- Share via

The murder of Claire Penelope Hough was the kind of mystery that keeps homicide detectives awake at night, pulling at loose threads.

For almost 30 years, they’d tugged and tugged and couldn’t unravel it. Now they wanted to try again.

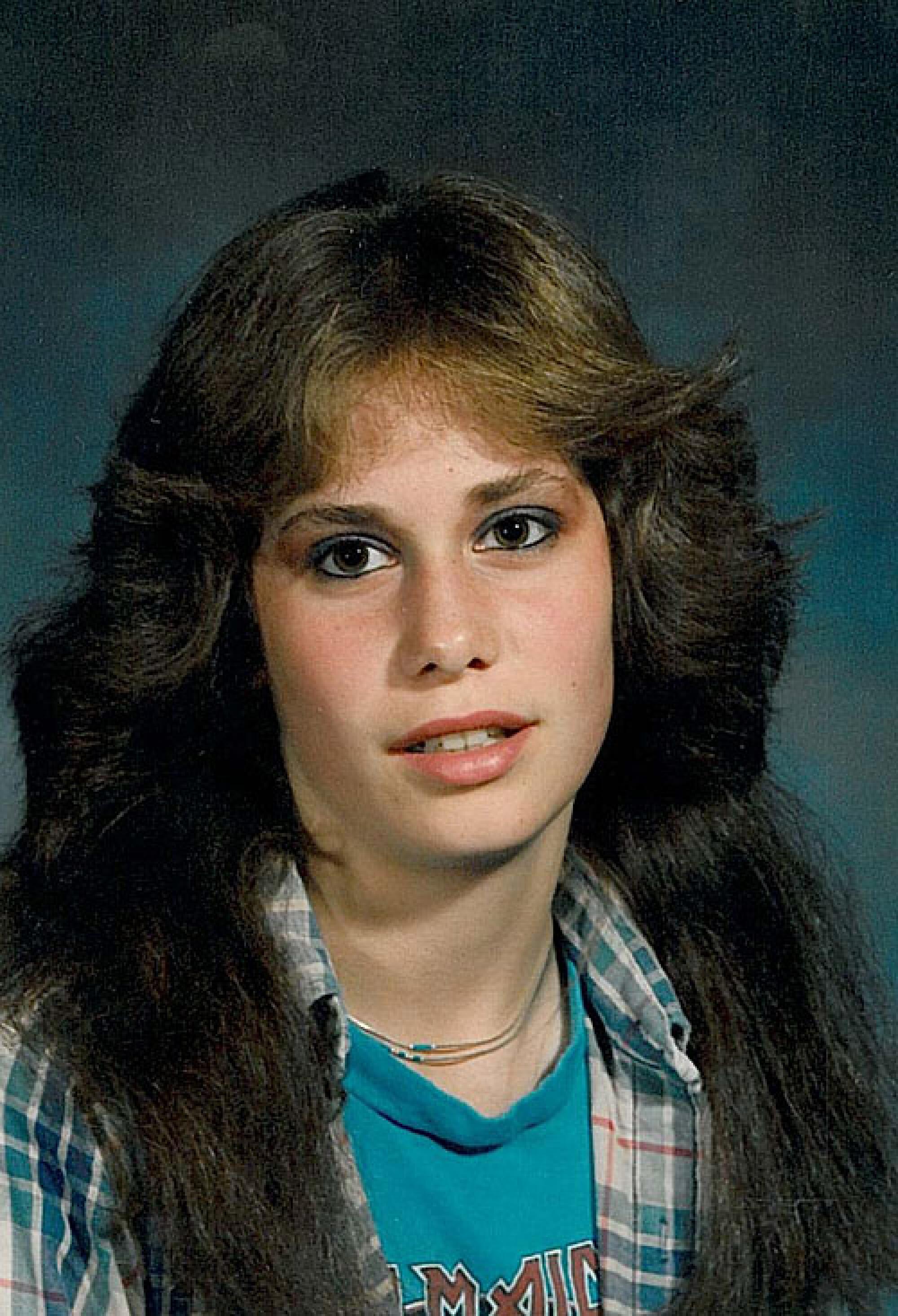

Their persistence was due partly to Hough’s age — a month shy of 15 when she was sexually assaulted and strangled on an August night in 1984. Cops have teenage daughters too.

Part of it was the savagery of the attack at Torrey Pines State Beach. She was battered in the face and slashed on the neck. Sand was stuffed down her throat. Her left breast was cut off.

