- Share via

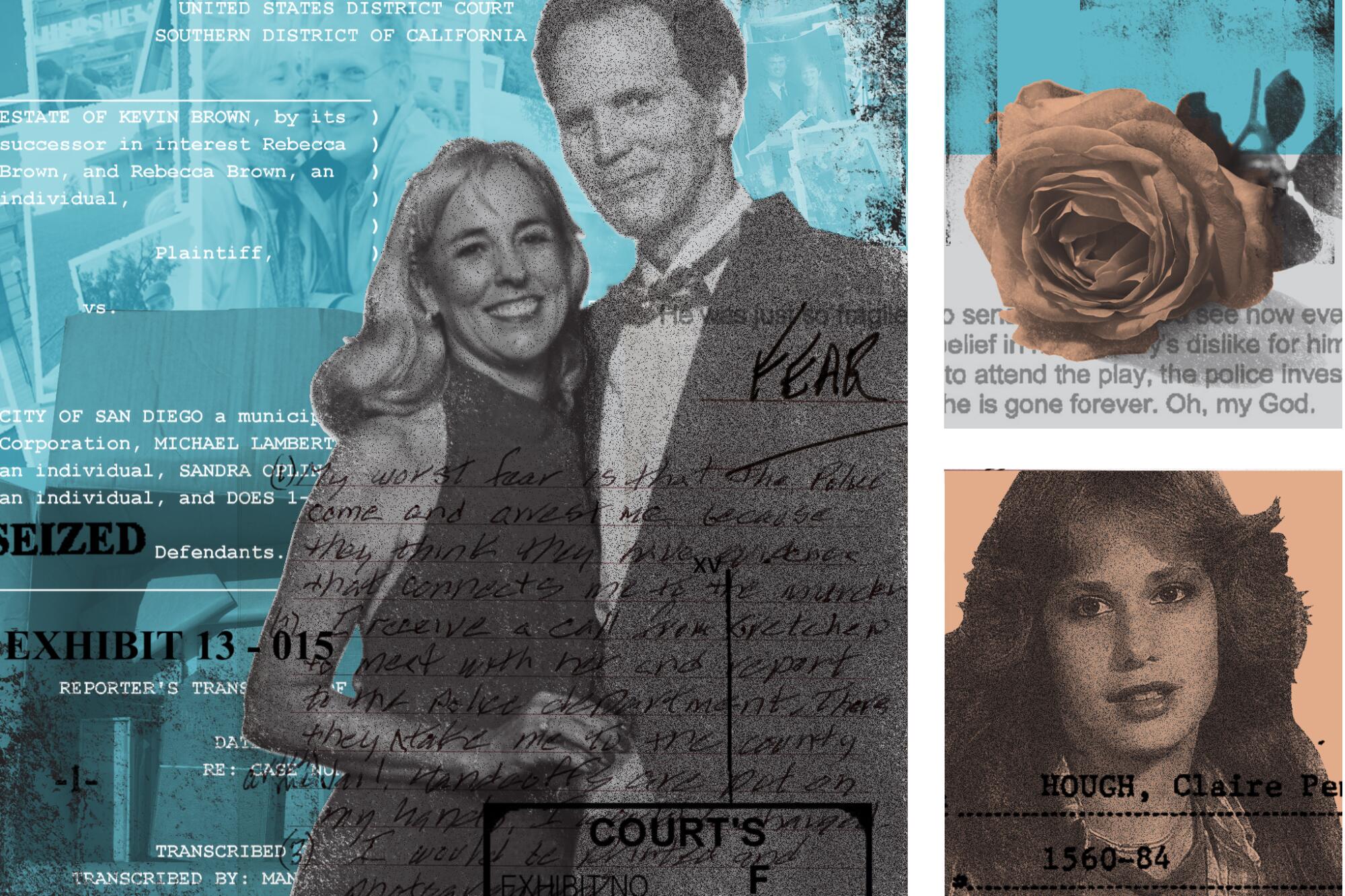

Two days after her husband hanged himself, Rebecca Brown went to a mortuary to make final arrangements. She was awash in grief and fury.

