Column: America loves rap, not Black people. Don’t be fooled because this bill protects lyrics

- Share via

The first time Erik Nielson testified in the trial of an aspiring rapper, it was nearly a decade ago in Ventura County.

An Ojai Valley teen named Alex Medina had been charged with first-degree murder as an adult with gang enhancements over a stabbing at a house party. In hopes of winning a conviction, prosecutors had introduced some of Medina’s lyrics as a key part of their evidence, arguing that the words should be treated not at as creative expressions, but as “journals” of his real-life “gangsta” behavior.

It was up to Nielson, then an unknown academic expert from Virginia who grew up as “one of those suburban white kids who loved rap music,” to push back.

“Rap lyrics,” he testified at the time, “are so unreliable that it’s very difficult to tease out what might be real and what might not be.”

Obvious, right?

Well, Medina got convicted anyway. And in the years since then, dozens of other rappers all over the country have had their lyrics used against them, too, with prosecutors and cops mining old songs and videos in search of supposed proof of gang activity.

Through it all, many in the upper echelons of the recording industry have said and done nothing, apparently preferring to pretend that Black and Latino men aren’t getting thrown in prison for making music.

That is, until now.

Awaiting Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature is Assembly Bill 2799, which would make California the first state to restrict how forms of creative expression, from music to books, can be used as evidence in criminal proceedings. The state Legislature passed it unanimously.

Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer, the Los Angeles Democrat who authored AB 2799, said he was unaware how many men of color, particularly Black men, were being prosecuted with their lyrics before the recording industry approached him. And then he was appalled.

“They were the first ones to really kind of enlighten me,” Jones-Sawyer confessed.

Nielson isn’t at all surprised. The recording industry has a reason to talk about such things now, particularly with lawmakers at the state and federal levels.