Detectives pressed Kevin Brown to confess to 1984 sexual assault and killing.

So yes, they wanted to catch this monster, even as the years ticking by made that more difficult. Time is no ally to crime-solvers: evidence degrades, witnesses die, detectives are assigned to other cases.

But as the calendar advanced, so did science.

Every couple of years, new techniques or equipment would come along, offering hope to cold case detectives working unsolved murders. They would retrieve old items stored in evidence rooms and ask the forensic scientists to have another go.

So it was in the summer of 2012 that Lynn Rydalch, a San Diego Police Department homicide detective, sent an email about the Hough murder to the department’s lab.

“I don’t want to leave any stone unturned,” he wrote. “Any ideas you have for something that might have been missed would be greatly appreciated.”

The request went to criminalist David Cornacchia. He’s an expert in DNA, the increasingly sophisticated identification of criminal suspects from even the tiniest bits of blood, saliva and other bodily fluids. Since its introduction in the late 1980s, it has revolutionized crime-solving, considered so irrefutable as evidence that it spawned a maxim: “DNA don’t lie.”

Earlier tests done over the years on clothing and other evidence located stains that appeared to be from humans. But the lab never had enough material to link it to anybody.

This time, using more powerful tools, Cornacchia extracted DNA, amplified it, and created a genetic profile. He ran it through law enforcement databases to see if there was a match.

In Hollywood movies, television cop dramas and true-crime podcasts, this is the swelling moment of delicious truth. Lady Justice rebalances her scales and reaches across the decades to tap a bad guy on the shoulder.

Sometimes she taps in real life too.

Blood spots on Hough’s jeans and underwear came back to a felon named Ronald Tatro. His criminal record included raping a woman at knifepoint in Arkansas in 1974 and attempting to kidnap a teenager in La Mesa, Calif., in 1985 after zapping her twice with a stun gun. He once checked himself into a psychiatric clinic, troubled by his inability to control violent urges.

Finally, it seemed, the planets had aligned to solve Claire Hough’s 28-year-old murder.

But there was a complication.

Cornacchia also got a DNA hit on vaginal swabs collected all those years ago during the girl’s autopsy. And it wasn’t Tatro.

The sperm cells belonged to someone familiar to the crime lab. He used to work there.

‘A very pleasant person’

Kevin Brown grew up in Sacramento, the youngest of two children. His father was a podiatrist, his mother an administrative assistant in state government.

He went to Cal State Sacramento and got a bachelor’s degree in forensic science. After he graduated, in 1979, he started working as a criminalist for the New Mexico state police.

Brown liked the job but not the location. He was a Californian at heart. Three years in, he moved to the San Diego police lab. He stayed for 20 years, rotating through various units — narcotics, firearms, serology, trace evidence — before leaving in 2002.

A decade later, his DNA showed up in the Hough case. And it stunned the police lab.

Manager Jennifer Shen and other supervisors huddled behind closed doors, trying to figure out what the result meant and what to do about it.

Shen knew Brown. They had been in the same lab for seven years at the beginning of her time there and the end of his. She remembered him as “a very pleasant person” and had enjoyed their office interactions.

It was upsetting to think that one of their own could be a murderer — especially someone who was by all accounts mild-mannered, even timid. Brown was 6 feet 4 but not imposing.

He was someone whose bosses dinged him in evaluations for becoming rattled and tongue-tied during courtroom testimony. One female criminalist considered him “weak-jellied” and said, “I could beat the crap out of him myself.”

But if Brown didn’t have it in him to assault Hough, that meant his DNA wound up in the evidence through contamination, a prospect that presented its own worries to lab management. It would make them look bad, raise questions about the integrity of the work there.

Inadvertent contamination happens with surprising regularity in crime labs. Technicians brush up against a bicycle or cough over a handgun and their DNA winds up in the mix. They pick up a pen used by someone else, and transfer that person’s DNA onto a piece of evidence down the line.

That’s why Brown and other criminalists provide genetic samples for the law enforcement database, to weed out mistakes when they happen.

But Brown’s DNA in the Hough case wasn’t from wandering skin cells or droplets of saliva. It was sperm, on vaginal swabs. Lab managers had never encountered such a thing.

They understood how it could happen, in theory. It’s little-known outside labs, but criminalists routinely keep their own semen at work, deposited on small pieces of cloth known as standards. The samples are used to make sure test chemicals are properly detecting the presence of sperm.