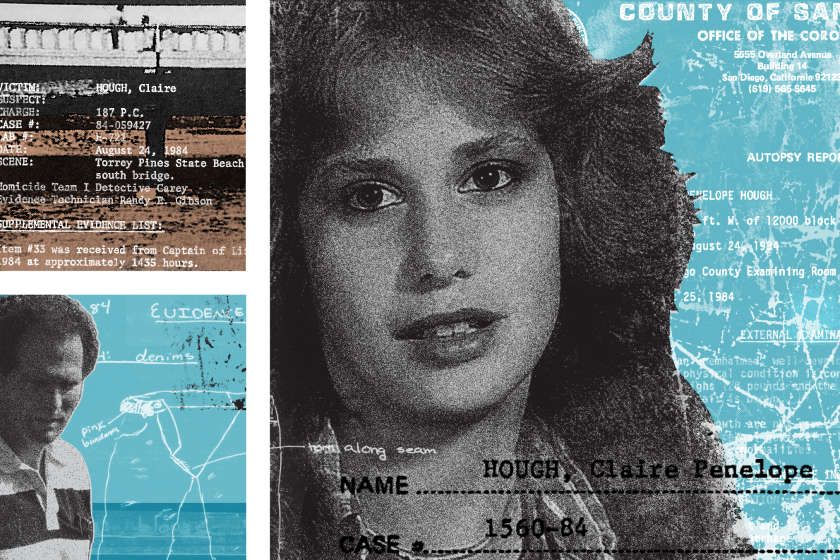

She felt her spouse of 21 years, Kevin Brown, had been driven to suicide by San Diego police detectives investigating the 1984 murder of a 14-year-old girl at Torrey Pines State Beach.

When she got home from the mortuary, on Oct. 23, 2014, her despair mounted. There was a phone message from a news reporter, asking about a news release police had issued about the murder case. It said Kevin Brown had killed himself as “preparations were being made” for his arrest.

Thirty years after Claire Hough was killed, a new round of forensic testing pointed to two suspects. One of them was familiar to the police.

His widow phoned then-Chief Shelley Zimmerman’s office several times and asked for a retraction.

“I was very angry,” she recalled later, “because they kept trying to pin this on him when he was alive, and they never could, never did. They never arrested him. And once he was dead, they wanted to say he did it.”

Detectives pressed Kevin Brown to confess to 1984 sexual assault and killing.

Kevin Brown had been implicated in Claire Hough’s killing by a new round of forensic testing in 2012. He’d worked in the police lab when the case was first investigated and believed inadvertent contamination explained how his sperm cells wound up on vaginal swabs collected during the girl’s autopsy. Detectives didn’t.

Police weren’t the only ones Rebecca Brown lashed out at after her husband’s body was found hanging from a tree in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park. She sent an email to her sister, one of several relatives who had made it clear to Kevin Brown that they thought he was somehow involved in the teen’s death.

“He couldn’t bear the thought of being locked up, and your words sent him over the edge,” Brown wrote. “Don’t you see how you added to his fragile state? ... It all added up to be too much for him. And now he is gone forever. Oh, my God.”

God is a big deal to Brown, a devout Catholic. After her husband died, in keeping with ancient traditions, she had a Mass celebrated for him for 30 straight days, believing it would free his soul from purgatory. She went to the tree where he died, said a prayer, picked up leaves from the ground and put them in his Bible.

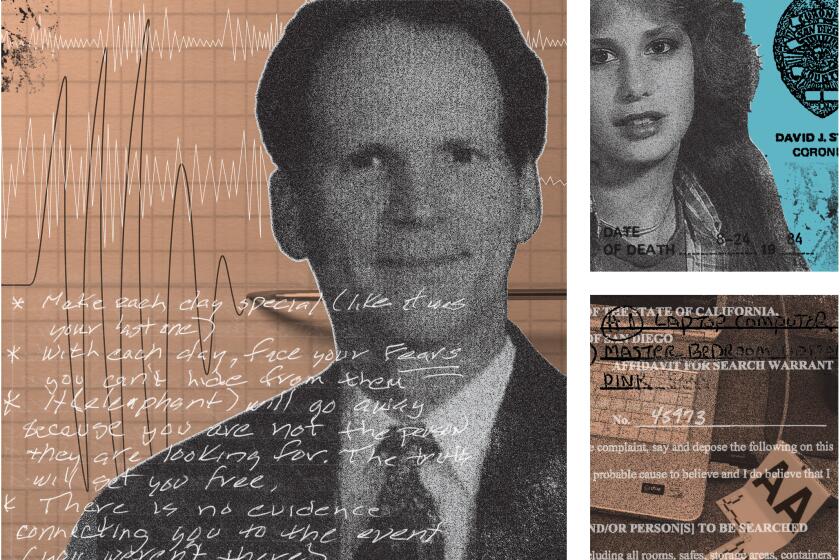

When her spiritual adviser, Msgr. Richard Duncanson, came to visit, she learned something that added to her anger. After her husband died, the priest was interviewed by Det. Michael Lambert, lead investigator in the Hough murder, who wanted to know whether Kevin Brown had ever confessed to the crime.

Duncanson was upset by the request — he told her no police officer had ever asked him to breach the confidentiality of the confessional in 45 years as a priest — and he refused to disclose what Brown said.

But he was willing to tell Lambert this: Brown never confessed to sexually assaulting or murdering anyone, or to having sex with a minor.

- Share via

Detective Michael Lambert discusses his attempted interview with Kevin Brown’s priest.