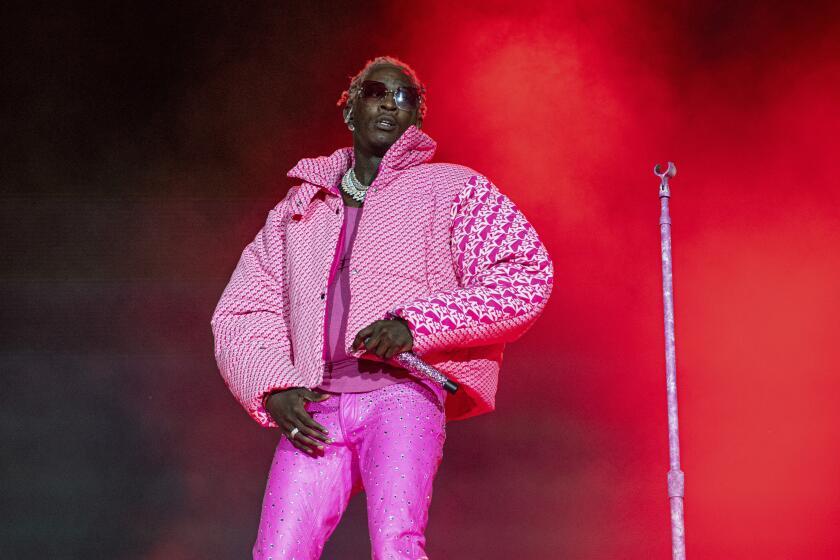

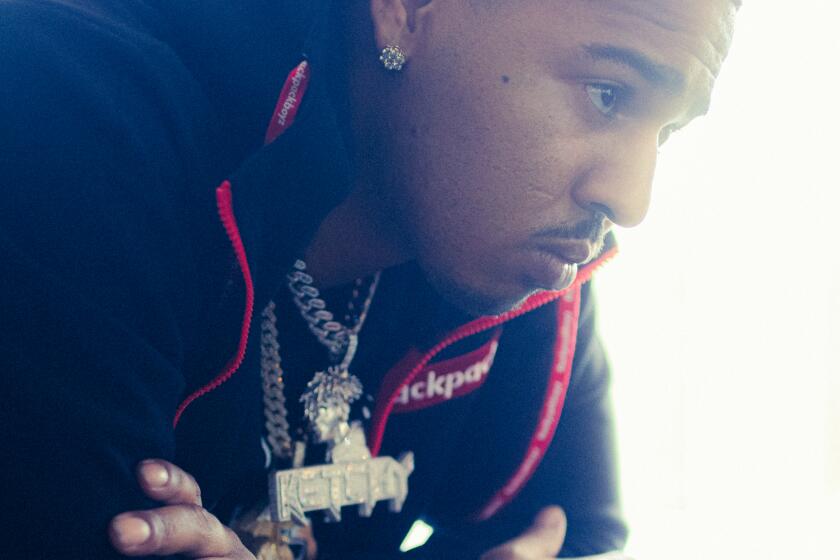

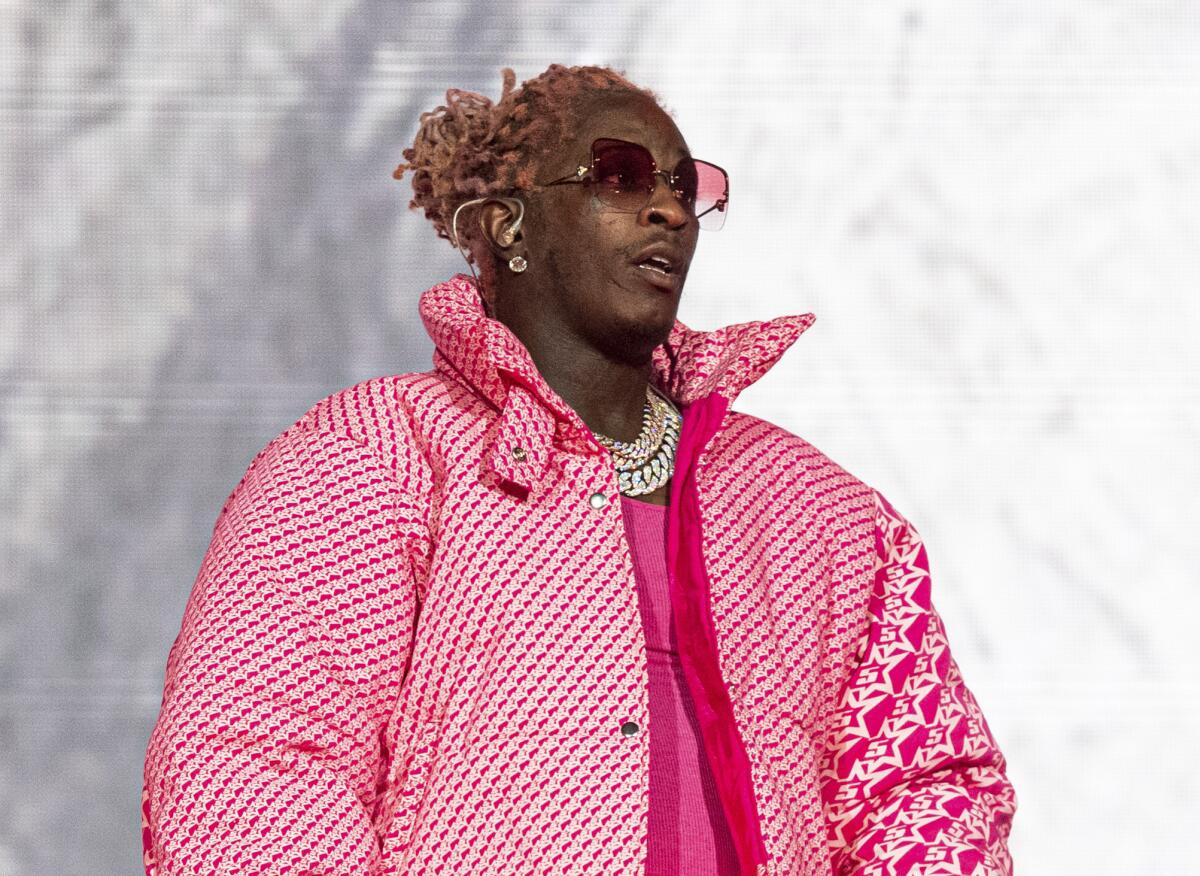

Two of rap’s biggest stars, platinum-selling rapper Young Thug and his chart-topping protege Gunna, are facing gang-related racketeering charges in Georgia, with their lyrics and music videos being used as evidence. Both have been in jail for months.

Rapper Young Thug, who is accused of conspiracy to violate Georgia’s RICO Act and participation in a criminal street gang, is facing six new felony charges.

“We’ve wanted to see more advocacy from the recording industry for years, but it’s only once it’s clearly going to hit the bottom line,” Nielson lamented. “Somebody like Young Thug made it real because this is normally a practice that targets aspiring artists and amateurs, not somebody with his profile or his resources.”

Many people will remember the pearl clutching over N.W.A‘s “F— Tha Police” in the 1980s and over just about every album put out by 2 Live Crew.