If an analyst somehow brought a semen standard in contact with a piece of evidence, that could cause contamination.

The lab managers couldn’t imagine anyone being that sloppy. Even in 1984, before anyone knew anything about super-sensitive DNA testing, criminalists understood they had to be careful.

But the supervisors trying to figure all this out weren’t in the lab back then, when it was not just in a different era but in a different building. They didn’t know how the semen standards were stored, or how the criminalists cleaned their tools, or even whether they always wore masks or gloves.

They didn’t ask, either, because they didn’t want word of Brown’s DNA hit spreading in the office.

They did know this, however: Brown wasn’t the analyst who examined the Hough evidence in 1984. That was John Simms, a criminalist respected by his peers for his thoroughness.

Simms, still in the lab and serving as its quality assurance officer, was mortified by the idea that something he’d done might have messed things up. Had he used Brown’s semen standard instead of his own? He told Shen he didn’t think so, although he couldn’t recall working the case. There had been so many over the years.

The lab managers were in a quandary. Should they tell the cold case detectives about Brown’s DNA, or write it off as contamination, even though they doubted that’s what happened? Dismissing it would allow police to tie Tatro, the convicted rapist, in a tidy forensic bow.

Shen and the others decided to put it all on the table. Let detectives investigate. Maybe they would find more evidence tying Brown to the crime. Maybe they would connect him to Tatro, figure out how the two of them wound up together on the beach with the girl. Maybe they would find more reasons to suspect contamination.

“We were in a very difficult spot,” recalled Patrick O’Donnell, the supervisor in charge of DNA testing. “We needed to disclose this result but do it in a way that provided a complete set of explanations as to why we are seeing this result. That was our obligation.

“Had we covered up this result, and then three years later there is additional evidence that Kevin Brown somehow was a serial killer, then we would not have done our duty.”

The idea of a serial killer wasn’t idle speculation. Six years before Hough’s murder, another teen, Barbara Nantais, 15, had been murdered on the same beach, and in the same manner: sexually assaulted, beaten, mutilated, strangled.

Her slaying was unsolved too.

Only one explanation?

Normally criminalists let detectives know by phone when DNA results are in. This time they did it in person.

The meeting was held in the fall of 2012, in a location that spoke to how thorny the case was: a conference room in the police chief’s office.

Shen attended, along with O’Donnell. Rydalch, the cold case detective, was there with his boss.

No written record of the meeting is known to exist. The lab managers would say later that they told the detectives this: They believed contamination had not occurred, that it would have required a “colossal breach of protocol,” but they couldn’t rule it out. It’s always possible.

That’s not what the detectives heard. They left the meeting certain that the scientists had explored and eliminated contamination, leaving only one explanation for Brown’s sperm: sexual contact.

- Share via

Detective Michael Lambert discusses what he was told about contamination.

And that’s the message they passed along a few days later to detective Michael Lambert, who had just joined the cold case team. He inherited the Hough file from Rydalch, who was retiring.

Born in Berlin, the son of an Army soldier, Lambert grew up on the East Coast and joined the Navy after graduating from high school. He served five years and then joined the San Diego police academy in 1989 at age 25.

He’d wanted to be a cop since childhood — a friend’s uncle was an officer — but not just any cop. On the first day of the academy, when recruits stand up and share their hoped-for futures, he talked about becoming a homicide detective.

About 12 years into his career, he got his wish. He’d done stints by then in patrol, narcotics and as a generalist in the detective pool. He worked murders for about a decade before moving to the cold case team.

He immersed himself in the Hough file, which numbered thousands of pages. He learned that the teen was from Cranston, R.I., the youngest of two children in a middle-class family.

She was entering 10th grade, a bright girl who didn’t care much for school. She liked poetry and the bands KISS and Van Halen. She would stick up for people she thought were being picked on, and sometimes do or say things to shock others. She smoked Marlboro Lights and had a boyfriend back home who was four years older.

In August 1984, Hough came out to San Diego with a friend. They stayed in Del Mar Heights with Hough’s grandparents, a 15-minute walk from Torrey Pines State Beach, which they visited almost daily. They sat on towels on the sand near a bridge, listening to music from a portable radio/cassette recorder.

Her friend returned to Rhode Island after they had been there for about a week. Without her companion, Hough told her grandparents she was bored. On the night she was killed, she slipped undetected out of the house and walked to the beach, stopping at a Circle K to buy cigarettes. The clerk there thought she looked 20, not 14.