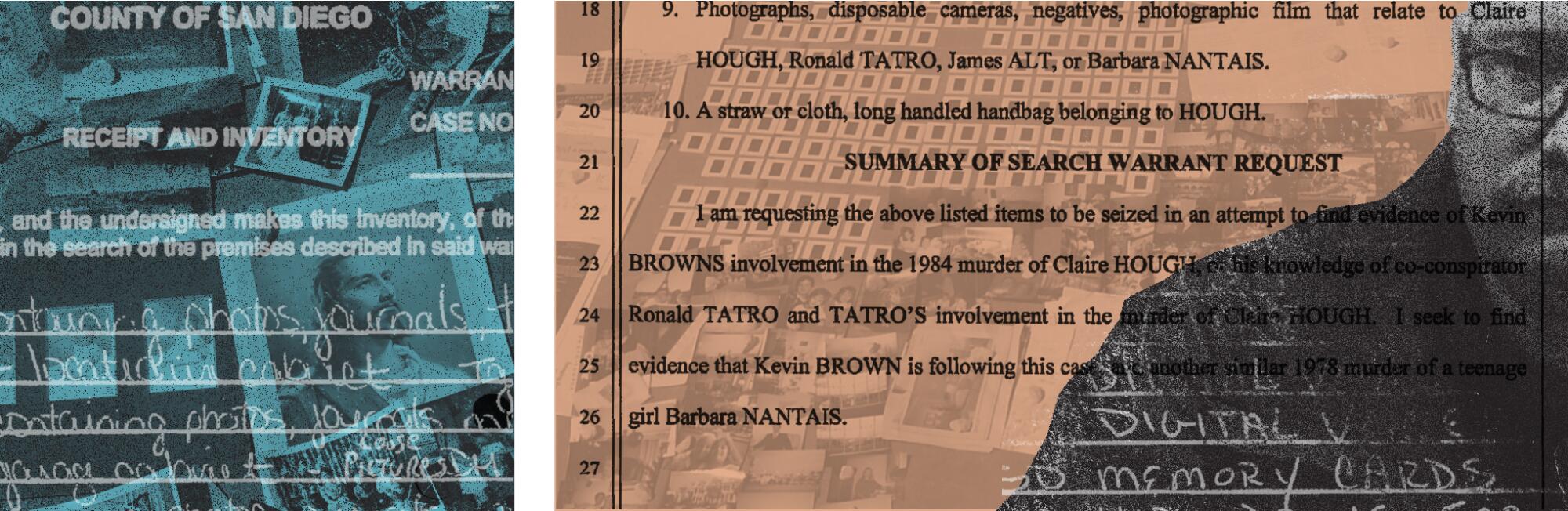

Rebecca Brown also learned that investigators obtained a search warrant for a cabin in Julian that her family owns, not far from where Kevin Brown killed himself. He’d gone there shortly beforehand.

Police searched the house for anything that might connect him to the Hough case, a suicide note maybe. They found nothing.

Rebecca Brown, meanwhile, found a purpose. “They are not going to get away with this,” she said.

No apologies

Suing police officers is an uphill battle. It’s hard to get past the courthouse door because of legal precedents that give officers qualified immunity, even when there is wrongdoing. And it’s hard to sway juries, who are often sympathetic to police because of the importance of the job and its inherent dangers.

Brown was told as much by Eugene Iredale, a San Diego attorney she consulted about filing a lawsuit. He also played devil’s advocate. Don’t you think police should have investigated your husband after the DNA came back? If it was your daughter who had been murdered, wouldn’t you want justice?

But Iredale thought she had a winnable case, and he took it on.

Educated at Columbia University and Harvard Law School, Iredale has been an attorney for almost 40 years, specializing in criminal defense and civil rights cases. He has tried more than 200 cases to verdicts in state and federal courts and has twice participated in oral arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Bearded and often bemused, self-deprecating and quick with a quip, Iredale is respected in local legal circles for his courtroom skills. His closing arguments sometimes draw spectators.

On Dec. 17, 2014, a claim was filed against the city of San Diego, a required precursor to a lawsuit. Lodged on behalf of Rebecca Brown and her husband’s estate, it accused detectives of illegal search and seizure, investigative misconduct and wrongful death.

The city could have settled. Brown said she would have been satisfied with an apology and enough money to cover her legal costs. She got neither.

Seven months later, a 67-page suit was filed in federal court. It named Lambert as the main defendant and said he had botched the investigation, ignoring both the possibility of contamination in the lab and Kevin Brown’s fragile mental state.

Zimmerman, the police chief, responded with a statement praising her team for solving the case. “The Claire Hough murder investigation is an example of the San Diego Police Department’s relentless pursuit to hold murderers accountable for their actions no matter how much time has passed,” she said.

