How bad is Omicron? Here’s what to watch for

- Share via

The situation with the Omicron variant is changing so rapidly, it’s hard to know where things stand.

Sometimes the news seems ominous, as when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the strain went from 0.7% to 73% of new infections in the U.S. in just two weeks.

Other times the news seems encouraging, as when South African officials observed that Omicron cases appeared to recede almost as dramatically as they had spiked.

How can we tell what’s really going on? Which indicators will reveal the variant’s true powers?

And when will we know whether Omicron represents a setback in the pandemic, a disaster or an all-out calamity?

Here’s a look at what to watch for.

What’s the worst that could happen?

We could learn that in addition to being roughly 22 times more transmissible than the original coronavirus strain from Wuhan, China, Omicron causes more severe illness, erodes the immunity provided by vaccines or a prior infection, and is resistant to existing treatments.

What about the best-case scenario?

That would be if Omicron infections cause little to no illness in most or all of those who become infected. Even with high transmission rates and a large number of “breakthrough” cases, a variant that caused little more than sniffles or a few days of fatigue might be welcomed as the beginning of endemicity — a state in which the virus remains among us indefinitely. And that could be the beginning of the end of the pandemic.

With the fast-spreading but less virulent Omicron variant, the coronavirus may finally be cutting humanity a little slack.

Is that likely?

For this best-case scenario to materialize, Omicron would need to drop the coronavirus’ nasty habit of causing severe illness and death in people who are elderly or medically fragile. It also would have to stop causing “long COVID” — a mysterious condition with an array of lingering symptoms such as exercise intolerance, sleep difficulties and brain fog — in more than half of those who’ve cleared the virus.

It would be nice, too, if an infection left at least a few months’ worth of immunity in its wake, or conferred long-term immunity after several infections. For a few decades, babies, senior citizens and those with high-risk medical conditions could be vaccinated to prevent severe cases of COVID-19. But eventually, while babies would continue to get the short-term protection of vaccine, most people’s exposure to the virus year in and year out would allow them to weather an infection without much worry.

This is basically the truce mankind has reached with four other coronaviruses that cause what we call the common cold.

What should we be watching for?

Some pieces of the puzzle are beginning to fill in. Researchers from Imperial College London have estimated that Omicron is 5.4 times more likely to cause a reinfection than the Delta variant. That means the impact of any negative trends will be magnified.

How much worse it could be will depend on the next bits of information to fall into place. It’s important to figure out who Omicron infects and in whom it causes severe illness or death.

In addition, knowing when — and for how long — people infected with Omicron are contagious is crucial for keeping the strapped healthcare sector from becoming overwhelmed, said Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

When will we know?

The next two to eight weeks will be critical, said University of Minnesota epidemiologist Michael Osterholm. With its transmission superpowers, Omicron will probably cause a “national blizzard” of cases, he said. No region is likely to be spared, because Omicron is just too good at spreading.

Omicron’s impact on the COVID-19 pandemic will depend on a variety of factors that will take days to weeks for scientists to untangle.

How will we know if Omicron makes people sicker?

In the United States, hospitalizations are the currency by which disease severity is most often judged. Hospital treatment runs the gamut from routine to critical care, and a patient’s journey is usually well documented, compared with being sick at home.

But epidemiologists call hospitalization a “lagging indicator” of a virus’ virulence. Assuming Omicron’s many mutations have not changed the coronavirus’ basic pattern of attack, it usually takes a week or two after symptoms first appear for a COVID-19 patient to become sick enough to require hospitalization. Death typically comes within 30 days, although many patients hold on for longer.

The trend that will begin to tell the story of Omicron’s virulence is a ratio. Researchers will calculate the number of new Omicron infections reported on Day X and compare it with the number of Omicron hospitalizations roughly two weeks later. They’ll also calculate the ratio of new cases reported on Day X to COVID-19 deaths caused by Omicron three to four weeks later.

“We’ll know there’s a problem if that ratio shifts,” Hotez said.

One thing to note: If Omicron is more likely than previous strains to cause asymptomatic infections or extremely mild disease, and those patients don’t get tested, that could throw off the calculation in ways that overestimate Omicron’s ability to make people sick.

What’s happening abroad, and what can that tell us?

The experience of other countries where Omicron has been circulating for longer can offer early clues of what we could be in for. But differing healthcare systems, vaccination status and population demographics make the comparisons imperfect.

This week, the World Health Organization reported that hospitalizations in South Africa and the United Kingdom continue to rise, and said it was “possible” their healthcare systems would be overwhelmed. But the WHO also noted that data on the clinical severity of Omicron infections are “still limited.”

Earlier data from South Africa suggested Omicron infections might cause milder disease and result in less need for supplemental oxygen and hospitalization. And a preliminary study released Wednesday on the science-sharing site MedRxiv found that vaccinated South African healthcare workers who had breakthrough infections involving Omicron were a bit less likely to require intensive hospital care than those whose breakthrough infections were caused by the Delta or Beta variants.

The U.K. Health Security Agency this week reported 45,145 confirmed Omicron cases in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, with 129 hospitalizations and 14 deaths probably attributable to the new strain. But cases could readily be three times as high, the agency acknowledged. That uncertainty about how many Omicron cases there really are makes it tricky to pin down a neat ratio of cases to hospitalizations.

What would it mean if Omicron sickened different groups of people?

Are men still slightly more likely to die than women? Is COVID-19 still a disease most likely to cause illness and death in elderly people? Are asymptomatic infections still typical in children? Over the coming weeks and months, researchers will scour medical records and revisit existing groups of study participants to find answers to questions like these.

They’ll also watch for changes in the way Omicron infections play out to see whether hallmark symptoms like runaway inflammation, blood-clotting abnormalities and lung damage remain key features of COVID-19. These findings could point to important factors that make some people more vulnerable to Omicron, and thus in greater need of vaccine protection.

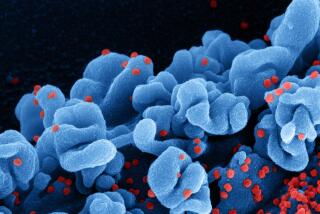

The Omicron variant was probably incubated in a person with poorly controlled HIV who struggled to clear a coronavirus infection.

What about children?

South African researchers reported early on that children appeared more likely to be hospitalized if they were infected with Omicron — a trend that would depart from past variants, and will be closely watched.

If younger patients generally remain less likely to become ill, it will be important to establish whether they nevertheless remain effective virus spreaders.

Will vaccines still work?

Lab tests on Omicron have already indicated that the blood serum of vaccinated people is less able to stop the virus from invading cells. But real-world data will be needed to confirm and flesh out those lab findings.

If people who are vaccinated and boosted begin filling up hospitals and dying, that will be grim evidence that vaccine protection has been gravely undermined. So far, the CDC says two doses of mRNA vaccine appear to reduce the risk of severe illness with Omicron. But officials stress that adding a booster shot will strengthen that protection, and they’re urging vaccinated Americans to get one if they’re eligible.