Around 5 the next morning, a man collecting aluminum cans on the beach swept his flashlight across what he assumed was someone sleeping. She was on her right side, on a white towel, her sandals off. When he saw the blood, he called police.

The beachcomber’s name was Wallace Wheeler, a self-proclaimed psychic with schizophrenia who had recently been arrested as a “peeping Tom.” Police considered him a suspect, especially after he began sending weekly letters to Hough’s parents, sharing visions he had of the killer as a long-haired man who was missing an ear.

At the urging of detectives, the Houghs played along for a while, in case Wheeler decided to confess. He never did.

Four years later, he killed himself, jumping from the 13th floor of an apartment building in San Diego.

The rapist

The forensic lab’s double DNA hit left Lambert with questions as he began to investigate: How did Ronald Tatro, a convicted rapist, and Kevin Brown, a former police employee with no criminal record, ever meet, let alone commit a murder together?

Or were they lone wolves who just happened to prey on the same girl at the same place at the same time?

The detective flew to Minnesota to interview the friend who had been in San Diego with Hough. He showed her photos of the two men, taken around the time of the killing, when Tatro was 40 and Brown was 32.

She didn’t recognize either one. Lambert showed her a photo of the van Tatro was driving back then — nothing there, either.

The friend, Kimberly Jamer, told him Hough was faithful to her boyfriend — they talked about everything, she said — and would not have been interested in men that old. The only people they met in San Diego were teens around the same age hanging out at the beach, and that was just in passing.