In the City Attorney’s Office, the case was assigned to Catherine Richardson, a litigator with more than 30 years of trial experience. Born in the Bronx, raised on Long Island, she went to the other coast for college, earning a bachelor’s degree at UC San Diego and a law degree at the University of San Diego.

Her proudest moment as an attorney, she once told San Diego Lawyer magazine, came when she was in private practice. She filed suit and won a six-figure verdict for a female pedestrian hit by a car. “It was extremely rewarding to have been able to provide a measure of justice to my client and to show her that the system does work,” Richardson said.

Her defense in the Brown lawsuit was built around the idea that police had to investigate the former criminalist, lest they be accused of protecting their own, and that Lambert went where the evidence led him.

She said in her court papers that whatever pressures drove Brown to kill himself came mostly from his own actions and those of family members who thought he might be guilty.

A lab on trial

Pretrial wrangling went on for almost five years — depositions, motions to exclude evidence, rulings on qualified immunity — before potential jurors filed into the San Diego courtroom of U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw on Feb. 3, 2020.

By then, the case had been narrowed to a handful of constitutional claims for relief. Three alleged violations of the 4th Amendment’s protections against unreasonable search and seizure. Another sought compensation under the 14th Amendment for the loss of love and companionship suffered by Rebecca Brown.

Sabraw is an 18-year veteran of the federal bench. His American father and Japanese mother gave him the middle name Makato, which translates to “truth.” He made national headlines in 2018 when he ordered the U.S. government to stop separating families caught trying to cross the border.

Although he is married to Summer Stephan, the county’s district attorney, Sabraw has a reputation for fairness to both sides of the aisle. Soft-spoken but forceful, he runs a tight ship. He set aside two weeks for the Brown trial and kept the attorneys on a running clock. He also instructed them to stay behind the lectern while presenting their cases.

That was a challenge for the animated Iredale, who likes to wander. Less so for Richardson, who is lower key and almost professorial, reading glasses perched at the end of her nose or on top of her head.

As the trial opened, Iredale set out to paint a picture of the San Diego Police Department as one that didn’t want to admit it accidentally contaminated evidence in the Hough case, did a reckless investigation, and bullied Kevin Brown into killing himself.

He went first after the public perception, created through television shows like “CSI,” that police labs are pristine places of white-coated, hair-netted perfection. Witness after witness acknowledged that contamination happens in even the best facilities, and no reputable forensic scientist would claim otherwise.

But Richardson also made this point repeatedly: None of the witnesses had ever heard of a case in which the contamination involved a lab worker’s sperm on vaginal swabs.

So that was another hurdle for Iredale. He had to show how it might have happened, which meant talking about criminalists bringing into the lab their own semen.

“Forgive me for the grossness of what I have to say,” Iredale told the jury.

James Stam, who retired in 2008 after 30 years in the SDPD lab, testified that analysts need to make sure chemicals are working properly before they examine evidence for the presence of sperm. They cut out a piece of cloth with semen on it, put it in a vial, and add the chemicals to see if the solution turns the right color.

Labs could buy semen standards from outside vendors, but those supplies are limited and expensive, he said. So analysts bring in their own. And if they run out, they borrow from each other.

Under cross-examination by Richardson, Stam said he had no proof that Kevin Brown brought his own sperm into the lab. No logs were kept documenting the practice. But everybody did it, he said.

He also acknowledged that he wasn’t in the room when the Claire Hough evidence was examined in 1984 — by then he was a supervisor, working on a different floor — so he didn’t know exactly what might have happened.

But somebody else did.

Breathtaking shift

John Simms looked haunted as he walked to the witness stand.

The retired criminalist was the one who first worked the Hough murder. He had no recollection of the testing. Thirty-six years and lots of cases had gone by since then.

After Kevin Brown’s DNA was found on the vaginal swabs in 2012, Simms was “mortified” to learn that he had been the original analyst and that he might accidentally have done something to contaminate the evidence. He initially told his bosses he didn’t think he would have made such a mistake.

Now he wasn’t so sure.

Responding to questions from Iredale, Simms said the crime lab in 1984 didn’t know yet about DNA testing and didn’t have the safeguards in place today to prevent contamination. The analysts worked at large tables in the same room. They cleaned their tools with water or alcohol, not bleach, which is used now.

Analysts kept their semen standards in small envelopes in a refrigerator in the lab, he said. He couldn’t remember if or how they were labeled, or if they were kept separate from each other in any particular way.

Then he offered this possible scenario:

When he was preparing to examine the Hough evidence, he went to the refrigerator and grabbed what turned out to be Kevin Brown’s semen standard. He cut out a piece of it to check the testing chemicals. He cleaned his scissors, but not enough to remove all the sperm cells, and used them again to snip the vaginal swabs for analysis.