Gen Xers, in particular — and millennials who wish they were Gen Xers after the last Super Bowl halftime show — will remember when a prosecutor weirdly referenced lyrics from “Murder Was the Case” during Snoop Dogg’s 1993 murder trial.

“Murder is the crime they committed,” then-Deputy Dist. Atty. Robert Grace told jurors with a straight face.

Well, things have gone way beyond pearl clutching and weird.

Since testifying in Ventura County, Nielson says he has worked on roughly 100 cases in which lyrics have been used as evidence in criminal proceedings, including 15 that he expects to head to court in the near future.

The associate professor at the University of Richmond has become the go-to national consultant. All told, he and fellow researcher Andrea L. Dennis have identified more than 500 such cases on the books since 1991.

“I can certainly say my workload has increased exponentially,” he told me.

When prosecutors were hounding the late Los Angeles rapper Drakeo the Ruler, zeroing in on his lyrics, it was Nielson who connected his family to defense attorney John Hamasaki. And it was Hamasaki who managed to secure a plea deal on a lesser charge and win his release.

It was just the latest in series of cases in which he represented rappers.

The first was in 2014, when Hamasaki was an attorney for Laz Tha Boy, a Bay Area rapper who had been charged in two gang-related shootings, even though the main evidence of his gang association were lyrics and rap videos.

“It dirties up a case. It brings in more otherwise inadmissible information,” said Hamasaki, who is now running for San Francisco district attorney. “The biggest problem is it’s taking an artistic outlet and using that to criminalize somebody and not recognizing that, hey, just because somebody’s talking about having a gun doesn’t mean they have a gun and did a shooting.”

But there’s an obvious reason why so many prosecutors refuse to separate fictional storytelling from real-life fact. It’s because the shameless tactic too often works with juries.

Nielson can rattle off cases involving rap lyrics in which convictions were handed down, even when there was no other credible evidence.

In a study conducted in the 1990s, researchers presented violent lyrics from a country song to two groups of people. The first group was told they came from a rap song. The second group was told the lyrics came from a country song.

“The group who thought that this was a rap song thought it sounded far more threatening and in need of regulation than the same lyrics that were characterized as country,” Nielson said. “That study was actually duplicated in 2016. Same findings.”

This is telling since rap has evolved since the early days of N.W.A and become a massively profitable genre of music that is supposedly loved, accepted and celebrated by Americans of all races and ethnicities. Rap may be mainstream, but juries, taking the lead from prosecutors, prove that racism is too.

In California, at least, we have the Racial Justice Act, which prohibits the use of race and ethnicity in criminal proceedings, including in cases against rappers. It also allows people who have been convicted recently to challenge and potentially overturn or reduce their sentences if they can prove bias.

Still, it’s incredibly important for Newsom to sign AB 2799 into law. It will ensure that prosecutors in California will be forced to meet even tougher conditions, such as proving in a pretrial hearing how a certain song or film is relevant and contains incriminating evidence about the case at hand.

As Jones-Sawyer told me, “the judicial system needs to be fair.”

Live Nation has been repeatedly accused of failing to follow industry protocols for keeping concertgoers and performers safe, according to a Times review.

This is also why it’s important for lawmakers in New York to pass a now-stalled bill that would prohibit “prosecutors from using creative expression as criminal evidence against a person without clear and convincing proof that there is a literal, factual nexus.”

Nielson has been deeply involved in that effort, much of it growing out of a policy suggestion in his 2018 book, “Rap on Trial.” In January, a constellation of rap stars, including Jay-Z, Meek Mill, Yo Gotti, Big Sean and Killer Mike, joined him in signing a letter encouraging lawmakers to pass it.

There are some concerns that New York’s legislation — also backed by the recording industry — is tougher than California’s AB 2799, particularly because the latter is identical to legislation Congress is considering. Nevertheless, this is a case in which something is better than nothing.

“I do think that there was some pride that New York, the home of hip hop, was also going to be the first state to pass this protecting it,” Nielson said. “And so now that California has stolen some of their thunder, I hope that there is some sense that this isn’t actually a radical proposal.”

This is the kind of East Coast-West Coast rap rivalry we need.

Not just for the Young Thugs and the Gunnas, the rappers who have made it. It’s for the rappers who haven’t.

Remember that when you hear about the Los Angeles and San Francisco chapters of the Recording Academy urging Newsom to sign AB 2799, so that “all artists are able to express themselves freely without fear of reprisal” from the criminal justice system.

Not just those who make millions of dollars for the recording industry.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.