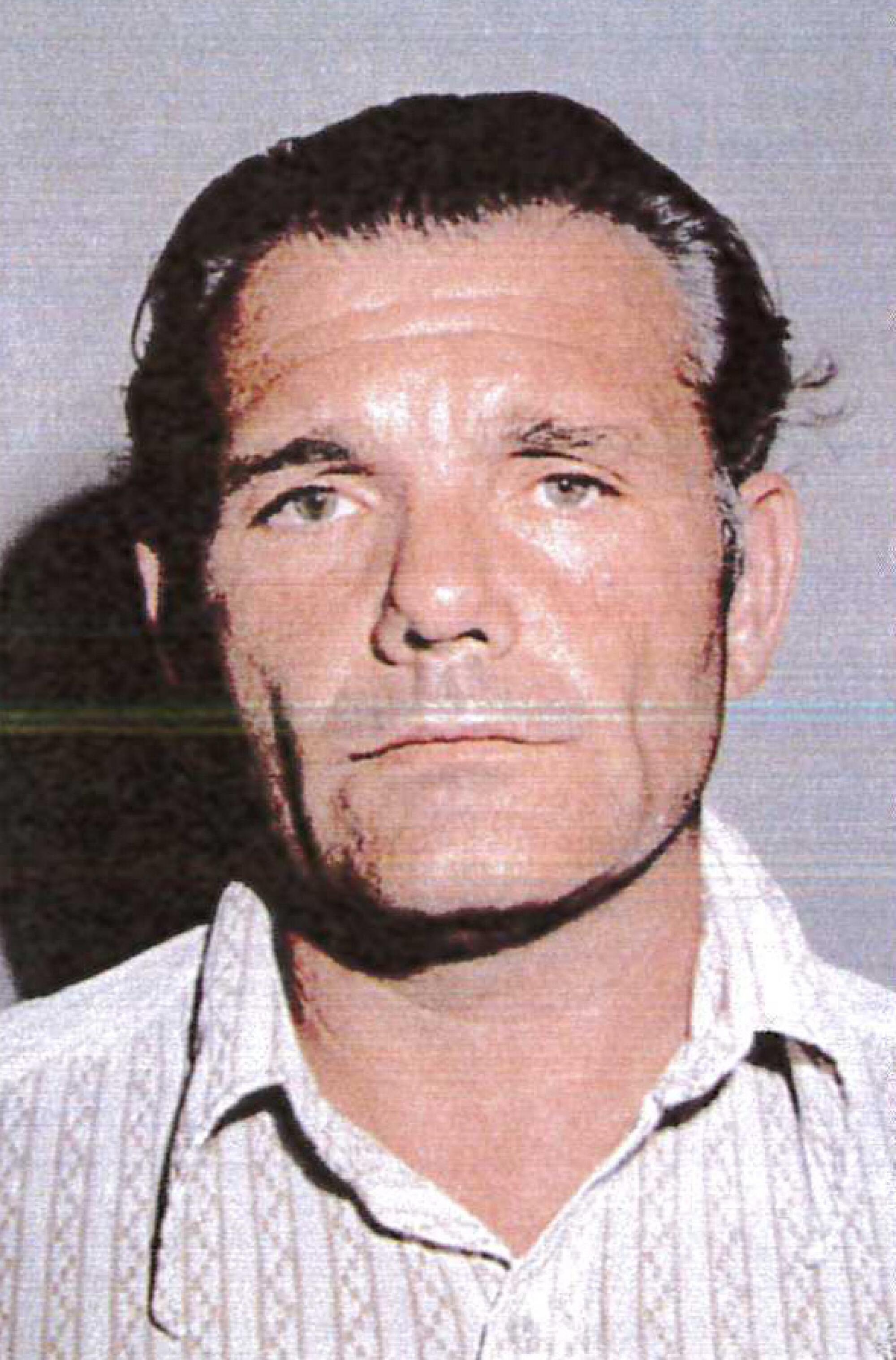

Lambert and his partner, Lori Adams, looked into Tatro’s history. Born in Elmhurst, Ill., he made it through the 10th grade before dropping out and later earning a GED. He was divorced and had two children. He served six years in the Army, in two separate stints, and blamed a “run-in” he had with a female service member for his subsequent crimes.

In 1974, in Arkansas, he lured a store clerk to his car, shoved her in the trunk and drove to an isolated area. He stuck a knife in her mouth and raped her. Prior to being arrested, he went to a psychiatric clinic in Hot Springs, telling the doctor this wasn’t his first offense and that he had no control over his compulsions.

Sentenced to 40 years, he served eight and was paroled to San Diego, where his sister lived. He worked as a handyman, doing maintenance work for apartment owners and real estate agents.

In September 1984, one month after Hough was murdered, Tatro was investigated by San Diego police for his possible involvement in the murder of Carol DeFelice, a prostitute. He was never charged in that case.

Then, in June 1985, a 16-year-old girl whose car had broken down on University Avenue in La Mesa was offered help by a man in a blue van. After she got in, he tried to subdue her with a stun gun and ordered her to sit between the seats. She screamed, fought him off, and escaped, memorizing the van’s license plate number as she fled.

The plate was registered to Tatro. Police found him at his sister’s house, in the back of the van. He was naked on the floor, bleeding from both wrists. Two razor blades were nearby, as was a pornographic magazine depicting bondage and sadomasochism. He’d written a note leaving all his possessions to his sister.

He was taken to a hospital, and then to court, where he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. “I want psychiatric help,” Tatro told a probation officer, “and I want to live a normal life.”

When he got out of prison, he was sent back to Arkansas for violating his parole there and eventually wound up in Tennessee. On Aug. 24, 2011 — 27 years to the day after Hough’s body was found — Tatro drowned in what authorities ruled a boating accident on a river.

Was the date a coincidence, or a message? Tatro’s hat, glasses and wallet were still on the boat, tucked away safely. Officials said it appeared he went into the water on purpose.

If it was a suicide, it was the second one involving someone associated with the Hough case. And not the last.

Sweating the suspect

In every one of Tatro’s crimes, he acted alone, a possible red flag for detectives trying to connect him to Kevin Brown, the criminalist.

Or not.

Lambert’s experience working all sorts of cases, from low-level misdemeanors to murder, taught him that “there are many times where people acted alone when they were out there, and then there are instances where those same people who act alone in crimes will also act in concert or with other people in other crimes.”

So detectives kept looking for links, and began making plans to search one place where they thought they might find them: Brown’s house.

Although the criminalist had left the San Diego Police Department a decade before his DNA showed up in the Hough case, he was still in the area. He shared a two-story, three-bedroom home in Chula Vista with his wife, Rebecca, her mother, and one of her brothers.

After quitting his SDPD job — his bosses had made it clear his difficulty on the witness stand jeopardized his continued employment — he returned to New Mexico and the state crime lab for a few years. Then he and his wife came back to San Diego, where he worked in an electronics store until he was 55, old enough to begin drawing his police pension.

Lambert expected at some point to try to interview Brown, but he worked around the edges first, talking to criminalists who knew him from the lab.

He learned things that roused his suspicions.