It was a remarkable, fall-on-your-sword moment in the courtroom, a breathtaking shift from a vague theory about contamination to a blow-by-blow description. The jurors seemed riveted, several of them writing furiously in their notebooks.

Richardson tried to walk back the testimony. She pointed to a sworn deposition and a signed declaration Simms had given three years earlier that said it was his usual practice to use his own semen standard, and that he was careful with his tools while working a case — scissors to cut the semen standard and a scalpel on whatever evidence he was analyzing.

Now Simms said he could no longer be certain what he did. He couldn’t recall if he ever borrowed someone else’s semen standard, but they were available for “general use” in the refrigerator, so he might have.

His 1984 notes from the Hough case don’t say whose standard he used. Nobody thought to write down that kind of information back then. It was a different world, pre-DNA.

But Simms also couldn’t point to any other case in his career in which he fouled evidence in the manner he was now suggesting.

That led Richardson to ask, “So when we went through the scenario of how you might have contaminated the Claire Hough vaginal swabs with Kevin Brown’s DNA, you don’t believe that you did that?”

Simms replied, “I want to believe that I didn’t make a mistake, but I have to admit that it is possible.”

A cookbook, a Bible, Ronald Reagan

In courtroom comments to the judge, outside the presence of the jury, Richardson and her colleague Erin Kilcoyne brought up what they saw as a “dramatic” change in Simms’ story.

They suggested he had done it because Kevin Brown was a friend. They also knew Simms had been talking to other criminalists who were in the lab back in the 1980s, some of whom were upset that their DNA profiles — supposedly in the database to be used only in case of contamination — were being looked at in murder investigations.

Richardson tried to shift the jury’s focus away from whether contamination happened to whether Lambert knew it was possible. That proved a difficult line to walk.

Now retired after 28 years with the department, Lambert was on the stand for parts of three days, called first by Iredale as he presented his case and then by Richardson as she built hers.

He testified that he was new to the cold-case team when Sgt. Frank Hoerman assigned him the Hough murder. By then, the DNA results had come back, and he was told that crime lab managers had ruled out contamination. (Hoerman got on the stand and verified that’s what he’d said.)

But several lab managers testified that they weren’t there in 1984 and that they told Hoerman and Lambert to talk to the criminalists who were if they wanted to know what went on back then.

Lambert did talk to some of the analysts, but he was mostly focused on stories about Kevin Brown’s interest in nude photography and porn movies. He never interviewed Simms.

He never interviewed Jennifer Shen, either, who was lab manager as he began his investigation, even though he quoted her in a search-warrant affidavit as saying contamination “is not possible” — an assertion she denied when she took the stand.

The affidavit loomed large during the trial. It had convinced a judge to approve the search, which brought detectives to Kevin Brown’s door in the first place, and then to everything that happened after.

Iredale peppered Lambert with questions about information he omitted from the affidavit — facts that would have been favorable to Brown and might have led the judge who authorized the warrant to wonder about probable cause.

Chief among them: that criminalists had their own semen in the lab.

Lambert said he didn’t learn that until late in his investigation, about a month before Brown killed himself. He heard about it from some of Brown’s relatives and didn’t believe it was true until he called a lab employee, who confirmed the practice. (The lab employee also testified and said Lambert appeared shocked by the news.)

Iredale pointed to numerous interviews Lambert did and never wrote reports about, suggesting the detective had blinders on regarding contamination because he had made up his mind that Brown was guilty and was intent on getting a confession.

The attorney brought up statements the detective made to police colleagues about “sweating” Brown and tipping him over emotionally by showing him photos of the murder victim. He accused Lambert of feeding Brown’s relatives damaging and misleading information that he knew would make it to the suspect’s ears.

“The fact of the matter is,” Iredale said, “that you deliberately wanted to put pressure on Kevin Brown, psychological pressure, because you wanted to see if you could crack him, did you not?”

“No, sir, that is not the case,” Lambert said.

Iredale zeroed in on what the lawsuit alleged was a major source of pressure: the seizure of thousands of items from the Brown home, all but a handful not authorized by the warrant, and Lambert’s refusal to return them, even after he found nothing of evidentiary value.

