Here’s what scientists know about BA.2, the ‘stealth’ version of Omicron

- Share via

Scientists and health officials around the world are keeping their eyes on a descendant of the Omicron variant that has been found in at least 40 countries, including the United States.

This version of the coronavirus, which scientists call BA.2, is considered stealthier than the original Omicron because its particular genetic traits make it somewhat harder to detect. Some scientists worry it could also be more contagious.

But they say there’s a lot they still don’t know about BA.2, including whether it evades vaccines better or causes more severe disease.

At least two cases involving BA.2 have been identified in Santa Clara County, said Dr. Sara Cody, the county’s health officer and public health director.

“We don’t really know what that means yet. We’ll be learning that in the days and weeks to come,” she said. “So far, we don’t really know how it behaves.”

Early data from Denmark, where BA.2 has been spreading rapidly, suggest little reason for added concern, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious diseases expert at UC San Francisco.

“You never know what’s going to happen,” he said. “But I’ll be shocked if it makes you sicker.”

Here’s a closer look at what’s known so far about BA.2.

Where has it spread?

Since mid-November, more than three dozen countries have uploaded nearly 15,000 genetic sequences of BA.2 to GISAID, a global platform for sharing coronavirus data. As of Tuesday morning, 96 of those sequenced cases came from the U.S.

“Thus far, we haven’t seen it start to gain ground” in the U.S., said Dr. Wesley Long, a pathologist at Houston Methodist in Texas, which has identified three cases of BA.2.

The variant appears much more common in Asia and Europe. In Denmark, it made up 45% of all COVID-19 cases in mid-January, up from 20% two weeks earlier, according to Statens Serum Institut, which falls under the Danish Ministry of Health.

What’s known about it?

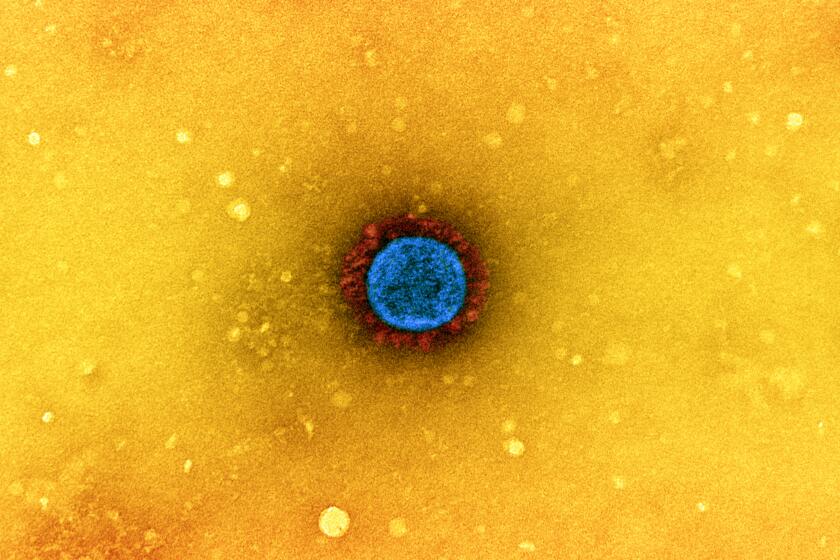

BA.2 has lots of mutations. About 20 of them in the spike protein that studs the outside of the virus are shared with the original version of Omicron. But BA.2 also has additional genetic changes not seen in the initial version.

It’s unclear how significant those mutations are, especially in a population that has encountered the original Omicron, said Dr. Jeremy Luban, a virologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

World health officials are offering hope that the ebbing of the Omicron wave could usher in a new, more manageable phase of the COVID-19 pandemic

For now, the original version, known as BA.1, and BA.2 are considered subsets of Omicron. But global health leaders could give BA.2 its own Greek letter name if it is deemed a globally significant “variant of concern.”

The quick spread of BA.2 in some places raises concerns it could take off.

“We have some indications that it just may be as contagious or perhaps slightly more contagious than [original] Omicron since it’s able to compete with it in some areas,” Long said. “But we don’t necessarily know why that is.”

An initial analysis by scientists in Denmark shows no differences in hospitalizations for BA.2 compared with the original Omicron. Scientists there are still looking into this version’s infectiousness and how well current vaccines work against it. It’s also unclear how well treatments will work against it.

Doctors also don’t yet know for sure if someone who’s already had a coronavirus infection caused by Omicron can be infected again by BA.2. But they’re hopeful that past experience with Omicron might lessen the severity of disease if someone later contracts BA.2.

When the coronavirus attacks the body, the immune system steps up, trying to respond quickly and powerfully enough to stop the virus from running wild.

The two versions of Omicron have enough in common that it’s possible that infection with the original variant “will give you cross-protection against BA.2,” said Dr. Daniel Kuritzkes, an infectious diseases expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Scientists will be conducting tests to see whether antibodies from an infection with the original Omicron “are able to neutralize BA.2 in the laboratory and then extrapolate from there,” he said.

How concerned are health agencies?

The World Health Organization classifies Omicron overall as a variant of concern, its most serious designation, but it doesn’t single out BA.2 with a designation of its own. Given its rise in some countries, however, the agency said investigations of BA.2 “should be prioritized.”

The U.K. Health Security Agency, meanwhile, has designated BA.2 a “variant under investigation,” citing the rising numbers found in the U.K. and internationally. Still, the original version of Omicron remains dominant in the U.K.

Why is it harder to detect?

The original version of Omicron had specific genetic features that allowed health officials to rapidly differentiate it from Delta using a certain PCR test because of what’s known as “S gene target failure.”

BA.2 doesn’t have this same genetic quirk. So on the test, Long said, BA.2 looks like Delta.

“It’s not that the test doesn’t detect it; it’s just that it doesn’t look like Omicron,” he said. “Don’t get the impression that ‘stealth Omicron’ means we can’t detect it. All of our PCR tests can still detect it.”

The Omicron surge has peaked, rather unevenly, in California. But there’s one wrinkle — the emergence of a subtype called BA.2.

What should you do to protect yourself?

Doctors advise the same precautions they recommend for Omicron: Get vaccinated and follow public health guidance about wearing masks, avoiding crowds and staying home when you’re sick.

“The vaccines are still providing good defense against severe disease, hospitalization and death,” Long said. “Even if you’ve had COVID 19 before — you’ve had a natural infection — the protection from the vaccine is still stronger, longer lasting and actually ... does well for people who’ve been previously infected.”

The latest version is another reminder that the pandemic hasn’t ended.

“We all wish that it was over,” Long said, ”but until we get the world vaccinated, we’re going to be at risk of having new variants emerge.”

Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.