Brown had a nickname among co-workers: “Kinky Kevin.” It stemmed from a fondness for strip clubs and nude photography, activities he pursued during his first decade here, while he was a bachelor.

Several of his former colleagues told Lambert that Brown didn’t just go to strip clubs — he bragged about the visits. They said Brown also regaled them with tales of organized photo shoots involving naked models, including one in a hotel that was raided by the vice squad. He once asked a female employee to pose for him.

Annette Peer, a retired criminalist who found Brown “creepy,” said she was alone with him in the lab one day when he started reading out loud from a police report. Criminalists did this from time to time, laughing at sections they found odd or amusing.

There was nothing funny about the report Brown had, Peer told the detective. It detailed a sexual assault, “very violent.” Peer couldn’t understand why Brown had the report in his desk, let alone why he chose to share it with her.

Peer said Brown also brought a pornographic movie to work one day and showed it to several male colleagues.

Strippers, nude models, porn — Lambert wondered if those were the shadowy worlds where Brown and Tatro met. Birds of a feather?

By the end of 2013, the detectives were ready to approach Brown directly.

A confession is often the most powerful evidence prosecutors present in a criminal trial, so detectives work hard to obtain them. Lambert told Peer that he might have to “sweat” Brown to close the case. (“God, I wish I could be a fly on the wall,” she replied.)

Lambert also sought permission to search Brown’s house. In early January 2014, he filed a 34-page affidavit outlining the history of the case, the DNA results and the “Kinky Kevin” stories. It said the crime lab had determined that contamination “is not possible” as an explanation for Brown’s sperm showing up in the evidence.

Superior Court Judge Frederic Link signed the warrant. It authorized police to take cellphones, computers, newspaper clippings, photographs and other items that might have information relating to Hough, Tatro or the murder investigation.

A team was assembled. About a dozen police officers waited outside while Lambert and Adams walked to the front door.

They had not informed Brown they were coming. He didn’t know he was under investigation.

Brown answered the knock on the door. It was about 8:30 a.m. and he was still in his pajamas and robe. “Good morning,” he said, and allowed them in.

Lambert said they wanted Brown’s help with some old homicide cases involving prostitutes. He showed Brown a photo of one of the victims, killed in February 1984. Brown didn’t recognize her.

There’s a man we believe might be involved in the murder, the detective said. Maybe you know him.

The man was Tatro. The detectives said he had been contacted by police in September 1984. That would have been one month after Hough was murdered. He was parked in a Dodge van on El Cajon Boulevard, in an area frequented by prostitutes, they said.

An officer filled out a field interview card, and on the back scrawled a note: Tatro said he knows a SDPD employee named Kevin Brown.

None of that was true. There was no police stop, no field interview card, no claim by Tatro that he knew Brown.

This is known as a ruse, and it has been deemed legal by the courts. Police can lie to a suspect while pursuing a confession, as long as they don’t cross the line into illegal coercion. But just where to draw that line is controversial, and several states — Oregon, Illinois, New York — have passed or proposed laws to curtail falsehoods.

The detectives showed Brown a photo of Tatro and another one of his van. “Maybe you were buddies at the time or something like that,” Lambert said, suggesting the two might have met at a strip club or a bar.

“It doesn’t ring a bell,” Brown said.

“You must have had some kind of interaction with him,” Adams said.

Brown: “I don’t know how he got to know me.”

“For him to to drop your name,” Lambert said, “obviously he knew you existed and obviously he knew that it was a police employee, because how else would he know that if you had never met?”

Brown kept looking at the photo, racking his brain. He mentioned the nude photography, wondered if maybe Tatro had been taking pictures too. They talked about that for several minutes, the detectives asking for details about whether the models were also strippers or prostitutes.

The detectives said Tatro was someone who targeted young females. They mentioned the La Mesa stun gun case and asked Brown if maybe that jogged his memory. It didn’t.

“We feel pretty confident this guy is probably good for some other cases,” Lambert said. “That’s our big reason for trying to find somebody that may have known him back then that would be able to give us some kind of insight as to the type of person he was.”

Brown went to his computer and looked up the name of a man who organized the nude photo shoots. He suggested detectives contact that guy to get a line on Tatro.

Then Lambert said they were looking at Tatro in connection with a particular case. He showed Brown a photo of Claire Hough.

“Oh,” Brown said, “I remember her.”

This article was compiled from thousands of pages of police reports, court filings, sworn depositions and trial transcripts. Unless otherwise noted, the quotes used are from those records.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.