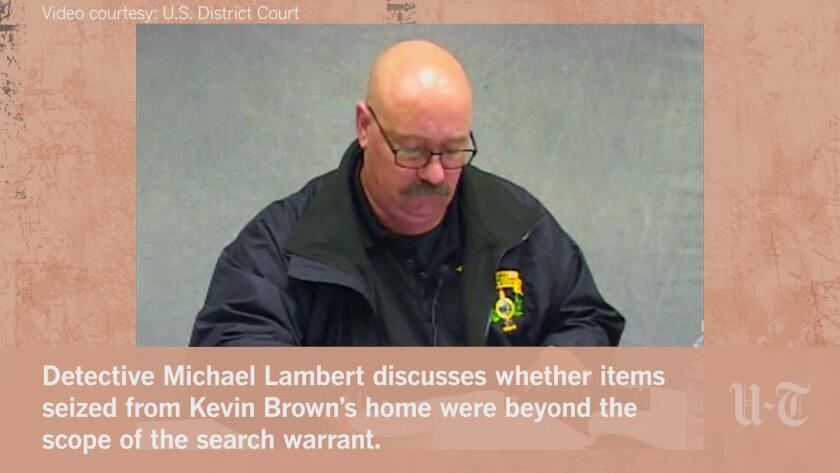

- Share via

Detective Michael Lambert discusses whether items seized from Kevin Brown’s home were beyond the scope of the search warrant.

A psychologist who had testified earlier said that was a “substantial factor” in Brown’s suicide because he equated the continued seizure as an indication that he might be arrested and jailed.

One by one, the lawyer showed Lambert 50 photos of items taken in the search. First up was a painting of the Virgin Mary. “Did you think that that in some way was evidence of a crime, sir, that required you to keep this until the death of Kevin Brown before you gave it back?”

“No,” Lambert said.

This went on for more than 15 minutes. A cookbook. Old photo albums. A Bible. A newspaper clipping about baseball slugger Roger Maris. A brochure from a Royal Caribbean cruise. A photograph of Ronald Reagan. A songbook. A Halloween mask.

“They were not evidence in the case,” Lambert admitted.

Iredale asked him about the news release the Police Department issued after Brown died. It claimed “preparations were being made” to arrest him.

Lambert said that was incorrect. “It had been discussed, but we hadn’t made formal plans to go out on a particular day and go arrest him,” he said. “We weren’t there.”

When it was her turn, Richardson took Lambert through his role in the search of the Browns’ home. Although he wrote the warrant that convinced a judge to approve the search, he wasn’t there when the items were seized. He said he didn’t know what was in the boxes until he examined them later.

As for holding on to the items, Lambert said he was waiting for the District Attorney’s Office to decide whether Brown would be charged — and that if the Browns were so desperate to get them back, they could have gone to court and asked a judge to order it.

He also denied misleading anyone in the affidavit, or in his interviews with Brown’s relatives, and said he had nothing to do with the posthumous news release about the former criminalist.

“At the time the press release was issued,” Richardson asked, “did you believe that Kevin Brown had involvement in Claire Hough’s murder?”

“I did,” Lambert said.

‘I used to trust everyone’

Rebecca Brown took the stand to tell the jury about her life with Kevin Brown.

Julia Yoo, Iredale’s partner, did the questioning. She displayed a series of photos of the couple throughout their marriage.

“He was so gentle, and kind, and humble,” Brown said. “Rather not like other people I had been with.”

She said he spoiled her, took care of chores around the house, greeted her at the end of work days with a glass of wine.

She wasn’t alarmed when cold-case detectives first came to the house, asking to talk to her husband about an old murder. It had happened before, she said. She sat in on the interview for a while, and then went to her high school teaching job.

In the afternoon, the detectives called her out of the classroom to tell her they were searching the house.

Things went downhill from there, she said, detailing the escalating tension in the house as the items police took were not returned. That upset her 80-year-old mother, who lived in the home with the couple and cried about not being able to look at photographs and other mementos.

“This was her life,” Brown said.

Her husband’s mental health deteriorated, too, as the investigation continued, she said. He wasn’t sleeping. His hands shook. He was distracted. He drove into a parked car, hit a bus.

Her health was affected as well. Her skin broke out in several places, infections that required antibiotics.

She detailed her husband’s final weeks, his disappearance, the discovery of his body.

Brown went back to work a month later, to finish the school year. She taught another year, but then retired, earlier than planned. “It was too difficult to keep going into work every day,” she said.

People there knew about her husband and assumed he was guilty, she said. The U.S. government classes she taught had lost their meaning. “I didn’t believe [the system] was effective and working in this country anymore, and I couldn’t teach it,” she said.

She sought help from therapists and grief counselors. She tried dating. But she was still angry. “I used to trust everyone,” she said.

Yoo asked, “What do you miss most about Kevin?”

“I miss having someone who was in my court and I was in their court, and we were able to spend our days, and planning a future and a life with. Just someone who was kind and I could trust and I could love, and they could do the same back for me.”

“And in those 21 years of marriage, was Kevin Brown there for you every night?”

“He was there for me every night.”

“Who sleeps next to you now?”

“My cat and my teddy bear.”

Cross-examination

Richardson started her cross-examination by asking questions designed to show that there was already stress in the Brown household before the police investigation started, stress related to Rebecca’s mother and brother moving in with them.

She also went through problems Kevin Brown had with anxiety and other mental-health issues that predated the detectives knocking on his door.

