahoma City.

If that “innate” immune response tends to be stronger in females, infected women may have more luck keeping their viral loads low, Kovats said. And they may not need to roll out an army of the immune system’s big guns — the T-cells and B-cells — for a major battle.

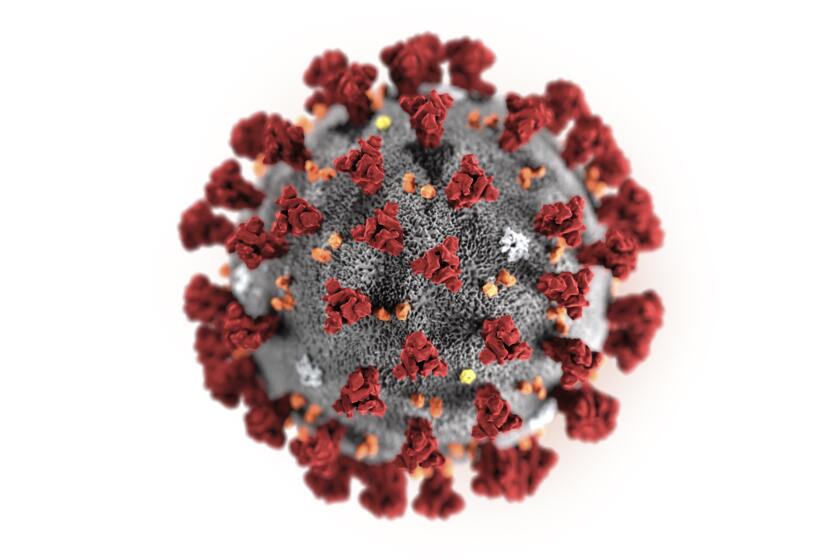

The new coronavirus spreading rapidly around the globe can be deadly because it targets a very vulnerable and essential part of the body — the lungs.

Often, mounting such an assault after viral loads have shot up does double damage, she said. The infection itself damages delicate lung tissue. And then, the “adaptive” immune system overreacts, setting off dangerous levels of inflammation that cause further damage in the lungs.

The result can be death. But if women are thwarting infection earlier and more effectively, they might be less likely to suffer that outcome, Kovats said.

“I’m not surprised” that women’s immune systems may do things in ways that men could learn from, Pinkerton said. For years, immunologists only studied male mammals because the complexity of female hormones muddied their findings, he said.

When it comes to fighting infection, he added, “we really need to study both sexes to understand susceptibility.”