Then she tried to upend the characterization of the Browns as a loving couple who shared the same bed every night. She displayed a series of photos taken during the police search that were of the closet in the master bedroom. The photos showed a makeshift nightstand, a cross on the wall, pillows, an iPad, a lamp and a clock radio.

“At the time of the search,” Richardson asked, “you were actually sleeping in your closet, weren’t you?”

Brown denied that. Because of her husband’s insomnia, he wanted lights out by 10 p.m., so she made a “makeshift cozy spot” where she could grade school papers, watch movies and pray her rosary without disturbing him, she said.

Richardson turned to the search and challenged the idea that the Browns were harmed by police holding onto their possessions. (She later called a psychologist who also downplayed the search as a source of the couple’s torment.)

“Are you claiming that you were damaged because for 10 months you couldn’t go into the garage and look at your baby outfit?” Richardson asked.

“I didn’t have access to anything that had been taken, that had no right to be taken, that was mine,” Brown said.

“Are you claiming that you were damaged because for 10 months you couldn’t go and look at your copy of the Declaration of Independence?”

“It was mine,” Brown said.

In a similar vein, to challenge the lawsuit’s allegations that Lambert had been reckless about contamination and Kevin Brown’s mental health, Richardson asked several questions regarding information the couple never shared with the detective. They didn’t tell him Kevin Brown had his own sperm in the crime lab, for example.

“I assumed he knew it,” Brown shot back. “He is an investigator.”

Richardson displayed a copy of the email Rebecca Brown sent her sister after the suicide, a note that accused various unsupportive relatives and “the police investigation itself” of pushing him over the edge. It doesn’t mention Lambert by name or the items seized during the search.

“I was blaming everyone, and myself,” Brown said. “I wasn’t writing a legal document here.”

‘What is it worth?’

The courtroom was packed for closing arguments.

Iredale spoke for almost 90 minutes. He started out highlighting the Constitution and its 4th Amendment protections against unreasonable search and seizure.

“In our country, the reason why we hope and believe that we are exceptional as a country and as a people is because we live our constitutional values,” he said. “Because the Constitution, if it is to exist, must exist in the hearts and the minds and the lives of the people of the United States.”

The attorney criticized what he called Lambert’s “course of conduct that was deliberately designed, over time, to bully, to intimidate, and ultimately to drive Kevin to what he thought he wanted, which was a confession. But when a man is innocent, but so frightened, you don’t get a confession — you get a suicide.”

He suggested the jury award Rebecca Brown between $3 million and $4 million, and another $8 million for her husband’s estate.

“What is it worth?” Iredale asked. “What is it worth to be alone, and you had somebody you loved for 21 years and they could be with you, but they aren’t?

“What is a kiss worth? What is a song worth? What is a smile worth? You decide.”

Richardson, who spoke for more than an hour, started her closing argument by talking about the murder victim.

“Hopefully what is not lost in all of this is the fact that a 14-year-old girl, Claire Hough, was sexually assaulted, mutilated and murdered,” she said. “And that the goal of Detective Lambert, and all of the police detectives who investigated her murder, and the lab personnel, was to get some measure of justice and closure for the Hough family, and to bring the perpetrator or perpetrators to justice.”

She said Lambert “had no preconceived notions” during his investigation, which led him to lab workers who talked about “Kinky Kevin,” and to the suspect himself, who made incriminating statements in interviews with detectives.

“What are the detectives supposed to do if not to investigate?” Richardson said. “Mr. Brown is giving them the material for them to investigate. So that’s what they did.”

She made her own suggestion about monetary damages. Sabraw had ruled before the trial started that Lambert had violated the Browns’ constitutional rights by seizing items beyond the scope of the warrant, and it was up to the jury to decide how much the harm was worth.

Richardson suggested $2.

‘How did you not know?’

The jury arrived the next morning ready to begin deliberations, but there was a problem.

The City Attorney’s Office had sent in the wrong evidence exhibits. Instead of providing selected snippets of the police interviews with Kevin Brown that had been talked about during the trial, it submitted the entire transcripts — and the transcripts included mentions of a lie-detector test, information not allowed to come in.

Iredale asked for a mistrial. “If it was done deliberately, it is outrageous,” he told Sabraw. “Inadmissible evidence of a highly prejudicial kind was placed before the jury.”

The thumb drive with the transcripts was pulled from the jury room. Apparently only one exhibit had been viewed, and it didn’t involve the interviews. Sabraw denied the motion for a mistrial. Richardson blamed it all on a misunderstanding and haste.

The problem took three hours to sort out. Jurors sent word that they were not happy. Neither was the judge. “This is the first trial where this has happened, and I just don’t understand it,” he said. “I have had well over 300 jury trials. I have never had this experience.”

Once the correct exhibits went in to the jurors, they took less than four hours to reach a verdict.

They ruled that constitutional violations by Lambert related to the search harmed the Browns to the tune of $3 million. And that Lambert’s “deliberate indifference” had caused the loss of society and companionship to Rebecca Brown, and that was worth another $3 million.

Rebecca Brown put her head in her hands and sobbed briefly. Lambert wiped at his eyes with a paper napkin.

Jurors, it turned out, had taken to heart Richardson’s repeated statement that the heart of the case was what Lambert knew as he did his investigation. During their deliberations, they focused on his claim that he didn’t learn about criminalists having their own sperm in the lab until shortly before Kevin Brown killed himself.

“How,” juror William Fleck said to reporters afterward, “did you not know?”

The jury also found that Lambert had acted with “malice, oppression or in reckless disregard” of the Browns’ rights, which set the stage for a hearing on punitive damages. It was held four days later.

Lambert was the only witness. He described the jury verdict as “a gut punch” and said, “I spent a good portion of my life in law enforcement, and I have never had my integrity questioned before. Let’s be honest — I am a prideful person, and I think most people are, and this certainly damaged my pride.

“I fear that it is forever going to hurt my reputation as a cop, because I worked very hard in this profession. And so that’s the biggest thing for me.”

Iredale asked him whether he thought he had done anything wrong during the investigation. “I believed what I was doing was correct,” Lambert said.

That didn’t sit well with the attorney.

“I wanted to be prepared to come here today with a spirit of generosity and to say that in order to ask for justice, as I did, I must be prepared to render justice, and that in considering the appropriate punitive damage, you may consider not only the bad but the good,” Iredale told the jury. “[Lambert’s] testimony makes me hesitate in making that request of you, because he has learned nothing.

“What he learned from this case is not the lesson that should have been imparted: I did wrong, and my wrong has caused a terrible harm that caused one person to lose their life, and one person to lose almost all the joy in that life for six years.”

Richardson countered that Lambert got the jury’s message and respected it. “No punitive damage award is going to punish him more than the verdict that you rendered, because that verdict told him that you believe his actions caused Mr. Brown’s death,” she said. “You don’t need to punish him further because that’s something he will live with for the rest of his life.”

Jurors began deliberating and sent the judge three questions that indicated they didn’t want to hit Lambert too hard.

They wanted to know whether the $6 million verdict they’d delivered earlier would be paid by the city. They wanted to know whether Lambert would be on the hook personally for any punitive damages. And they wanted to know whether they could recommend community service instead of a monetary award.

“Common-sense questions,” Sabraw said to the attorneys, but also a minefield. If the jurors knew that Lambert was indemnified for the $6 million — which he was — would they be more willing to hammer him on punitive damages? If they thought he had to pay the $6 million himself, would they go easy?

Sabraw sent back this answer: “The verdict has been rendered. This issue is therefore not before you.”

He told them that Lambert would be liable for the punitive damages, which was technically true. (The City Council could also vote to cover those costs.)

Community service? No.

The jury deliberated for another 40 minutes and came back with this: $50,000.

Finally at peace

On a crisp autumn day last year, Rebecca Brown went to her husband’s gravesite. She placed a pink rose on the marker, snipped from a bush in the yard at home. Her husband used to take care of the roses.

The marker has her name on it next to his. It’s where she’ll go, too, when it’s time.

In the center is an engraving of a Claddagh ring, the traditional Irish design that denotes love, friendship, loyalty. That last one means a lot to Rebecca Brown, which is why for more than five years it was too hard for her to visit the grave, she said. There was unfinished business.

Vindicated by the jury’s verdicts, she said she feels more at peace at the cemetery now.

“Unless I could make people understand what happened, Kevin’s soul couldn’t rest,” she told the Union-Tribune. “Now it can.”

Brown received a check with two commas in it from the city in May. It came after a round of motions and appeals by the city, and then mediation. The final agreement shaved off part of the financial compensation.

It was never about the money, she said. She split the proceeds in half with her attorney and has started giving away some of her share. She’s created a theater scholarship at the high school where she used to work. She’s donated to the blood bank, the humane society, her church.

She said she got an education in human nature she never wanted, one that’s left her more skeptical of law enforcement and government in general. She no longer reads “DNA evidence” or “confession” in a news report and thinks “end of story.”

Some people, Brown knows, still think her husband had something to do with what happened to Claire Hough on that August night in 1984. She’s stopped hoping for apologies or admissions of wrongdoing.

She also knows that actions can speak louder than words.

In the wake of the Kevin Brown investigation, the police crime lab changed its procedures. Criminalists no longer use their own semen for testing.

Editor’s note: This story was compiled from thousands of pages of police reports, court filings, sworn depositions and trial transcripts. Unless otherwise noted, the quotes used are from those records.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.